Ulrike Leitner

Die mehr als 450 Briefe umfassende, in Buchform edierte Korrespondenz Alexander von Humboldts mit seiner Nichte Gabriele von Bülow (darunter viele Erstveröffentlichungen) spiegeln das letzte Drittel im Leben Humboldts, seine wissenschaftliche Arbeit und Publikationen, öffentliches Wirken am preußischen Königshof und in den Akademien der Wissenschaften und Künste, Reisen nach Paris und Pendeln zwischen Berlin und Potsdam – ein geselliges Leben in Freundes- und Familienkreis wider. Die Briefe (fast ausschließlich von Humboldt, nur wenige von Gabriele) nehmen wegen ihrer familiären Nähe eine Sonderstellung unter den zahlreichen Briefwechseln des Gelehrten ein. Humboldt versorgt seine Nichte mit den neuesten Nachrichten vom Hof, aus dem Bekanntenkreis, dem politischen Leben und Gabriele nimmt regen Anteil an seinen Arbeiten.

Alexander von Humboldt’s correspondence with his niece Gabriele von Bülow, published in a book, comprising more than 450 letters (including many first publications), reflects the last third of Humboldt’s life, his scholarly work and publications, public activities at the Prussian Royal Court and in the Academies of Sciences and Arts, trips to Paris and commuting between Berlin and Potsdam – a sociable life among friends and family. The letters (almost exclusively from Humboldt, with only a few from Gabriele) occupy a special position among the scholar’s numerous correspondences because of their familial nature. Humboldt provides his niece with the latest news from Court, his circle of acquaintances and political life, and Gabriele takes a lively interest in his work.

La correspondencia de Alexander von Humboldt con su sobrina Gabriele von Bülow, que comprende más de 450 cartas (incluidas muchas publicadas por primera vez) y ha editado en forma de libro, refleja el último tercio de la vida de Humboldt, su trabajo científico y sus publicaciones, su trabajo público en la corte real prusiana y en las academias de ciencias y artes, los viajes a París y las mudanzas entre Berlín y Potsdam, una vida social con amigos y familiares. Las cartas (casi exclusivamente de Humboldt, y con solo unas pocas de Gabriele) ocupan un lugar especial entre las numerosas correspondencias debido a su proximidad familiar. Humboldt comunica a su sobrina las últimas noticias de la corte, de su círculo de conocidos, de su vida política, y Gabriele participa activamente en su trabajo.

The German Literature Archive (Deutsches Literaturarchiv Marbach/Schiller Nationalmuseum – DLA/SNM) holds a treasure, of which only a small part has been unearthed: the Humboldt family archive. Alexander von Humboldt’s letters to Gabriele von Bülow, many published for the first time, not only demonstrate his sympathy and care for his niece and her family, the kindness of his character, as Gabriele said, but they also reflect Humboldt’s activities in the last third of his life in Berlin as well as his political views and judgments about people, particularly unvarnished due to their private nature, sometimes mocking or even biting. In this correspondence, Alexander von Humboldt appears as a part of a widely ramified family that played an important role in Berlin’s society.

Fig. 1: Alexander von Humboldt, Gabriele von Bülow: Briefe. Ed. by Ulrike Leitner and Eberhard Knobloch. De Gruyter Akademie Forschung 2023. (Beiträge zur Alexander-von-Humboldt-Forschung 47). 570 p. I thank the German Literature Archive in Marbach for permisson of publication.

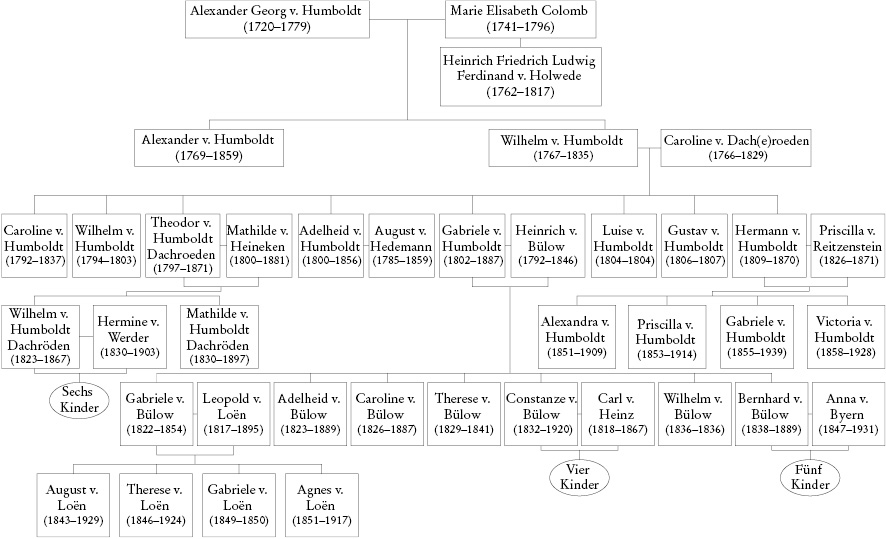

The brothers Humboldt are known to have had a significant influence on Prussian culture in different ways: Alexander as a scientist and a promoter of science, while Wilhelm – in the fields of education and linguistics, as a reformer in the school and university system and as a Prussian diplomat. The differences were also evident in their private lives: while Alexander did not start a family and there is no evidence that he had any close relationship, Wilhelm married Caroline von Dachroeden in 1791. The couple had eight children, three of whom died young. Gabriele was the fifth child. She was born in Berlin in 1802 – after Caroline (who remained unmarried), Wilhelm, Theodor and Adelheid. The youngest son, Hermann, was born in Rome in 1809.

Despite their differences, the brothers had a close bond with each other. This family closeness (in addition to the improvement of his financial situation by the Prussian king and the completion of his American travels) was one reason for Alexander’s return to Berlin in 1827. Wilhelm, however, died as early as 1835.

Fig. 2: Family tree (Humboldt 2023, 8).

Gabriele had already married Heinrich von Bülow in 1821, who had entered the Prussian service as an assistant to Wilhelm von Humboldt. After several years in the Prussian Foreign Office in Berlin, Bülow was appointed as an ambassador to London in 1827. Gabriele followed him with her three daughters, Gabriele, Adelheid and Caroline, born between 1822 and 1826, at the end of March 1828, so she was still able to enjoy the social life in Berlin and Tegel and the closeness of her family. She also attended Alexander von Humboldt’s famous “Cosmos Lectures” at the Berlin Sing-Akademie, which she graphicly described to her husband:

Today, Uncle’s lecture was again incredibly interesting, and Mr. Saphir’s joke only applied to the first half. He had said in the Courier: ‘The hall did not grasp the audience, and the female audience did not grasp the lecture’. Sometimes he may well be right as far as I am concerned, but it is very rare that I did not grasp it at all, because understanding and remembering are also different things. Each time the lectures become more beautiful, there is a perfect clarity in them and such a grandeur of views that they really have an uplifting effect on the mind and spirit. My uncle’s lecture is also becoming more and more beautiful and free, and he very rarely reads anything out, as he did at the beginning, which was always unpleasant for me.1

Two more daughters were born in London. As the wife of a diplomat, Gabriele played an important social role in London, but as a mother of several daughters, she did not find it easy to be separated from her children, which was often necessary due to her representational duties. In 1833, she was finally able to visit her family again after a long absence, but then remained close to her father for two years due to his illness, living partly in Tegel and partly in Berlin. During this period, Humboldt looked after his niece, as the following letter from Humboldt shows:

For a man who has always lived solitary in the world, I am not a bad relative – I pride myself on understanding the joys of family life gladly and with heartfelt sympathy. I shall see where family life degenerates entirely into a business life, into a series of petty material cares, which divert the mind from nobler sentiments, and yet, with the curse which God has laid upon the prose of the material (domestic and political) world, defeat their purpose of so-called usefulness. You, my dear, are indeed destined to be a wife, a mother of beautiful children, a friend, an extremely pleasant presence in the larger social circles of the bonds of kinship, to give charm and grace. So much that is both inward and outward, such sunniness, depth of feeling, liveliness of sympathy, strength of soul in the great, gloomy moments that we experienced together and whose memory your lovely image, dear Gabriele, eternally brings back to my soul […].2

Heinrich was only rarely able to go on vacation during this time, so letters were again exchanged between London and Berlin. Gabriele only returned to London after her father’s death on April 8, 1835, where she stayed for just over a year. In the fall of 1836, she came back to Berlin with little Wilhelm in his coffin, who had died shortly after his birth and was now to be buried in Tegel. She then stayed in Berlin mainly because of the lower cost of living, the better educational opportunities, and the confirmation of her daughters. In 1838, the eagerly-awaited male offspring Bernhard was born. Heinrich von Bülow was unable to make it in time for the christening, so his uncle Alexander – like the sculptor Christian Daniel Rauch – became godfather.

Bülow had often expressed the wish to return to Berlin for good, but the London conferences to resolve the European crises of the 1930s required his presence in London. Alexander von Humboldt used his influence to support Bülow’s wish, who was overworked and increasingly felt the deterioration of his health. He was granted leave twice during this period, but was only able to leave his post in London completely once the negotiations had been concluded. He was now to become the Prussian envoy to the Bundestag in Frankfurt/Main, where the whole family moved in October 1841. However, Bülow was already appointed to the post of Minister of Foreign Affairs in Berlin in March 1842. During his trip to Stolzenfels on the occasion of the British Queen Victoria’s visit in 1844, he fell ill with a stroke. He died shortly afterward, on February 6, 1846.

In addition to the addressee and her children, other relatives also play a noted role in the correspondence. Above all, there is the Hedemann couple.

In 1815, Wilhelm von Humboldt’s daughter Adelheid married the 16 years older August von Hedemann, who had been adjutant to Prince Wilhelm of Prussia since 1807. They had no children, but Adelheid played an important role as aunt to Gabriele von Bülow’s children, just as the two sisters were very close. She died in 1856.

Humboldt held the Hedemann couple in high esteem, as evidenced by his extensive correspondence with both of them.3 He had a particularly friendly relationship with August von Hedemann (in letters he called him “my dearest, most beloved friend”), probably also because he was closer to him in age. They had known each other since 1808, when Hedemann was in Paris accompanying the Prince of Prussia. As a Prussian general, Hedemann had to change his place of residence several times (Posen, Erfurt, Magdeburg) until he retired in 1852. Humboldt arranged with him the publication of Wilhelm von Humboldt’s writings after his death and other inheritance matters.

Caroline von Humboldt remained unmarried and died in 1837, barely two years after her father.

Uncle Alexander had a less close relationship with Wilhelm’s male descendants.

The last-born Hermann married the widowed Eleonore von Reitzenstein late in life (1850), with whom he had four children. Wilhelm von Humboldt had written about him to Gabriele:

I am quite satisfied with Hermann, if things continue like this. […] He loves his work, takes great pleasure in nature, and always retains a certain delicacy and refinement that goes beyond mere decency, even when dealing with many people, including uneducated ones. […] He will certainly become a good man if he retains his present simplicity.4

In 1848, Hermann was said to have socialist views, about which his uncle wrote to Augusta of Prussia with his typical mocking wit:

[…] that one of my nephews, Hermann, who is said to be a little red […] has married a pretty, somewhat corpulent person (moon face), who was once known in Berlin under the name of a Miss v. Reitzenstein. She is the widow of a Mr. von der Hagen and lived in Magdeburg. My family is very pleased with this connection and hopes that it will affect a ‘Teltow bleach’.5

Humboldt had already characterized him to Gabriele in 1845 as follows:

He has a peculiar but certainly noble nature; in his slow, taciturn solemnity of mind, your life, your conversation, your rapidity of ideas must seem quite uncanny to him. […] Prometheus, released from Spandau, has probably remained a stranger to him.6

The last remark refers to Theodor, born in 1797, who was probably the black sheep of the family. He married Mathilde von Heineken in 1818. The couple had two children (Mathilde and Wilhelm), both of whom are also mentioned in Humboldt’s letters to Gabriele, whereas Theodor had increasingly less contact with his family. He had already attracted negative attention in 1835 when he approached the king asking for a position as chamberlain. As can be read in the letters to Gabriele, a divorce, or at least a separation, was probably also being considered: “Unfortunately, through his sensuality, Theodor has gone astray and forced a lovable woman to leave him. He lives here completely estranged from us.”7

Theodor’s “stray” path even landed him in prison: My brother’s wicked son, Theodor, who tortured his once beautiful wife so horribly, was imprisoned in Spandau for four months last year, but the surrounding circumstances were so ignoble that [Justice A.] Uhden advised me not to interfere in any way.8

Everyday life with mutual care between Gabriele and her uncle plays a major role in the letters. Gabriele looked after him during his frequent illnesses. There were also gifts, birthday and Christmas visits. Humboldt usually celebrated his birthday in Tegel, and he also frequently spent his Sundays there.

Biographies often emphasize that for Humboldt, Gabriele and her family were a substitute for a family of his own, which he himself had not founded. Furthermore, the uncle provided a significant support for Gabriele during Heinrich von Bülow’s many official absences and even more so during her long widowhood. The youngest son was only eight years old when his father died, and she also consulted with the male relatives Hedemann and Humboldt on matters concerning his upbringing and education. Many affectionate details in the letters show that he also proved to be an empathetic uncle and great-uncle:

The box contains three bottles of genuine Parisian perfumes for you from my meager supply […] According to the great principle of celebrating the monarch’s birthdays by donations and charity to the children, the perfumes are trimmed with a little sugar, under which there is also a packet of dices, because I have conceived the spiritual idea that the ladies should throw them for the sugar.9

From his last trip to Paris, he brought the girls “three silk ball gowns and a bonnet à pluye d’or [golden rain hat]” and a microscope from Paris for the 10-year-old Bernhard. For the microscope, he obtained microscopic specimens from his friend, the mineralogist Christian Gottfried Ehrenberg. (See the letters of January 19, 1848, and January 21, 1848, Humboldt 2023, 239–243).

Scientific topics were also discussed in the letters, such as the appearance of a comet in 1842: “It is very praiseworthy, dear Gabriele, that you first discovered the comet with your naked eyes in Tegel. Encke, to whom I immediately dispatched, confirms your brilliant discovery.”10

Although Gabriele did not run a salon in the true sense of the word, socializing at the Tegel Palace or in her city apartment was a necessity for her and also important for the younger daughters’ entry into society. Moreover, Humboldt expressed his care for them by bringing interesting guests with him. In addition, he was able to offer his visitors special experiences with the Tegel Palace and the antiquities collected there by his brother, as he had hardly any opportunities to receive guests in his Berlin apartment.

The sculptor Christian Daniel Rauch was also usually invited to Humboldt’s birthdays in Tegel: “He is actually very much a part of our family.” (letter dated July 28, 1856, Humboldt 1923, 457). The relationship was rooted in the sculptor’s long friendship with Wilhelm von Humboldt’s family from his time in Rome. Rauch gave his children drawing lessons and developed a close friendship with Caroline, who was particularly interested in art, as he later did with Gabriele von Bülow.

The painters Wilhelm von Kaulbach and Eduard Hildebrandt and the court gardener Hermann Ludwig Sello were also welcome guests at Gabriele’s home.

Another important friend of Alexander von Humboldt was Karl August von Varnhagen, who also had contacts with the Bülows, but to a greater extent with Heinrich von Bülow. Varnhagen reported on a visit on February 26, 1844:

In the evening at Bülow’s […] Mrs. von Bülow leads me to the Duchess von Talleyrand, the glamour of today’s salon, the acquaintance is quickly made, we speak of her sisters […] of her uncle Talleyrand, von Metternich, von Tettenborn, – she comes from Vienna […] I did not get home until after eleven.11

Humboldt was also present in her salon that evening.

The Dorothea Talleyrand-Périgord mentioned here, later Duchess of Sagan, had returned to Prussia from Paris in 1840 and lived in Berlin, Sagan and France. She was a regular guest of the royal family and played a special role in Berlin society thanks to her origin and wealth. Gabriele von Bülow, whom she already knew from London, paid Dorothea a courtesy visit after her arrival in Berlin. She was godmother to her daughter Constanze von Bülow, who was born in London on April 10, 1832. (Sydow 1919, 301) When she subsequently came to Berlin, she was in regular contact with Humboldt, who also visited her at the Sagan Palace, which she had lived in since 1840 and which subsequently developed into a cultural center.12

The Italian artist Emma Gaggiotti-Richards, who also painted a portrait of Humboldt, became one of his most important contacts in his final years. He held her in high esteem. This was one of the rare occasions that Humboldt invited to his apartment. Naturally, she was also invited to Tegel for an artists’ dinner. (Letter dated May 17,855, Humboldt 2023, 436)

Ludmilla Assing, Varnhagen’s niece, “who has the luxury of drawing beautifully and writing quite tastefully on the whole”, also plays a role in the correspondence, albeit a minor one. Humboldt sent the biography she had written of Elisa von Ahlefeldt (a well-known salonnière) to Gabriele with recommendations. (Assing 1857, see also the letter dated July 1, 1857, Humboldt 2023, 473)

Humboldt likewise mentioned his support for others in his letters, e.g., for the Schlagintweit brothers, in particular for the financing of their projects. (Letter dated 15. 5. 1854, Humboldt 2023, 412)

It is well known that Humboldt often complained about the “pendulum swings” between Potsdam and Berlin, which he was obliged to do in his role as chamberlain. He often took with him the research materials necessary for writing the “Cosmos”, which he worked on until the end of his life.

From 1842, Humboldt lived in Berlin at Oranienburger Street 67, the property of Joseph Mendelssohn (who allowed him to live there for free), where he was looked after by his servant Johann Seifert and his family. Downstairs, the old widow Körner lived, the mother of the poet Theodor Körner, who died in the wars of liberation in 1813:

When you die, you don’t have to move out because of the house sale. Good old lady Körner passed away gently this night, almost without knowing it, at the age of 82. She was still in the garden the day before yesterday, talking to my black parrot. Yesterday, she complained of pain in her side. She wants to be buried in Mecklenburg, next to her son. […] The king, the kings in Prussia have done nothing for the poet’s memory. He is worthy of something better and greater: his songs will be sung on the battlefield.13

As Gabriele was often alone due to Bülow’s official absences, Humboldt accompanied her to particular social events. For example, he arranged special window seats for her and the children on the occasion of the laying of the foundation stone for Friedrich II von Rauch’s monument on June 1, 1840, in Berlin:

Professor Weiss has splendid windows, of course, some distance away, about the width of the university courtyard, one of which he offers for you, the sister, and all the children, even the youngest and the English Bonne. I have just been to see the local of his study and to make sure of the places for the time being. You can see the place where the foundation was laid, where there is nothing to see, you can see the processions, hear the singing, admire the guilds with their flags. […] The best way to enter the university building from the back is through Dorotheen-street and then on foot from behind Weiss in the bel étage.14

The Tegel Palace, Wilhelm von Humboldt’s favorite place, became the joint property of Caroline and Adelheid after his death, and then Adelheid’s alone after Caroline’s death. After Adelheid’s death in 1856, it was inherited by Gabriele, who had already been the main user of the house in the summer months since the 1840s, mainly because of her young children and the Hedemanns’ official absence. Humboldt came here regularly and often brought guests with him, including the Prussian king. As is apparent from the following quote, he also took care of the planting of the garden by sending Sello (the court gardener of Sanssouci):

He will give precise instructions for planting to break up the desert with Italian cane, wonder tree (Ricinus) broad-leaved Hemerocalles as it already glows on the lawn in Sanssouci. He also wants to deliver all the plants in the fall, the gardener only has to come here. I won’t forget anything that makes you happy, my dear […].15

From Potsdam, Humboldt sent Gabriele reports on special events at the palaces Neues Palais, Marmorpalais, Sanssouci Palace, Charlottenhof Palace and Babelsberg Palace. Princess Augusta and Prince (later Wilhelm I) of Prussia, usually referred to by Humboldt in his letters as “Babel” for short, resided in the latter. Examples illustrate his role at the royal court:

As I am not alone, my dear, I can only write a few lines. Unfortunately, it is not possible for me to determine the day on which I could have the pleasure of visiting you. There are usually only 5–6 of us dining with the king, and my departure causes all the more sighs as he wants to ask some people from Berlin […] whom I am to entertain. Yesterday evening we were in Babel with 160 cadets; the king played cannibalistic cheer with the children who threw thick balls at his head […].16

My dear Gabriele. […] We were only at 9 o’clock last night for tea and supper in the icy Marble Palace […]. The king was quite miserable and shook Olympus by sneezing. I was afraid he would become seriously ill […].17

Or in the Neues Palais in Sanssouci on the occasion of the reception of Tsarina Mother Alexandra Feodorovna with Alexander II of Russia and other kings, princes and dukes in May 1856:

This evening, I must of necessity appear again in the New Chambers! from 8–11 o’clock with the Imp[erial], Prussian, Mecklenburg and Dutch ladies-in-waiting, while the sick empress, who had gone for a walk to the Pfingstberg! yesterday morning out of restlessness, indulges with 14 high relatives on the classical hill in daily recurring lectures by my colleague Schneider until 11 o’clock in the evening. […] The empress is thinking of staying here for a month. So far, I have not been able to see neither the king nor the queen. […] The emperor wants to live close to the mother, not in the New Palace but in the New Chambers, so that poor Dönhoff has to live bitterly in my room in the garden house in Charlottenhof. This morning, the queen had a rendez-vous with both Saxon queens for a peculiar celebration of the centenary of the birth of their late common father, King of Bavaria.18

Humboldt also took part in the consecration of the Church of Peace (German: Friedenskirche) in Potsdam, for which Frederick William IV had already made a sketch as crown prince in 1839 based on an early Christian Roman church. Construction by Ludwig Persius began in 1843 and the building was consecrated on September 24, 1848. The apse contains a Byzantine mosaic acquired in 1834. Humboldt also reported on festivals and concerts in the city palaces and visited the German entrepreneur, sugar manufacturer, patron and city councilor in Potsdam, Ludwig Jacobs.

As is well known, Humboldt had requested regular visits to Paris after his return to Prussia following his twenty-year stay in Paris in 1827 and his appointment as chamberlain. During these eight stays in Paris (between 1830 and 1848), most of which lasted several months, he worked primarily on the last part of his American journey Examen critique and on the report of his Russian journey (1829) Asie centrale, and later on Kosmos (Vol. 1: 1845). In Paris, he met members of the court at audiences or on other occasions and reported on this not only in the so-called “diplomatic reports” to the court in Berlin,19 but also in his private letters, which thus form an interesting counterpart to the official reports. In the letters to Gabriele in particular, one senses that his stays in Paris were about more than just collecting material for his publications. Each time was a return to his second home:

I went straight to breakfast at the Café de Foy, then to Arago, whom I found very well and visit twice a day, then to the embassy […] Today, on the 2nd day, I felt what it means to have lived in one place for 23 years. I feel as if I had never left Paris, I know every stone, and I have lived here only occasionally since 1827, always in the same rooms, in the same furniture. Life here is so pleasantly easy and indescribably independent when one has been in Berlin, as the world’s address book, for a long time. This morning I had breakfast at Guizot’s, where the ancient mother makes an amiable impression.20

Gabriele also wrote to him when he was in Paris. Only a few of her letters have survived, but Humboldt’s reply reveals the warmth and closeness between the two relatives:

I cannot, dearest Gabriele, thank you vividly enough for your letter, which is never too long, full of warmth and grace of feeling and expression. Human life, when it does not bring great suffering, consists of a series of small incidents, one cause the other, and when one writes them down or tells them to an absent person, one considers them uninteresting, which nevertheless brings joy in the connection and in the certainty that nothing frightening is on the horizon. You give me this pleasure, my dear, when you write to me about Bülow’s busy well-being, about your lovely children, the beautiful grandson and the people of Erfurt. It is almost the same with political events, it is a kind of small life in which one has lost faith in great things, even if one is always fighting a bloody battle somewhere in so-called peaceful Europe […].21

Humboldt’s letters to Gabriele cover the second third of the 19th century. Beginning with Humboldt’s visit to Paris shortly after the July Revolution, the death of Friedrich Wilhelm III, the Rhine crisis and change of throne in Prussia in 1840, and the 1848 revolution, it is also a period of great political upheaval in Europe. In Humboldt’s life, it was a time in which he exerted a stronger influence on the Prussian scientific and cultural landscape, particularly through his proximity to Frederick William IV, but was then increasingly marginalized as he advanced in years.

The correspondence reveals Humboldt’s efforts to provide Gabriele with the latest news from court, his circle of acquaintances and political life. As a chamberlain, Humboldt constantly participated in court companies. His task was to provide intellectual entertainment for the royal dinner party, including reading aloud, for example from the Cosmos, on which he was currently working, while the company “slurped up old frog legs, the cat’s porridge of Bavarian noodles and the parsley soup, a historical broth, and rattled all the plates.”22

Just as Humboldt mocked society in his letters, it was certainly also sometimes bored by his readings.

Heinrich von Bülow’s important activities as Prussian ambassador in London (the so-called Belgian question and the Oriental crisis) are also discussed. In 1831, following revolutionary unrest, the Great Powers of Europe, Great Britain, France, Austria, Prussia, and Russia, recognized Belgium’s independence and its separation from the Netherlands. As a result, this led to repeated European conflicts, including the threat of war, especially after the controversial election of Leopold I of Saxe-Coburg as King of the Belgians. As Prussian envoy in London, Heinrich von Bülow played an important role in the negotiations, which lasted until 1839.

In almost all letters from mid-1839 to the end of 1839, Humboldt reported to his niece on the progress of the negotiations, which he learned about through his contacts. It was also about the eagerly desired vacation for the christening of his son Bernhard on August 12, 1838, for which he repeatedly (but unsuccessfully) approached the Minister for Foreign Affairs, Heinrich von Werther:

As for this coming, which I so much desired, I have asked Werther about it very carefully, but have received little satisfaction. He says that Bülow can foresee this possibility better than he can, but he (Werther) believes so strongly in a speedy and real conclusion to the Belgian affairs that he is concerned that the departure cannot take place before the end of September or the beginning of October. If there were an interruption to the negotiations, then of course things would be different.23

Humboldt also used his contacts in Paris to expedite the matter in Bülow’s favor:

I had a long audience with King Louis Philippe in the cabinet: he was, as usual, very friendly, full of praise for Bülow’s talent and much praised kindness. As I had the task of reminding him not to make new difficulties for Leopold out of love of money, he went deeply into the Belgian cause, but unfortunately left me with the impression that he still considered it possible to make the division of the debt more favorable for Belgium […]: King Leop[old] would be very unpopular anyway because of the cession of the territory, if he were to pay 20 million francs a year, this would be ¼ of the entire income … I replied that when France and Belgium signed the 24 articles, they had considered the execution and payment possible at that time and that Belgium had become richer, not poorer, through trade since that time; many states (France itself, England, Prussia, Austria) had to pay ¼ of the income on the interest.24

Gabriele usually sent such information directly to Heinrich in London. (Sydow 1919)

Dear Gabriele. The Belgian news (of the newspaper) would not please me if Bülow’s letter and W. Russell’s identical and hitherto certain news here had not announced the near end […] My cold is developing like the Belgian affair […].25

Even after the negotiations were concluded, the signing of the treaty dragged on until April 19, 1839 (Sydow 1919, 445), after which Bülow was finally allowed to leave and reached Berlin on April 28, 1839.

Humboldt also supported Bülow when he became embroiled in diplomatic entanglements with the British statesman Henry John Temple, 3rd Viscount Palmerston, in the negotiations on the Eastern Question in 1840, in which the British ambassador in Berlin, George William Russell, was also involved. Humboldt reported to Heinrich von Bülow:

Lord Palmerston has denounced you here in the most hateful manner for frowning upon the association with the French. I have just returned from Charlottenburg, where I read the denunciation to the king in his cabinet. He listened to it with contempt, justifies you completely and wants to give you satisfaction. […] It was reported to the king that […] William Russell was found in a tremendous agitation, because Lord Palmerston complained bitterly of your conduct, of proposals which you […] were supposed to have made unilaterally. The king had just heard the news of this […] and laughed at it […].26

He wrote frustratedly to Gabriele:

My bitter reflection on English statesmen is this: they talk eternally of their loyalty and religious and moral sentiments, the friendship they show to other statesmen of the Continent is that which the nobles cherish against inferiors. They allow themselves everything as long as something independent confronts them, then they become insolent, because we people of the Continent belong to an inferior human race. Nor do we need political liberty; that is a fruit that can only spring from English soil and belongs only to the English people.27

The European crisis was not ended until a year later, on July 13, 1841, when the five Great Powers of Europe concluded the London Straits Convention with the Ottoman Empire.

Humboldt’s eighth and last trip to Paris (October 1847 to mid-January 1848) took place in a politically charged atmosphere. As is well known, Louis Philippe’s reign was increasingly shaken during this period by a renunciation of liberalism, scandals, and cases of corruption (letter dated November 10, 1847, Humboldt 2023, 232), until he was deposed in the February Revolution. After his return, Humboldt reported on this development and the political commitment of his old friend François Arago, who became a member of the provisional government founded on February 23, visibly affected:

I am writing again, my dear ones, not just to say that I am doing well and go out, nor to give you news that have already gone from the Cologne newspaper [“Köllner Zeitung”] to the state newspaper: I am writing because, especially since today, I feel very sad. The great Republic proclaimed, Arago, who has not been mentioned at all so far and has not been at any banquet, today at the head of the provisional republican government, the poor duchess with her two children entering the Chamber of Deputies on foot to present herself as regent, there mocked, roughly treated, forced to flee; more bloodshed than in the July Days; the Tuileries devastated after a two-hour battle, and after the king, the duchess and their children, who showed themselves on the balcony, were shot at! The king seems to have fled to Laeken near Brussels, and the duchess is believed to still be hiding near Paris. […] The proclamation of the Republic, which I predict will be short-lived, but which makes me very unhappy because of the severe judgments passed on my friend and will probably lead to war, is inciting and agitating everyone here to move even further away from a timely and dignified compliance in corporative relationships.28

This was followed by the revolution in Germany, which Humboldt addressed in his letters to Gabriele in the years from 1848 onwards, as did further developments (the flight of the future Wilhelm I, formation of the government, constitutional debate, restoration, the formation of a nation-state, election of the emperor, and Schleswig-Holstein War, etc.), especially as her son-in-law Leopold von Loën was involved in the suppression of the uprising in 1848, as he was in command of the Berlin Palace Guard. (Sydow 1919, 511) Humboldt rejected the outbreak of revolutionary violence that had erupted in the flight of the Duchess of Orléans, bloodshed, battles in the Tuileries, shots fired at the king, etc. These riots by the “mob” were due to the wrong and hesitant actions of the monarchs. (Leitner 2008)

Humboldt told Gabriele about his participation in the funeral procession in Berlin for those who died in March:

I come from the funeral procession. I have never experienced greater order and calm in an immense crowd. Not an indecent sound, not a political word, as one feared such things. The king wanted us to go with him. I joined the students, walked alongside Prorector Johannes Müller and was treated very kindly by the public everywhere. At half past twelve we were at the Gendarmenmarkt where 173 coffins stood at the church portal: in addition, there were 50 more from the Werdersche Church. The families of the deceased, sobbing brides, many very small children … were heart-breaking to see – a procession of probably 5–600 people. Sydow’s (the priest’s) speech at the coffins seemed very cold. He had probably wanted to avoid any political allusions, so (as far as I heard) the king, who showed himself so beautifully and courageously yesterday, was not mentioned. Then there were speeches by true and German Catholics, and also a rabbi. The funeral procession went in two long trains. The king is said to have stepped onto the balcony each time the coffins arrived: I did not see it because the university remained separated from the coffins by the mourners. I remained on my feet for 3 ½ h[ours] and only left the procession at the Alexander Square.29

When Wilhelm of Prussia fled Berlin on March 19, 1848, as the population blamed the “Kartätschenprinz” [“case shot prince”] for the bloody clashes of the March Revolution of 1848, Humboldt shared Gabriele’s sympathy for Princess Augusta, who had retreated to Potsdam with her two children.

Humboldt also reported on the election of the emperor. On March 28, 1849, the Frankfurt National Assembly sent a deputation to Berlin, which was received by Friedrich Wilhelm IV on April 3, 1849, and offered him the imperial crown, which he declined:

Despite the king’s usual cheerfulness (I was still in Charlottenburg yesterday evening), there is still a lot of trouble here due to the double inconvenience of the Imperial Crown because of the deputation of 33 electors from Frankf[urt], who will only arrive on the 2nd, and because of the indiscretion of the local chambers, which also want to strengthen the king’s convictions. The king is so irritated by all this that he seems to me rather inclined not to want to receive anyone at all. But the ministers will soften the blow. I don’t need to tell you that there is no question of accepting the crown. Veto suspension, primary elections, fundamental rights, envoys from Bavaria, Hanover, Wuerttemberg and Saxony abstaining from all voting. (Austria, the now so powerful Austria, not included.[)] One cannot receive from the hands of those who previously insulted, to whom one does not concede the right to dispose unilaterally of the empire. But it is a great public act, one can reject it, but it must be done with skill and dignity, openly in a prepared, read speech. I have little confidence in all this.30

In 1855, he described his deployment as a primary voter “with 60 postillons” (“riding apostles of progress”): they had “beaten all the ultras”. (Letters of October 2 and 8, 1855, Humboldt 2023, pp. 445–447).

As Humboldt’s relationship with the king was particularly cordial, almost friendly, the news of the king’s illness (presumably several strokes) deeply affected him:

Just a few words, dear Gabriele. Physical recovery is increasing, not mental recovery. I went to the Church of Peace because it was a way to see the queen on this holiday, which was not celebrated at the castle. The queen had not seen me, but she had been told. She regretted not having approached me, and told me very kindly that she wanted to see me alone after dinner. She was all alone, very sad, and sympathetic to me, talking, of course. The physical improvement is increasing, but not the intellectual. He knew nothing of his illness or its duration, no memory of the bloodletting, none of the Emperor of Russia; he believed he had only seen him last year, he complained that he could not express himself clearly, inventing incomprehensible, self-invented words! He could only find the names as connected phrases; he felt very tormented and always sad. Once, when he thought he was alone, he exclaimed: “God have mercy on me.” He is aware of his mental weakness. He is not paralyzed; he got up today and came to the Queen’s room for a few minutes. All this is touching and deeply distressing.31

Prince Wilhelm took over as deputy on October 23, 1857, but the actual regency was not assumed until the following year:

I am writing, dear Gabriele, what you perhaps already know […] Yesterday, the queen believed that she could present the king authorization for interim governance for his signature. He was resistant for a long time and said (which indicated full consciousness): ‘I will consider it’. The queen said: ‘I will not speak to you of it again until you know for yourself.’ Today, [on] Friday, he declared his decision and signed. Pr[ince] of Pr[ussia], Pr[ince] Carl and Manteuffel were in the room. However, the king did not appear to notice them.32

The letters also provide new details for biographical research. New, for example, is the fact that Humboldt was unable to make one of his regular trips to Paris in 1840 due to political tensions between Prussia and France. He was advised to “only go to Paris […] when peace is assured”. Newspapers reported that he had been called back in the fall of 1840, while being already en route.

In 1846, Charlotte Diede, born Hildebrandt, sent to Humboldt the original letters of her correspondence with Wilhelm von Humboldt, which Wilhelm had written between 1814 and 1835 after a brief acquaintance as a young student in 1788. After consultations with Gabriele, August von Hedemann and Varnhagen and some back and forth, Therese von Bacheracht, a friend of Diede who had died in the meantime, took over the publication. (Sternagel 2021)

And Humboldt reports on his companion during the trip to America, Aimé Bonpland, whom he had not seen since his departure from France in 1816:

I have a long long letter from Bonpland in Montevideo. He is 76 years old, very strong and wealthy. He has so much livestock that he could have lost 19,000 sheep, cattle, and horses in one year due to Indian raids. He speaks of orange trees in his garden, one of which gives 5 to 6000 fruits every year – and yet he wants to return to France after living in this paradisiacal climate for 30 years. It will probably remain a foolish wish.33

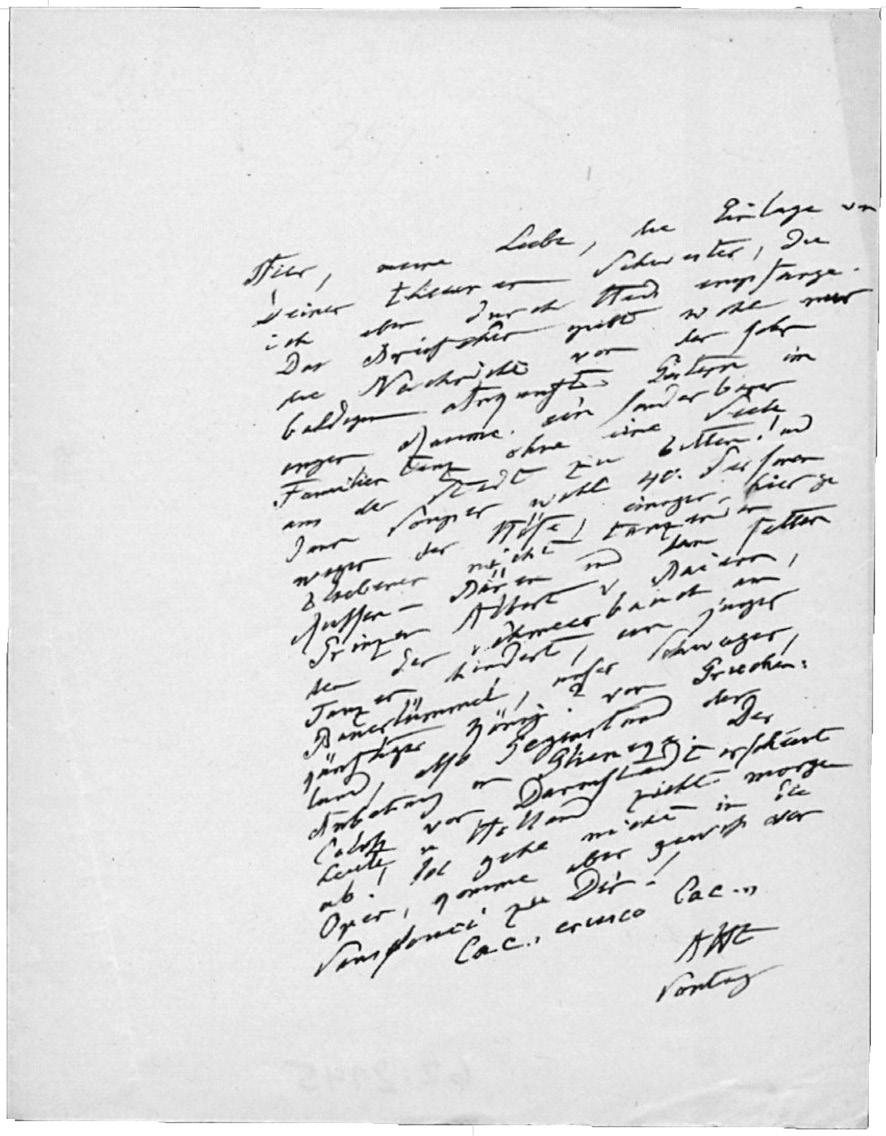

Humboldt’s handwriting became increasingly “illegible” as he advanced in age, as he himself put it. Despite tremendous efforts (also with the help of the wider Humboldt research community, for which I express my sincere thanks), in individual cases, the reading, unfortunately, remained dubious or even entirely impossible.

Fig. 3 Humboldt’s manuscript.

However, the dissatisfaction with such cases (known to all editors) is lessened by the fact that Humboldt fared no better when deciphering them himself, as the following example shows: Humboldt had received a letter from Hedemann with rather illegible words, which Humboldt deciphered as “Cac. erusco Cac.” and sent it on to Gabriele with the remark: “Seems to me a touch of Latin in which I can only read erusco which means nothing: erubisco means I blush […]! But the evil Cac….”34

Fortunately, Hedemann’s letter has been preserved and, with immense effort, the words “‘Caeterum’ censeo Carthaginem” can be deciphered.35 Hedemann therefore presumably meant the saying: “Ceterum censeo Carthaginem esse delendam.”

Despite such imperfections, the present correspondence presents a picture of Humboldt’s relationship with his niece Gabriele with some hitherto unknown facets from the last third of his life and thus offers material to supplement the previous editions of letters in order to make the scientist, Prussian chamberlain, author, friend and uncle, who was hidden behind the veil of his fame, more visible.

Humboldt is known to have received and written a multitude of letters, the fact he often complained about:

The old saying goes:

Man is a dog in heat

grows old like the Egyptian cow

and increases from day to day

The proverb does not say in what he increases. I say in correspondence.36

Fortunately for Humboldt research, many of his letters have been preserved and published in 20 volumes to date, but in hardly any other letters one can find such a variety of descriptions of his everyday life, honest opinions and unvarnished views of historical personalities and facts as in the private letters to Gabriele von Bülow.

Assing, Ludmilla (1857): Gräfin Elisa von Ahlefeldt, die Gattin Adolphs von Lützow, die Freundin Karl Immermanns. Eine Biographie. Nebst Briefen von Karl Immermann, [Anton Wilhelm] Möller und Henriette Paalzow. Berlin 1857.

Erbe, Günter (2009): Dorothea Herzogin von Sagan (1793–1862). Eine deutsch-französische Karriere. Cologne/Weimar/Vienna 2009 (Neue Forschungen zur schlesischen Geschichte, 18).

Humboldt, Alexander von (2011): Alexander von Humboldt – Familie Mendelssohn. Briefwechsel. Edited by Sebastian Panwitz and Ingo Schwarz with the collaboration of Eberhard Knobloch. Berlin 2011 (Beiträge zur Alexander-von-Humboldt-Forschung, 34).

Humboldt, Alexander von (2023): Alexander von Humboldt – Gabriele von Bülow. Briefe. Edited by Ulrike Leitner with the collaboration of Eberhard Knobloch. Berlin 2023 (Beiträge zur Alexander-von-Humboldt-Forschung, 47).

Leitner, Ulrike (2008): “Da ich mitten in dem Gewölk sitze, das elektrisch geladen ist”. Alexander von Humboldts Äußerungen zum politischen Geschehen in seinen Briefen an Cotta. In: Kosmos und Zahl. Beiträge zur Mathematik- und Astronomiegeschichte, zu Alexander von Humboldt und Leibniz. Edited by Hartmut Hecht et al., Stuttgart 2008, pp. 225–233 (Boethius, 58).

Müller, Conrad (ed.) (1928.): Alexander von Humboldt und das Preußische Königshaus. Briefe aus den Jahren 1835–1857. Leipzig 1928.

Péaud, Laura (2015): Die diplomatischen Berichte Alexander von Humboldts aus Paris zwischen 1835 und 1847. In: “Mein zweites Vaterland”. Alexander von Humboldt und Frankreich. Edited by David Blankenstein, Ulrike Leitner, Ulrich Päßler, Bénédicte Savoy. Berlin 2015 (Beiträge zur Alexander-von-Humboldt-Forschung, 40), pp. 15–31.

Sternagel, Renate (2021): Alexander von Humboldt, Therese Bacheracht und die “verhängnissvolle Prosa des Lebens„. In: HiN – Alexander von Humboldt im Netz. Internationale Zeitschrift für Humboldt-Studien, 22 (43), pp. 83–100, https://doi.org/10.18443/332.

Sydow, Anna von (1919): Gabriele von Bülow – Tochter Wilhelm von Humboldts; ein Lebensbild. Aus den Familienpapieren Wilhelm von Humboldts und seiner Kinder 1791–1887. 19th ed. Berlin 1919.

Varnhagen von Ense, Karl August (1994): Tagesblätter. Edited by Konrad Feilchenfeldt. Frankfurt a. M. 1994 (Karl August von Varnhagen. Werke in fünf Bänden, Bd. 5).

1 “Heute war des Onkels Vorlesung wieder unendlich interessant, und Herrn Saphirs Witz traf nur für die erste Hälfte zu. Er hatte im Courier gesagt: ‘Der Saal faßte nicht die Zuhörer, und die Zuhörerinnen faßten nicht den Vortrag.‚ Mitunter mag er wohl Recht haben, was meine Wenigkeit betrifft, allein ist es doch sehr selten, daß ich es gar nicht faßte, denn verstehen und behalten sind auch noch verschiedene Dinge. Mit jedem Male werden die Vorlesungen schöner, es herrscht eine vollendete Klarheit darin, und eine solche Größe der Ansichten, daß sie wirklich erhebend auf Verstand und Gemüth wirken. Auch wird des Onkels Vortrag immer schöner und freier, er liest auch sehr selten etwas ab, wie zu Anfang, was mir immer nicht angenehm war.” (Sydow 1919, 194 f.)

2 “Für einen Menschen, der immer vereinzelt in der Welt gelebt hat, bin ich kein schlechter Verwandte[r] – ich rühme mich die Freuden des Familienlebens gern, und mit inniger Theilnahme zu verstehen. Ich werde da sehen wo das Familienleben ganz in ein Geschäftsleben, in eine Reihe kleinlicher materieller Sorgen ausartet, die das Gemüth von edleren Gefühlen ableiten und bei dem Fluch, den Gott auf die Prosa der materiellen (häuslichen und politischen) Welt gelegt, doch ihren Zwek der sogenannten Nüzlichkeit verfehlen. Du, meine Liebe, bist recht eigentlich geschaffen als Gattinn, als Mutter schöner Kinder, als Freundin, als überaus angenehm auftretend in den grösseren gesellschaftlichen Kreisen der Bande der Verwandschaft Reiz und Anmuth zugeben. So viel Inneres und Aeusseres zugleich, solche Sonnigkeit, Tiefe des Gefühls, Lebendigkeit der Theilnahme, Stärke der Seele in den grossen, trüben Momenten die wir zusammen erlebt und deren Andenken mir Dein liebes Bild, theure Gabriele, ewig zurükführt vor die Seele […]”. (letter dated September 29, 1835, Humboldt 2023, 63).

3 Also the German Literature Archive in Marbach, for the most part not yet edited.

4 “Mit Hermann bin ich, wenn es so fortgeht, recht sehr zufrieden. […] Er hat Liebe zu seiner Beschäftigung, große Lust an der Natur, behält immer, ob er gleich mit vielen, auch ungebildeten Leuten umgeht, eine gewisse Zartheit und Feinheit, die über den bloßen Anstand hinausgeht. […] Er wird gewiß ein guter Mensch, wenn er seine jetzige Einfachheit behält.” (Sydow 1919, 281).

5 “[…] daß einer meiner Neffen, Hermann, dem man nachsagt, daß er ein wenig rot ist […] eine hübsche, etwas dicke Person geheiratet hat (Mondgesicht), die in Berlin einst unter dem Namen eines Fräulein v. Reitzenstein bekannt war. Sie ist die Witwe eines Herrn von der Hagen und lebte in Magdeburg. Meine Familie ist über diese Verbindung sehr zufrieden und hofft, dass sie eine ‘Teltower Bleiche’ bewirken wird.” (Müller 1928, 322).

6 “Es ist eine sonderbare aber gewiss edle Natur, in seiner langsamen, wortarmen Feierlichkeit des Gemüths muss ihm Euer Leben, Euer Gespräch, Eure Schnelligkeit der Ideen ganz unheimlich scheinen. […] Der aus Spandau entlassene Prometheus ist ihm wohl fremd geblieben.” (Letter of April 1, 1845, Humboldt 2023, 284).

7 “Theodor ist leider! durch Sinnlichkeit auf Abwege gerathen und hat eine liebenswürdige Frau zur Trennung gezwungen. Er lebt hier von uns ganz entfremdet.” (Humboldt to F. G. Welcker, April 12, 1859, Bonn University Library).

8 “Der böse Sohn meines Bruders, Theodor, der seine einst schöne Frau so grässlich gequält, hat voriges Jahr 4 Monate Festungsarrest in Spandau gehabt aber die Nebenverhältnisse waren so unedel, daß [Justizrat A.] Uhden von jeglicher Einmischung mir abrieth.” (Humboldt to Henriette Mendelssohn, probably May 11, 1848, Humboldt 2011, 170).

9 “Die Schachtel enthält für Dich von meiner Armuth an echt Pariser Parfüms drei Flaschen […] Nach dem großartigen Prinzip, die Geburtstage des Monarchen durch Spendungen und Wohlthätigkeit an die Kindlein zu feiern, sind die Parfüms mit etwas Zuckerwerk verbrämt, unter dem sich auch ein Päckchen mit Würfeln befindet, weil ich die spirituelle Idee gefaßt habe, die Ladies sollten um das Zuckerwerk würfeln.” (letter dated May 28, 1834, Humboldt 2023, 61).

10 “Es ist ja sehr rühmlich, theure Gabriele, dass Du zuerst in Tegel den Cometen mit blossen Augen entdekt hast. Encke zu dem ich gleich schikte, bestätigt deine glänzende Entdeckung.” (letter dated August 24, 1842, Humboldt 2023, 140).

11 “Abends zu Bülow […] Frau von Bülow führt mich zur Herzogin von Talleyrand, dem Glanze des heutigen Salons, die Bekanntschaft ist schnell gemacht, wir sprechen von ihren Schwestern […] von ihrem Onkel Talleyrand, von Metternich, von Tettenborn, – sie kommt aus Wien […] ich kam erst nach elf nach Hause.” (Varnhagen 1994, 331, see also the letter of March 3, 1844, Humboldt 2023, 159).

12 The valuable archive holdings with her correspondence with famous contemporaries, including A. v. Humboldt’s letters, have been considered lost since 1945. They have only survived sporadically and in excerpts in the literature. This is another reason why the testimonies in Humboldt’s letters to Gabriele von Bülow are of great value. On the relationship between Humboldt and the Duchess of Sagan, see Erbe 2009, pp. 194–197.

13 “Wenn man stirbt, braucht man, wegen Hausverkauf, nicht auszuziehen. Die gute alte Körner ist diese Nacht sanft, fast ohne es zu wissen, entschlafen im 82sten Jahre. Sie war vorgestern noch im Garten und sprach mit meinem schwarzen Papagay. Gestern klagte sie über Reissen in der Seite. Sie will in Mecklenburg, neben ihrem Sohn begraben sein. […] Der König, die Könige haben in Preussen nichts für das Andenken des Dichters gethan. Ihm ward etwas besseres und grösseres: man wird seine Lieder auf dem Schlachtfelde singen.” (letter dated August 20, 1843, Humboldt 2023, 148).

14 “Professor Weiss hat prächtige Fenster freilich etwas entfernt, um die Breite des Universitätshof entfernt von denen er eines für Dich die Schwester und alle Kinder selbst die Kleinsten und engl[ische] Bonne anbietet. Ich war so eben bei ihm, um das Local seines Studirzimmers anzusehen und mich der Pläze vorläufig zu versichern. | 3 | Man sieht den Plaz der Grundlegung, an der nichts zu sehen ist, man sieht die Züge hört den Gesang bewundert die Zünfte mit den Fahnen. […] [Man] kann von hinten in das Universitätsgebäude hinein am besten durch die Dorotheenstrasse und dann zu Fuss von hinten bei Weiss in der bel étage eindringend.” (letter probably dated May 29, 1840, Humboldt 2023, 93).

15 “Er wird genaue Instructionen geben zu Pflanzungen um die Wüste zu unterbrechen mit italienischem Rohr, Wunderbaum (Ricinus) grossblättrigen Hemerocalles wie er schon auf Rasen in Sanssouci glükt. Er will auch alle Pflanzen liefern im Herbst, der Gärtner soll nur hieher kommen. Ich vergesse nichts was Dich freuet, meine Theure […].” (letter dated July 29, 1847, Humboldt 2023, 224).

16 “Da ich nicht allein bin, meine Theure, so kann ich nur wenige Zeilen schreiben. Es ist mir leider! nicht möglich den Tag zu bestimmen an dem ich die Freude haben könnte Euch zu besuchen. Wir speisen gewöhnlich nur zu 5–6 Personen mit dem König und mein Weggehen erregt um so mehr Seufzer, als er einige Personen aus Berlin bitten will […] die ich mit besprechen soll. Gestern waren wir mit 160 Cadetten Abends in Babel; der König spielte kannibalisch heiter mit den Kindern die ihm dikke Bälle unsanft an den Kopf warfen […].” (letter dated July 29, 1847, Humboldt 2023, 224).

17 “Meine theure Gabriele. […] Wir waren gestern Abend erst um 9 Uhr zu Thee u. Souper im eisigen Marmor Palais […]. Der König war recht leidend und erschütterte durch Niesen den Olymp. Ich war bange, er würde ernsthaft krank werden […].” (letter dated September 12, 1851, Humboldt 2023, 380).

18 “Ich muss heute Abend nothwendig wieder in den Neuen Kammern! von 8–11 Uhr bei den kais[erlichen] und preussischen und mecklenburg[ischen] und niederländischen Hofdamen erscheinen, während dass die kranke Kaiserin, die doch gestern morgen aus Unruhe nach dem Pfingstberge! spaziren gefahren war, mit 14 hohen Verwandten auf dem klassischen Hügel an täglich wiederkehrenden Vorlesungen meines Collegen Schneider bis 11 Uhr Abends schwelgt. […] Die Kaiserin denkt einen Monat hier zu bleiben. Bisher habe ich weder König noch Königin sehen können. […] Der Kaiser will der Mutter nahe, nicht im Neuen Palais, sondern in den Neuen Kammern wohnen so dass die arme Dönhoff erbittert in meinem Zimmer im Gartenhause in Charlottenhof wohnen muss. Die Königin hat sich heute morgen ein rendez Vous mit beiden Sachsen Königinnen gegeben zu einer sonderbaren sich gegenseitig längst verheissnen Feier des hundertjährigen Geburtstags eines Toten[,] des gemeinsamen Vaters, König von Bayern.” (letter probably dated May 27, 1856, Humboldt 2023, 452).

19 For the so-called diplomatic reports, see Péaud 2015.

20 “Ich ging gleich frühstücken im Café de Foy, dann zu Arago den ich sehr genesen gefunden und täglich zwei Mal besuche, dann in die Gesandschaft […] Ich habe heute am 2ten Tage gefühlt, was es heisst 23 Jahre einst an einem Orte gewohnt zu haben. Mir ist als hätte ich Paris nie verlassen, ich kenne jeden Stein, dazu lebe ich seit 1827 von wo an ich nur ruckweise hier bin, immer in denselben Zimmern, in denselben Meublen. Das Leben ist hier so freundlich leicht und unbeschreiblich unabhängig, wenn man lange in Berlin, das Adresscomptoir der Welt gewesen ist. Heute morgen habe ich bei Guizot gefrühstückt, wo die uralte Mutter einen liebenswürdigen Eindruck macht.” (letter dated October 14, 1847, Humboldt 2023, 231).

21 “Ich kann, theureste Gabriele, Dir nicht lebhaft genug danken für Deinen nie zu langen Brief, voll Herzlichkeit und Anmuth der Gefühle wie des Ausdrukkes. Das menschliche Leben, wenn es nicht grosse Leiden bringt, besteht aus einer Reihe kleiner Vorfälle die sich einer den anderen bedingen und wenn man sie niederschreibt od[er] einem Abwesenden erzählen soll, so hält man für uninteressant, was doch in der Verkettung und in der Sicherheit, dass nichts Furchterregendes am Horizonte steht, Freude erregt. Diese Freude bereitest Du mir, meine Theure, wenn Du mir von Bülows geschäftigem Wohlsein, von Deinen li[e]ben Kindern, dem schönen Enkel und den Erfurtern schreibst. Mit den politischen Begebenheiten ist es beinah eben so, es ist eine Art von Kleinleben in dem man den Glauben an grosse Dinge verloren hat, wenn man sich auch immer irgendwo in dem sogenannten friedlichen Europa blutig schlägt […].” (letter dated April 1, 1845, Humboldt 2023, 173).

22 “alte Froschkeulen, den Katzenbrei bayrischer Nudeln und die Petersilien-Suppe, eine historische Flüssigkeit, schmatzend verschlürfte und mit allen Tellern klapperte.” (letter dated May 5, 1848, Humboldt 20823, 182).

23 “Was dies mir so erwünschte Kommen betrift so habe ich Werther darüber sehr angelegentlichst sondirt aber wenig Befriedigung erhalten. Er meint: Bülow könne diese Möglichkeit besser als er voraussehen; er (Werther) glaube aber so stark an baldigen und wirklichen Abschluss der Belg[ischen] Angelegenheiten, dass er besorge, die Abreise könne | 2 | nicht vor Ende Sept[ember] od. Anfang October eintreten. Käme eine Unterbrechung der Negociation, dann freilich wäre es anders.” (letter presumably July 29, 1838, Humboldt 2023, 73).

24 “Bei dem König Louis Philip[pe] hatte ich im Cabinett eine lange Audienz: er war wie gewöhnlich, sehr freundlich, voller Lobeserhebung von Bülow’s Talent und viel gerühmter Liebenswürdigkeit. Da ich den Auftrag hatte, ihn zu erinnern, nicht aus Geldliebe für Leopold neue Schwierigkeiten zu machen, so ging er tief in die Belgische Sache ein, lies[s] mir aber leider! den Eindruk, er halte es noch für möglich, die Theilung der Schuld günstiger für Belgien zu machen […]: König Leop[old] wäre ohnedies sehr unpopulär wegen der Cession des Territoriums, solle er 20 Mill[ionen] francs jährlich zahlen so wäre dies ¼ des ganzen Einkommens … Ich antwortete dass als Fr[ankreich] und Belgien die 24 Art[ikel] unterschrieben, sie damals die Ausführung und Zahlung für möglich gehalten hätten und Belgien sei seit jener Epoche durch Handel reicher, nicht ärmer geworden; viele Staaten (Frankreich selbst, England[,] Preussen, Oestreich) hatten ¼ des Einkommen[s] auf die Zinsen zu wenden.” (letter dated August 25, 1838, Humboldt 2023, 75–76).

25 “Theure Gabriele. Die Belg[ischen] Nachrichten (der Zeitung) würden mir misfallen wenn nicht Bülow’s Brief und W. Russels hiesige gleichlautende und bisher sichere Nachrichten das nahe Ende verkündigten […] Mein Schnupfen entwikkelt sich wie die belgische Sache […].” (letter probably early 1839, Humboldt 2023, 79).

26 “Lord Palmerston hat Dich auf die gehässigste Weise hier denuncirt wegen verpönter Verbindung mit den Franzosen. Ich komme so eben von Charlottenburg zurük, wo ich die Denunciation dem König in seinem Cabinett vorgelesen. Er hat sie mit Verachtung angehört, rechtfertigt Dich vollkommen und will Dir Genugthuung verschaffen. […] Es sei dem König berichtet worden, dass […] William Russell in einer ungeheuren Aufregung gefunden, weil sich L[ord] Palmerston bitter über Dein Benehmen, über Vorschläge die Du […] solltest einseitig gemacht haben, beschwerte. Der König hatte die Nachricht davon so eben […] erfahren, lachte darüber […].” (to Heinrich von Bülow, November 24, 1840, Humboldt 2023, 111).

27 “Meine bittere Betrachtung über englische Staatsmänner ist diese: sie sprechen ewig von ihrer Loyautät und religiös-moralischem Gefühle, die Freundschaft die sie anderen Staatsmännern des Continents erzeigen ist die welche die Vornehmeren gegen Untergeordnete hegen. Sie erlauben sich alles so wie etwas selbständiges ihnen entgegen tritt, dann werden sie insolent, weil wir Völker des Continents zu einer inferieuren Menschenrace gehören. Auch politische Freiheit brauchen wir nicht, das ist eine Frucht die nur dem englischen Boden entspringen kann, nur dem engl[ischen] Volke gehört.” (letter of November 27, 1840, Humboldt 2023, 110–111).

28 “Ich schreibe wieder, Ihr Lieben, nicht bloss zu sagen dass ich wohl bin und ausgehe, nicht auch, um Dir Nachrichten zu geben, die jezt aus der Köllner Zeitung schon in die Staats Zeitung gekommen sind: ich schreibe weil besonders seit heute mir sehr traurig ums Herz ist. Die tolle Republik declarirt, Arago der bisher gar nicht genannt war u. bei keinem Banket sich befand, heute an der Spize der provisorischen republikanischen Regierung, die arme Herzogin mit ihren beiden Kindern zu Fuss in die Deputirten Kammer eindringend um sich als Regentin zu zeigen, dort verhöhnt, gröblich behandelt zur Flucht gezwungen; Blutvergiessen mehr als in den Julitagen; die Tuilerien verwüstet nach zweistündigem Gefechte und nachdem auf den König, die Herzogin und [ihre] Kinder die sich auf dem Balcon gezeigt, gefahrvoll geschossen! Der König scheint nach Laeken bei Brüssel geflüchtet von der Herzogin glaubt man, sie sei noch in der Nähe von Paris verstekt. […] Die Erklärung der Republik der ich kurze Dauer prophezeie, die aber wegen der strengen Urtheile über meinen Freund mich sehr unglüklich macht und wahrscheinlich zum Kriege führt, reizt u. exaltirt hier alles, um von zeitigem und würdevollem Nachgeben in ständischen Verhältnissen noch mehr zu entfernen.” (letter dated February 29, 1848, Humboldt 2023, 247).

29 “Ich komme von dem Leichenzuge. Ich habe nie eine grössere Ordnung und Ruhe in einer ungeheuren Menschenmasse erlebt. Nicht ein unanständiger Laut, kein politisches Wort, wie man dergleichen gefürchtet. Der König wünschte, dass man mitgehen sollte. Ich schloss mich den Studenten an, ging neben dem Prorector Johannes Müller und wurde von dem Publicum überall sehr freundlich behandelt. Wir waren um halb ein Uhr auf dem Gendarmen Markte wo an dem Kirchenportale 173 Särge standen: dazu kamen 50 mehr aus der Werderschen Kirche. Die Familien der Verstorbenen, schluchzende Bräute, viele sehr kleine Kinder … waren herzbrechend zu sehen – Ein Zug von wohl 5–600 Personen. Sidow’s [der Theologe K. L. A. Sydow] Rede bei den Särgen schien sehr kalt. Er hatte wahrscheinlich alle politische Anspielung vermeiden wollen, also ward (so viel ich vernahm) der König, der sich gestern so schön und muthvoll gezeigt, nicht genannt. Dann Reden von wahren und Deutsch-Catholiken, auch ein Rabiner. Der Leichenzug ging in zwei langen Zügen. Der König soll jedesmal auf das Balcon getreten sein, wenn die Särge kamen: ich sah es nicht, weil die Universität durch die Leidtragenden von den Särgen getrennt blieb. Ich blieb 3 ½ St[unden] auf den Beinen und verliess den Zug erst auf dem Alexanders Plaze.” (letter dated March 22, 1848, Humboldt 2023, 257).

30 “Hier ist troz der gewöhnlichen Heiterkeit des Königs (ich war gestern Abend noch in Charlottenburg) doch viel Noth mit der gedoppelten Unbequemlichkeit der Kaiserkrone wegen der Deputation von 33 Kurfürsten aus Frankf[urt] die erst den 2ten ankommen und wegen der Indiscretion der hiesigen Kammern die auch die Gesinnungen des Königs stärken wollen. Der König ist über dies alles so gereizt, dass er mir eher gestimmt schien gar niemand empfangen zu wollen. Die Minister werden aber schon mildern. Dass von Annehmen der Krone überhaupt keine Rede ist, brauche ich Dir wohl nicht erst zu sagen. Veto suspensif, Urwahlen, Grundrechte, sich aller Abstimmung enthaltende Gesandte von Baiern, Hanover, Wirtemberg, Sachsen. (Oestreich, das jezt so mächtige Oestreich, ungerechnet.[)] Man kann nicht aus den Händen derer empfangen die einen vorher beschimpft, denen man das Recht einseitig über das Kaiserthum zu disponiren nicht zugesteht. Aber es ist ein grosser öffentlicher Act, man kann ausschlagen, aber es muss mit Geschik und Würde geschehen, offen in einer praeparirten abgelesenen Rede. Zu dem allen habe ich wenig Vertrauen.” (letter of March 31, 1849, Humboldt 2023, 305).

31 “Nur einige Worte theure Gabriele. Die physische nicht die intellectuelle Besserung ist im Zunehmen. Ich war, weil es ein Mittel war die Königin in der Nähe zu sehen am heutigen, auf dem Schlosse nicht gefeierten Festtage, in die Friedenskirche gegangen. Die Königin hatte mich nicht gesehen aber man hatte es [ihr] wahrscheinlich [gesagt]. Sie hat bedauert, mich nicht angeredet zu haben und liess mir sehr freundlich sagen sie wolle mich allein nach Tische sehen. Sie war ganz allein, sehr traurig, für mich mittheilend, erzählend natürlich. Physische Besserung nehme zu nich[t] so das Intellectuell[e]. Er wisse nichts von seiner Krankheit und ihrer Dauer, keine Erinnerung von Aderlass, keine vom Kaiser von Russland; er glaubt ihn nur im vorigen Jahre gesehen zu haben, er klagt sich nicht deutlich ausdrücken zu können, erfindet unverständliche, selbsterfundene Worte! weiss die Namen zu finden, als zusammen hängende Phrasen; er fühlt sich sehr gequält u. immer traurig. Einmal da er sich allein glaubte rief er aus: Gott erbarme sich meiner. Er hat das Bewusstsein seiner Geistesschwäche. Er hat keine Lähmung er war heute aufgestanden und auf Minuten in das Zimmer der Königin gekommen. Das ist alles rührend und tief schmerzlich.” (letter probably dated October 15, 1857, Humboldt 2023, 487).

32 “Ich schreibe, theure Gabriele, was Du vielleicht schon weisst […] Gestern glaubte die Königin dem König die Vollmacht zur interimistischen Geschäftsführung vorlegen zu können zur Unterschrift. Er war lange schwieriger und sagte (was völlige Besinnung anzeigte[)]: ‘ich werde es mir überlegen‚. Die Königin sagte: ich werd[e] Dir nicht mehr davon sprechen bis Du Selbst es weisst. Heute Freitag erklärte er sich entschlossen und unterschrieb. Pr[inz] v. Pr[eußen], P[rinz] Carl und Manteuffel waren im Zimmer. Der König schien sie aber nicht zu bemerken.” (letter probably dated October 23, 1857, Humboldt 2023, 488).

33 “Ich habe einen langen langen Brief von Bonpland aus Montevideo. Er ist 76 Jahre alt, sehr kräftig und wohlhabend. Er hat so viel Vieh, dass er durch Einfälle der Indianer in einem Jahre 19000 Schafe, Rinder und Pferde hat verlieren können. Er spricht von Orangenbäumen seines Garten[s] deren einer 5 bis 6000 Früchte alle Jahr giebt – und doch will er nachdem er 30 Jahre in diesem paradisischen Klima lebt, nach Frankreich zurük. Es wird wohl bei dem thörichten Wunsche bleiben.” (letter dated February 8, 1850, Humboldt 2023, 337).

34 “Scheint mir eine Anwandlung von Lateinisch in der ich nur erusco lesen kann das nichts heisst: erubisco heisst ich erröthe […]! Aber das böse Cac…“ (Hedemann to Humboldt, June 21, 1851, Humboldt 20823, 373).

35 Lat.: By the way, I think that Carthage should be destroyed.

36 “Das alte Sprichwort sagt: / Der Mensch ist ein gehezter Hund / wird alt wie die aegyptische Kuh / und nimmt von Tage zu Tage zu / Worin er zunimmt sagt das Sprichwort nicht. Ich sage, in Correspondenz.” (letter probably written October 24, 1857, Humboldt 2023, 489).