Alberto Gómez Gutiérrez

Alexander von Humboldt has been praised and criticized throughout history depending on different readings and interests. The account of his encounters during his American voyage can shed light on the foundations for criticism and praise. This essay addresses the critical attitude of the botanist and astronomer Francisco José de Caldas towards Alexander von Humboldt in the years 1801 to 1803.

Alexander von Humboldt ha sido exaltado y criticado a través de la historia en función de lecturas e intereses diversos. La relación de sus encuentros en el curso de su viaje americano puede dar luces sobre el fundamento de las críticas y los elogios. Este ensayo aborda la actitud crítica del botánico y astrónomo Francisco José de Caldas hacia Alexander von Humboldt en los años 1801 a 1803.

Alexander von Humboldt a été loué et critiqué tout au long de l’histoire, en fonction des lectures et des intérêts particuliers. Le récit de ses rencontres lors de son voyage en Amérique peut éclairer les fondements des critiques et des éloges. Cet essai traite de l’attitude critique du botaniste et astronome Francisco José de Caldas à l’égard d’Alexander von Humboldt dans les années 1801 à 1803.

The invention of Humboldt1, a recent publication compiled by Mark Thurner and Jorge Cañizares-Esguerra, included the critical considerations of 13 historians on the geopolitics of knowledge in the times of Alexander von Humboldt. This book argues against the idea of an invention of nature attributed to the Prussian by Andrea Wulf in her biographical work.2 In the words of the editors: “Humboldt did not ‘invent nature’, nor did he pioneer globalization. Instead, he was the direct beneficiary of Iberian globalization and natural science”: “at every step the Prussian relied on the knowledge, networks, and archives of Spain and Hispanic America”3. To reinforce the significance of their title the editors point out that, in any case, one usually invents oneself during one’s own life, and Humboldt was no exception to this rule, rather an emblematic case as has been shown recently by Renner, Päßler and Moret in their assessment of Humboldtian biogeography under an explicit title: “‘My reputation is at stake’. Humboldt’s Mountain Plant Geography in the Making (1803–1825)”4.

Moreover, one of the four meanings of the dictionary of the Real Academia Española for “Invención” is “decepción, ficción”. The British Oxford Dictionary, on the other hand, includes seventeen meanings for this same noun, eventually indicating that there are more ways of inventing in English. Among these, there is an equivalent meaning for the Spanish definition: “a fabrication, fiction, figment”. An invention consists then not only in the discovery and development of an idea or an instrument, but also in a deception, a fiction, as it will be shown in the following examples of Humboldt’s interactions with the Neogranadian naturalist Francisco José de Caldas.

In addition to this etymological consideration, the concept of the heroic “inventor” should also be deconstructed, as has already been done in the field of Evolution with Charles Darwin and Alfred Russel Wallace, and as I have personally attempted with Humboldt’s “Wallace” in the field of Equatorial Biogeography5, namely Francisco José de Caldas, who reached the same scientific conclusions as Humboldt, at the same time, by different approaches6. In his Introduction to a North American translation of Humboldt’s Essai on the geography of plants, Stephen T. Jackson has argued that the Creole biogeographer Francisco José de Caldas had a significant influence on Alexander von Humboldt’s “decision to use the Andes as the ideal region to illustrate his ideas”7, and I have presented evidence implying that, in the Andes, both Caldas and Humboldt participated in the founding of the new science of biogeography, and that “the self-taught Neogranadian naturalist, mathematician, and geographer who upon his appointment to Mutis’s Real Expedición Botánica met Humboldt in the first semester of 1802, is conspicuously absent from all of Humboldt’s explicit references to previous or simultaneous biogeographic works”8.

In an article first published in 1960, the Catalonian geographer Pablo Vila i Dinarès criticizes Humboldt’s disregard of Caldas, noting that “el Barón debió darse cuenta de que aquel criollo se hallaba en el camino de establecer las relaciones existentes entre las plantas, su temperatura y la altitud, lo cual no dejó de sorprenderle [the Baron must have realized that the Creole was on the way to establish the existing relationships between plants, temperature, and altitude, which did not cease to surprise him]”. “Both”, says Vila referring to Humboldt and Caldas, “were found in the course of the same geobotanical studies”9. More than fifty years after, in 2016, I elaborated on Alexander von Humboldt and his transcontinental cooperation in the Geography of Plants, with an updated appreciation of the phytogeographical work of Francisco José de Caldas10.

The perception of the findings and accounts of naturalist travellers has varied according to who receives them, more or less critically, and according to who refers to them. The case of Humboldt is, once more, emblematic, and has already been studied by Nicolaas Rupke in his metabiographical work11 on the perception of the life and work of the Prussian by different social groups. As Rupke himself has asked in a more recent elaboration on successive biographical approaches to Humboldt since the second half of the 19th century, “Can we have ‘lives after death’, that is, a plurality of biographical Humboldts, suited to distinct times, places and concerns and yet, for each of them, lay claim to authenticity?”12. Furthermore, as Vera Kutzinski pointed out in her 2010 article on Alexander von Humboldt’s Transatlantic Personae: “Since the nineteenth century, Humboldtian avatars have been constructed to shore up all sorts of discourses and, at times, have been deployed even for opposed political causes”13. Caution must then be exerted while interpreting Humboldt’s life and works, and primary sources of the writings and impressions of his contemporaries should illuminate the real Humboldt, including his eventual dark face, often neglected on behalf of his heroization.

The first debate on the invention of Humboldt from a post-modern perspective14 took place in 2019 at FLACSO’s premises15 in Quito, Ecuador, and brought together again a group of historians on December 7, 2023. One additional debate took place in Cartagena, Colombia, at the end of 2019 at the Seminar on Humboldtian Studies coordinated by the Colombian Academy of Exact, Physical and Natural Sciences near the mud volcanoes of Turbaco. On that occasion, the German historian Sandra Rebok16 focused her critical assessment of Jorge Cañizares-Esguerra’s talk on “La invención de Humboldt”, interpreting it as a critique of Humboldt: Rebok objected to a possibly intentional judgement of the Prussian, as she stressed in her own talk the overvalued or undervalued perceptions of Humboldt in Iberoamerica, proposing that “hay que ser consciente de que estas interpretaciones a veces son fruto de una larga tradición de ‘lecturas intencionadas’ de Humboldt, en una multitud de contextos distintos [One must also be aware that these interpretations are sometimes the result of a long tradition of ‘intentional readings’ of Humboldt in a multitude of different contexts]”17. But the point was not to overvalue or undervalue Humboldt, but rather to assess the overvaluation or undervaluation of several 21st century projections of the Prussian traveler, notably those based on his heroization by Andrea Wulf.

It should be stressed here that the projection of Humboldt as a hero by Andrea Wulf is her own affair. Like any author, she is free to focus on her own perspective, and Wulf writes particularly well for the global public: she is an international bestseller for a reason. Consequently, since the first meeting at the FLACSO seminar in Quito, I have tried to “de-Wulfise” this controversy. The issue is not Andrea Wulf: the problem today is the global overestimation of Humboldt as stated recently by Andreas Daum18, which uncritically positions an international bestseller as the only (I could say lonely) reference. At the other extreme, also problematic, is the risk of resorting to “purposive readings” of Humboldt, as stated in the works of Rupke and Kutzinski.

In Miguel Ángel Puig-Samper’s recent review of The Invention of Humboldt19, he posits a very improbable generosity of Humboldt towards Francisco José de Caldas, by “giving him the draft of the Geography of plants”20: Would not this gesture rather be, as I tried to show in my chapter in this book, clear evidence of Humboldt’s anxiety and eagerness to validate his work with José Celestino Mutis (1732–1808) – Humboldt’s main botanical contemporary reference in the New Kingdom of Granada – against Caldas’s parallel work on biogeography, while he was still travelling? This draft was significantly sent from Guayaquil to Santafé by way of Quito with the explicit instruction of Humboldt to the Marquis of Selva Alegre to deliver it through Caldas.

As I showed in Chapter 4 of The Invention of Humboldt, the Prussian dedicated this draft to Mutis, but the first printing in Paris of the Essai sur la Géographie des Plantes was finally dedicated to Antoine-Laurent de Jussieu and René Desfontaines, two botanical authorities in France. In the same year, 1807, the Essay was published in Tübingen in its German edition and dedicated instead to Johann Wolfgang von Goethe: Three different dedicaces are unusual in the history of science, and show a typical gesture of Humboldt seeking to position himself in each territory, namely New Granada21, France and his homeland.

Puig-Samper wrote: “It is evident that enlightened science already existed in Spain as well as in the Hispanic territories, and that in some cases parallel contributions to scientific knowledge were made by Creole authors such as Francisco José de Caldas – with whom Humboldt rivals, but is generous in giving him the draft of the Geografía de las plantas – or metropolitan authors such as Mutis, whom he acknowledged in several of his works and in the extensive biography of Joseph-François Michaud’s dictionary”22. Although Puig-Samper acknowledges the Humboldt-Caldas simultaneity that I support in my text – what he calls their “parallel contributions23” and I have called “scientific simultaneity”24 – he mistakenly assumes Humboldt’s generosity towards Caldas, overlooking my explicit argument: “Was Caldas ́ report from Otavalo (…) the stimulus that led Humboldt to configure and send his biogeographic profile of Chimborazo to Mutis via Caldas in February 1803?” (Figure 1)25.

Concerning Humboldt’s opportunism, Mark Thurner recently ascribed a positive value (and paradoxical irony) to his ambivalent forgetfulness: “Irónicamente, quizás la grandeza de la obra y archivo de Humboldt reside en su naturaleza derivativa y compiladora, pues en ella quedaron incrustadas las huellas de los que hicieron posible su ciencia [Ironically, perhaps the greatness of Humboldt’s work and archive lies in its derivative and compiling nature, for embedded in it are the traces of those who made his science possible]” (Thurner, 2023, 174).

Further critiques of Humboldt’s works in connection to local experts during his American voyage can be applied to: 1- The chronological succession of Humboldt’s geographical and biogeographical profiles; 2- Humboldt’s lies; 3- Caldas’s criticisms of Humboldt.

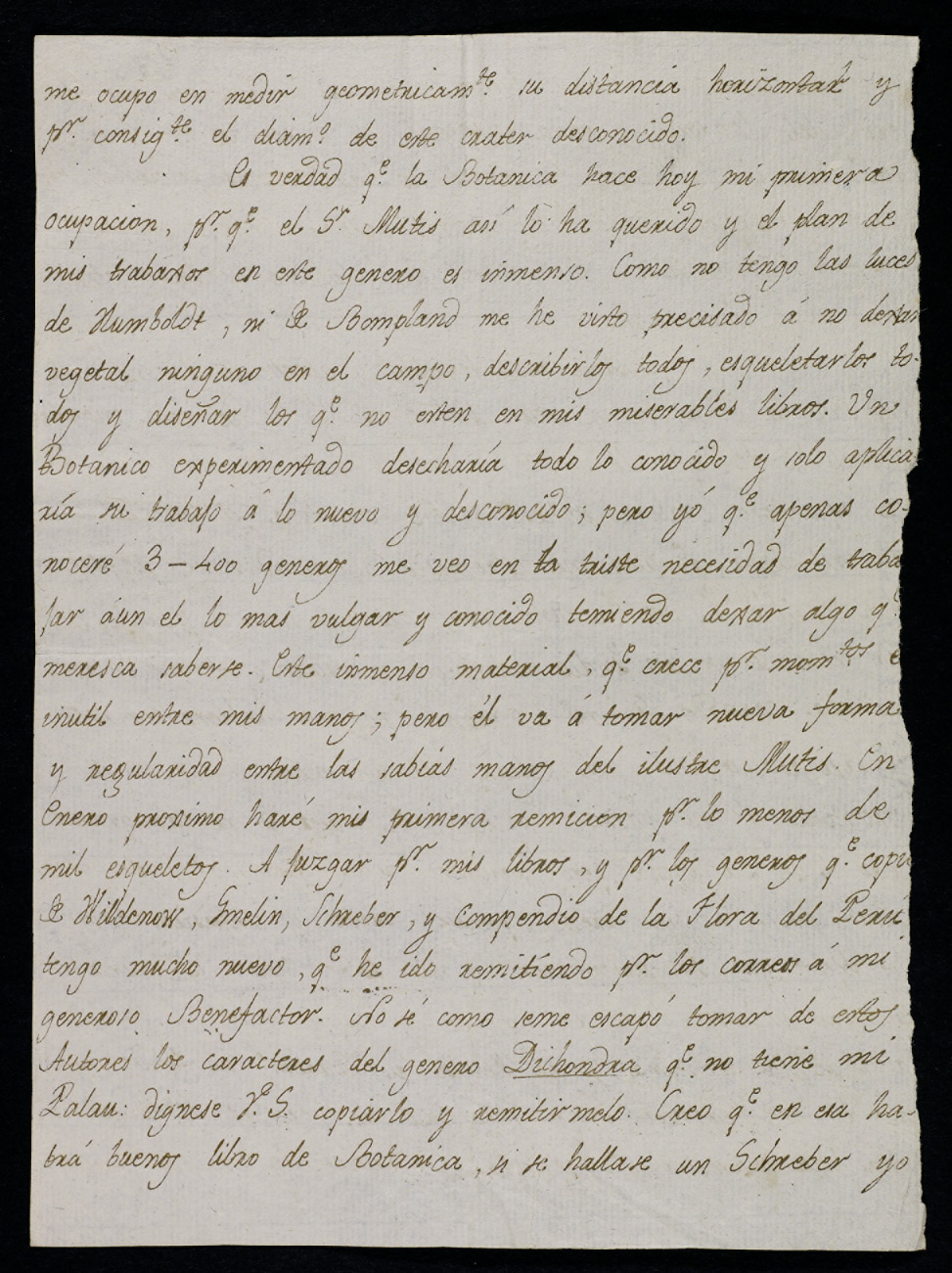

Fig. 1. Francisco José de Caldas. Letter to Alexander von Humboldt from Otavalo (1802). Caldas, F. J. (1802). Letter to Alexander von Humboldt from Otavalo on November 7, 1802. Tagebücher der Amerikanischen Reise VIIbb et VIIc, f. 475. Staatsbibliothek, Berlin. https://digital.staatsbibliothek-berlin.de/werkansicht?PPN=PPN779884310&PHYSID=PHYS_0927&view=overview-toc&DMDID=DMDLOG_0001.

Humboldt had been drawing up graphic levellings of some of the areas that he had travelled through from Spain onwards, but none of them contain biogeographical elements, neither plants nor animals26. His first properly biogeographical profile is that of Chimborazo, after dwelling with Caldas, and after having received his letter from Otavalo on November 17, 1802, in which Caldas told him that he was collecting plants at different altitudes on Imbabura, a local volcano27.

It should be also considered that those who knew the most about thermic floors and cultivation zones were the local landowners and peasants. The delimitation and understanding of these graded boundaries corresponded to the practical knowledge acquired and tested generation after generation. Without their collaboration, the schematization of that knowledge by either Humboldt or Caldas would have taken several years, since it involved a large set of plants. In other words, Humboldt’s and Caldas’ work on biogeography rested on a vast body of local knowledge, gathered through interviews and travels with intelligent guides. Caldas was the son of landowners and a close friend of the sons of landowners, and therefore had an undoubted advantage – which cannot be overlooked – over the Prussian. He had also travelled more in the territories of New Granada with repeated ascents and descents by mule to prove microclimatic modification. Another obvious advantage of Caldas is that he spoke better Spanish than Humboldt and could communicate comfortably with the locals. It is important, therefore, to highlight the preliminary existence of a popular knowledge on thermic floors and both wild and cultured plants in the New Kingdom, as established locally after successive trial and error experiments for several generations.

There is not enough space in this article to refer at length to what can be postulated as Humboldt’s lies or deceptions. I will only cite three examples, with their respective evidence: a- Mutis’s funding of Caldas’ eventual participation in Humboldt’s expedition; b- The history of the geography of plants referred to by Humboldt in 1826; c- The fate of the botanical plates that Mutis gave to Humboldt in September 1801.

a- Mutis’s funding of Caldas’ eventual participation in Humboldt’s expedition: José Celestino Mutis, the director of the Royal Botanical Expedition in New Granada, supported Caldas’s intentions to travel with the Prussian naturalist: “Your most ardent wishes will be fulfilled if my dearest Baron von Humboldt will give us his consent”28, and sent the corresponding money. However, in a letter from Caldas to Mutis dated in Quito on 6 April 1802, Caldas wrote that Humboldt himself, after denying that Mutis had informed him of his support for Caldas, finally confessed to him: “My friend, I have lied to you: Mr Mutis talks to me at length about the matter, but I, who have resolved to travel alone, did not want to give you this grief”29 (Note 1).

The fact that Humboldt lied to Caldas on his awareness of financial support by Mutis, clearly shows an intention – an explicit containment –, on his relationship with Caldas on grounds that should be further explored, possibly dealing with an implicit scientific contention. It is then particularly important to consider what geographer Vila i Dinarès suggested in his assessment of the scientific simultaneity of Humboldt and Caldas, “both were found in the path of the same geobotanical studies”30.

b- The history of the geography of plants referred to by Humboldt in 1826: Ten years after Caldas’s execution by the Spanish army in 1816, Humboldt finally referred to his work on plant geography, even if only in a preliminary prospectus for a book that was never published. In this 1826 prospectus, Humboldt included Caldas in a long list of 56 naturalists who had worked in the new field that Humboldt himself, and only he, would had pioneered: “During the last 15 years, [the following botanists] have dealt with questions relating to this science or have contributed materials that would extend its limits”31. But there is an unexpected mistake in this late acknowledgement, for Humboldt was a very precise quantifier and he was surely aware that Caldas had been working on botanical barometry since at least the beginning of 1802, meaning twenty-four and not fifteen years before 1826 (Figure 2). Moreover, Caldas had already published one scientific article in 1808 in his own journal, the Semanario del Nuevo Reyno de Granada, dealing with the biogeographical distribution of plants and animals in the Andes:

The middle region of the Andes (from 800 to 1,500 toises), with a mild and moderate climate (from 10° to 19° Réaumur), produces trees of some elevation, legumes, healthy vegetables, crops, all the gifts of Ceres; robust men, beautiful women of beautiful colours, are the heritage of this happy soil. Far from the deadly poison of serpents, free from the annoying sting of insects, its inhabitants roam the fields and forests in complete freedom. The ox, the goat, the sheep, offer them their offal and accompany them in their labors. The deer, the tapir (Tapirus L.), the bear, the rabbit, etc., populate the places where man’s empire has not reached.

The upper part (from 1,500 to 2,300 toises), under a misty and cold sky, produces nothing but bushes, small shrubs and grasses. Mosses, algae and other cryptogams put an end to all vegetation at 2,280 toes above the sea. Living creatures flee from these harsh climates, and very few dare to climb these dreadful mountains. From this level upwards they discover nothing but barren sands, bare rocks, eternal ice, loneliness and fog.32

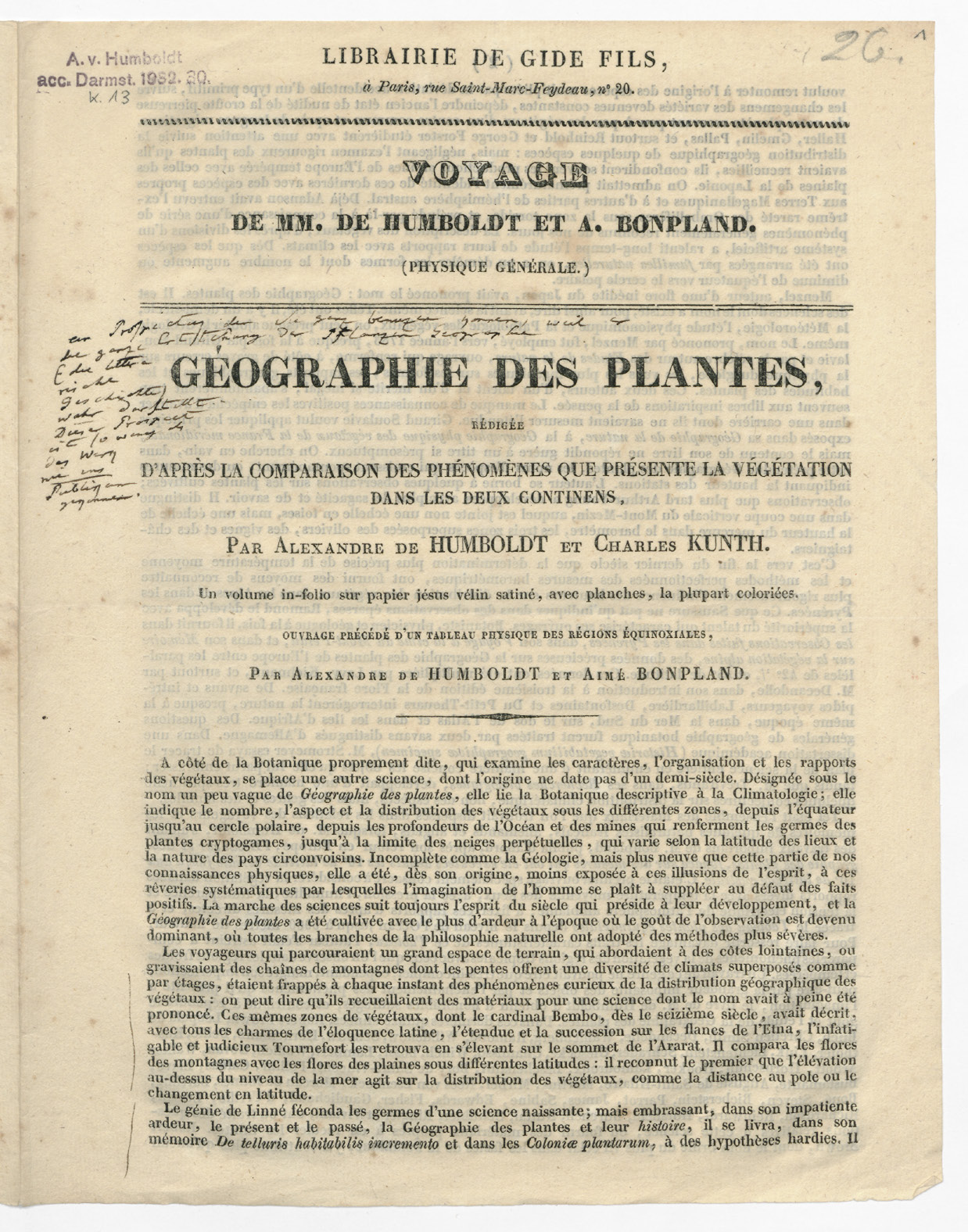

Fig. 2. Alexander von Humboldt and Carl Kunth. Géographie des plantes [Prospect]. Humboldt, A. & C. Kunth. (1826). Géographie des plantes [Prospect]. Staatsbibliothek zu Berlin Preußischer Kulturbesitz, Nachl. Alexander von Humboldt, gr. Kasten 13, Nr. 26, Bl. 1–2. https://digital.staatsbibliothek-berlin.de/werkansicht?PPN=PPN838243452&PHYSID=PHYS_0001.

In 1809 Caldas published in this same journal the complete Spanish translation of Humboldt’s 1803 manuscript on the geography of plants33, including a complete series of critical notes on Humboldt’s statements34. Surprisingly, not a single reference to Caldas and his work on phytogeography was included by Humboldt in his Essai sur la géographie des plantes in 1805–1807, only two lines on Caldas’ pioneering work on the use of boiling water in barometry35.

c- The fate of the botanical plates that Mutis gave to Humboldt in September 1801: In the chapter of The Invention of Humboldt entitled “An archaeology of Mutis’s disappearing gift to Humboldt”36, the Colombian historian José Antonio Amaya reviews in detail the history of the 107 botanical plates that Mutis gave to Humboldt and Bonpland in 1801, and that disappeared. Amaya found evidence that they were used – he says copied – for Plantes Equinoxiales. One of the references that this historian offers to support his interpretation, is a letter sent to Humboldt by Mariano Lagasca, who was the director of the Royal Botanical Garden in Madrid from 1813 to 1823 and in charge of the “installation, arrangement, conservation, inventory, study and publication attempt of Mutis’s Flora of New Granada”37. This work remained unpublished for nearly 1.5 centuries after the death of Mutis, until 1954, when the first illustrated grand folio volume (of 39 to date and at least 11 more in preparation) was released following an agreement of the Royal Botanical Garden in Madrid and the government of Colombia38. Lagasca was straightforward:

I close this letter, assuring you that I am firmly persuaded that several of the plant drawings you published in Plantae aequinoctiales and Monographia Melastomae et Rhexiae are copies of those of the Flora de Bogotá, although generally more or less cropped to accommodate the dimensions of the work.39

The plates of the Botanical Expedition were the property of the Spanish Crown, but Mutis gave away a hundred of them as gifts for Humboldt and Bonpland with an intention that is not easy to specify. Humboldt, as is known, offered them to the professors of the Institut in Paris, and it is very unfortunate that, as it is assumed that he did send them to Paris, they have to this date not been found, neither in the archives of the Jardin de Plantes nor in any other archive (public or private) in France or in the world. Amaya’s point is that these plates were “copied” and used in the printed botanical works of Humboldt and Bonpland without any due acknowledgement of the original authors. A similar “appropriation” has been suggested for a Mutisian zoological plate representing an endemic fish of the Bogotá River, Eremophilus mutisii, albeit with an explicit epithet40.

Caldas reported at least one significant third-party criticism of Humboldt’s character:

I think my moderation has changed his mind: I am not quite sure on this point. But this very day a friend came into my house and said to me: “Do not trust the Baron: I have heard him say to N., to N. (ignorant young men and the same I have spoken of), Caldas is a fool, and other things of that kind”. I do not want to believe it at present. For you hardly know my inner self, and this town is abundant with gossip.41

This criticism can explain the reluctance of Humboldt to allow Caldas to accompany him, as Caldas himself told Mutis in a subsequent letter from Quito on April 21, 1802:

I owe you the comparison of our characters and the most frequent occasions of difference. Monsieur le Baron judges me severe, inflexible, sad; how can I approve without becoming an accomplice; how can I reprove by showing a laughing countenance? This is the origin of the aversion, if one can call it that, of the dislike which Monsieur le Baron has for my company; this is the origin of his refusal, whatever he may say.42

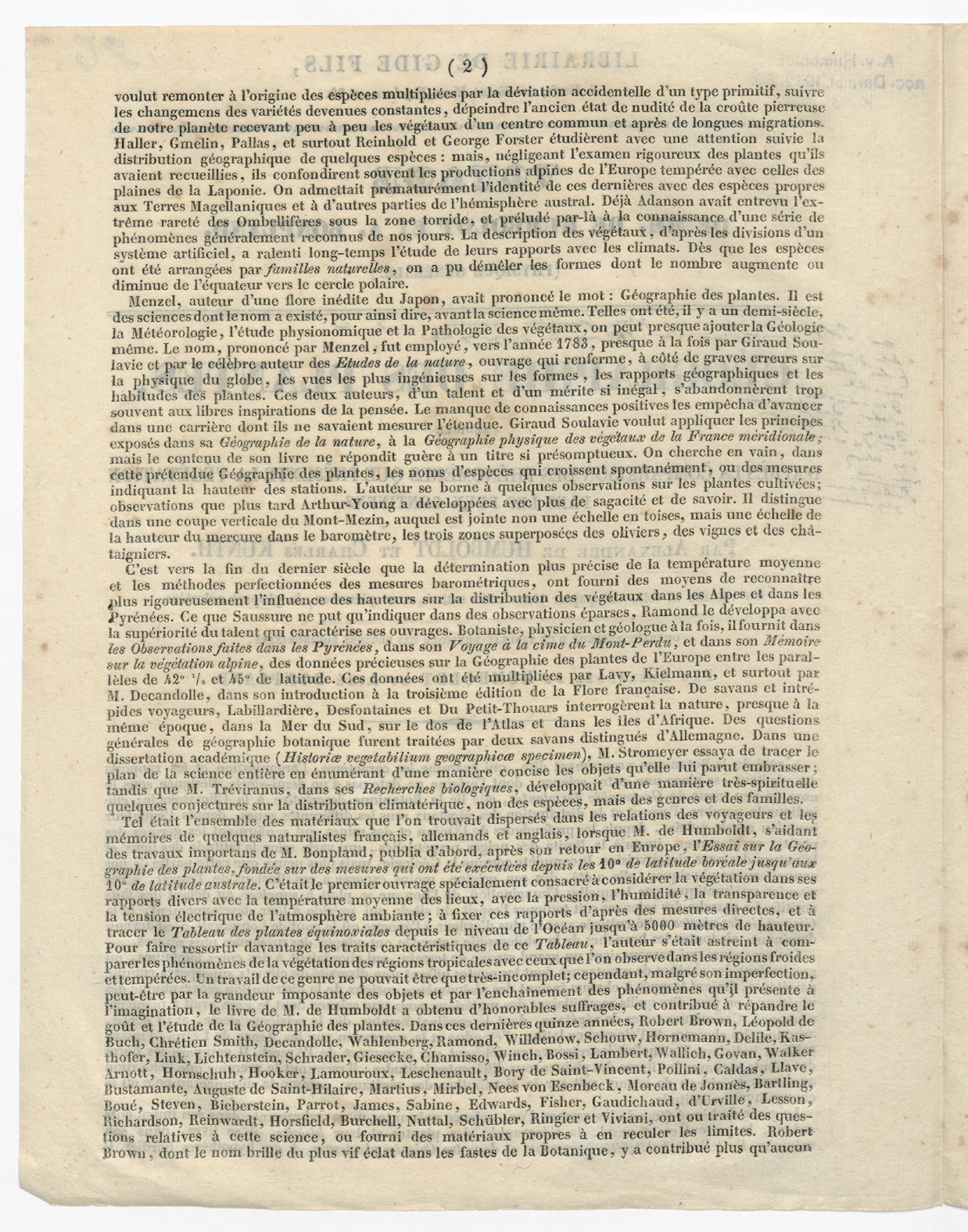

One more negative consideration of the astronomic measurements of Caldas (specifically regarding his own astronomic measurements) can be found in an undated manuscript note of Humboldt’s in an unpublished geographical profile drawn by Caldas before 1801, in which Caldas referred for Santafé a longitude of 75o 11' “del Observatorio de París” and a latitude of 4o 10' (Figure 3): “Par Mr Caldas. L’echelle en latitude est fausse, car la lat. de Santa Fe est 4o 35' 48''”.

Fig. 3. Francisco José de Caldas [and Alexander von Humboldt] (c1802). Humboldt, A. [& F. J. Caldas, F. J.] (no date). Mapas y Apuntes: Colombia y Venezuela. Archivo Histórico, Biblioteca de Cultura y Patrimonio, Quito, Ecuador, Fondo Jacinto Jijón y Caamaño, JJC-0001.2505.14.

Even if Humboldt criticized Caldas’s character and measurements, one must consider his paradoxical scientific appraisals and positive comments on his work. Two good examples of his positive comments were:

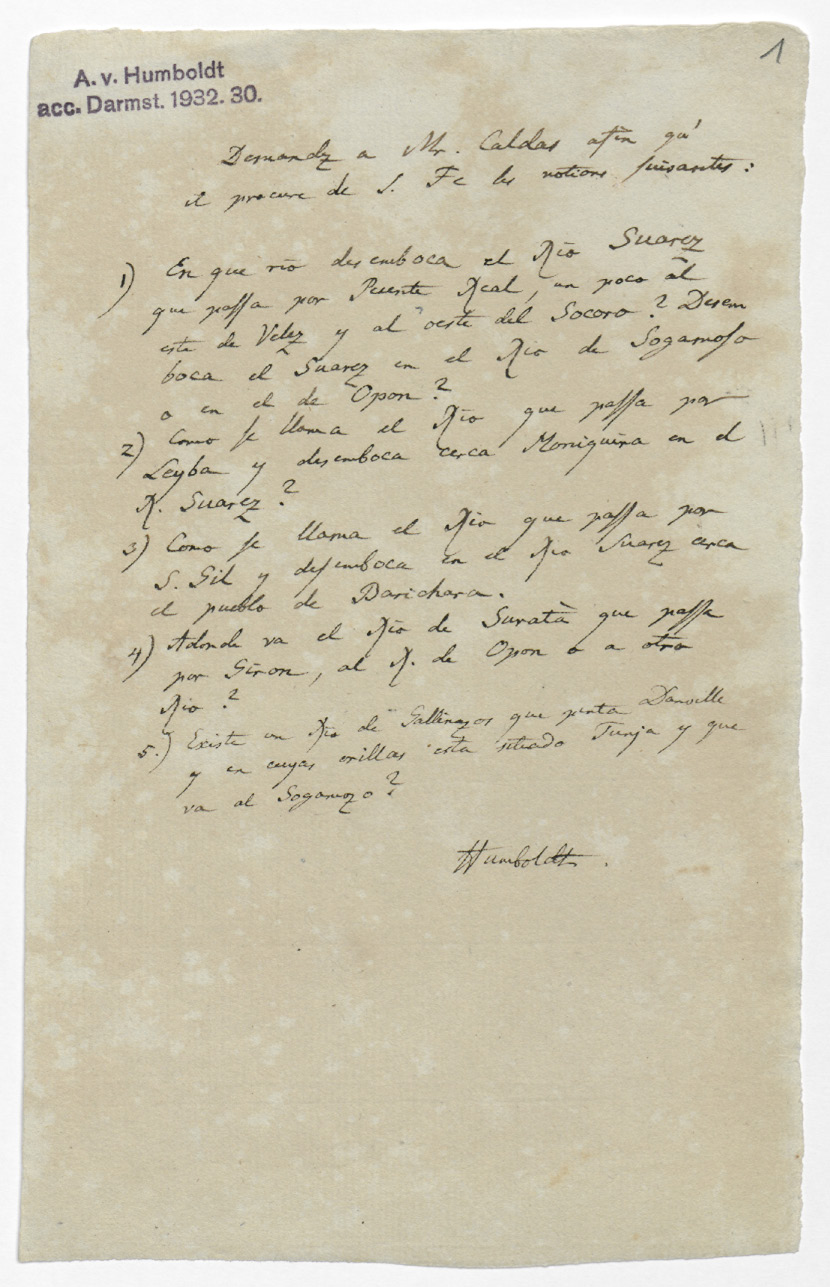

Ask Mr Caldas to give you the following [geographical] notions45:

Fig. 4. Alexander von Humboldt. [Questions to be asked to Caldas] (c1815). Humboldt, A. (c1815). Aufzeichnungen und Notizen zu Südamerika. Staatsbibliothek zu Berlin Preußischer Kulturbesitz, Nachl. Alexander von Humboldt, kl. Kasten 7b, Nr. 47a, Bl. 1–21 und 25–27. https://digital.staatsbibliothek-berlin.de/werkansicht?PPN=PPN78798096X&PHYSID=PHYS_0001&view=picture-single.

One might be critical, or even skeptical, of Caldas’s criticisms and their impact on his relationship with Humboldt in the first half of 1802, which probably determined that Humboldt did not travel further with him on his American expedition and accepted instead the company of Carlos Montúfar47. As a reference, I will only list here four of Caldas’s criticisms of the Prussian related to: a- The accuracy of Humboldt’s thermometer; b- A taxonomic competition; c- Cartography; d- Intellectual espionage. For the original criticisms of Humboldt’s thermometer, of taxonomic competence and of Humboldt’s cartography, please see notes 2–5 at the end of this text, which offer direct evidence for specific Caldasian critiques.

Concerning intellectual espionage, as an eventual cause of distance between Humboldt and Caldas, I argue that Humboldt could have been aware of Caldas intentions to follow and observe his works and proceedings, as Jorge Juan and Antonio de Ulloa had done about Charles de la Condamine’s previous equatorial expedition. Indeed, Caldas asked his friend Santiago Arroyo, based in Santafé, to endorse his participation in the expedition of Humboldt and Bonpland just as Juan and Ulloa had been appointed to participate in the previous French expedition to the Equator arranged by the Spanish Crown: “You know that Ulloa and Juan could not, when they came to America, stand alongside Godin, Bouguer and La Condamine; but they returned to Europe worthy of a place in the Academy of Sciences. You flatter me when you imagine that I could accompany these scholars and play the role of Ulloa for them: I do not find myself capable of fulfilling the confidence of the nation in the event [of] that taking place”48. But of course, Humboldt was travelling on a voyage financed by himself and did not want any spies.

Before concluding, and as proof of the estrangement that resulted from their respective attitudes, I will cite one of Caldas’ own claims against Humboldt in a letter written to his uncle Manuel María Arboleda in 1802: “What a monster, what a colossus of enlightenment and generosity is [José Ignacio de] Pombo in Cartagena! Let us be proud to have such a compatriot. Someday Caldas, this Caldas, oppressed and despised by the ungrateful Humboldt, will know how to reward with dignity such a virtuous and illustrious compatriot, will know how to forgive Humboldt”49.

With these considerations and references to early manuscript sources of Francisco José de Caldas in which he commented upon Humboldt and his endeavors, it can be concluded that the Neogranadian was one of Humboldt’s first critics. The critical attitude of Caldas, whom Humboldt would not accept as a travelling companion, might be interpreted as one-sided. However, as historian Ulrich Päßler noted after reading a preliminary version of this text, the opinions of Caldas should not be understood as “a moral judgment on Humboldt, in a story in which one side is simply the exploiter and the other the exploited”50, but rather analyzed in order to underline some aspects and relevant details of Humboldt’s academic self-representation, and properly define the knowledge networks he created, preceding the subsequent fabrication of further academic networks centered on him, in what has been called, indiscriminately, Humboldt’s science and Humboldtian science51.

I am indebted to Frank Holl, Tobías Kraft, Ulrich Päßler, Florike Egmond, Peter Mason, Daniel Gutiérrez, Georges Lomné and Sergio Mejía, for critically reading a first draft of this text. Georges Lomné, Sergio Mejía and Santiago Cabrera Hanna were particularly timely as they provided key primary documents related to Humboldt and Caldas retrieved from the Archivo Histórico – Biblioteca de Cultura y Patrimonio in Quito, Ecuador. This article was written as a synthesis of successive discussions over the Humboldt-Caldas relationship in the past months with Mark Thurner, Jorge Cañizares-Esguerra and Uli Päßler.

Amat-García, G. & Agudelo-Zamora, H. D. (2020): Las tareas zoológicas de la Real Expedición Botánica del Nuevo Reino de Granada (1783–1816). Revista de la Academia Colombiana de Ciencias Exactas, Físicas y Naturales 44 (170), 194–213, https://raccefyn.co/index.php/raccefyn/article/view/1016/2707.

Amaya, José Antonio (2023): An archaeology of Mutis’s disappearing gift to Humboldt. In: The invention of Humboldt. On the geopolitics of knowledge, edited by Thurner, M & J. Cañizares-Esguerra. New York and London: Routledge, 116–147.

Caldas, F. J. ([1801] 1917): [Letter to Santiago Arroyo, Popayán, May 20, 1801]. In: Cartas de Caldas, edited by Posada, E. Bogotá: Academia Colombiana de Historia, 49–52, https://babel.banrepcultural.org/digital/collection/p17054coll10/id/4076.

Caldas, F. J. (1802): [Letter to Alexander von Humboldt from Otavalo on November 17, 1802]. Tagebücher der Amerikanischen Reise VIIbb et VIIc, f. 475. Staatsbibliothek, Berlin, https://digital.staatsbibliothek-berlin.de/werkansicht?PPN=PPN779884310&PHYSID=PHYS_0927&view=overview-toc&DMDID=DMDLOG_0001.

Caldas, F. J. ([1802] 1917a): [Letter to José Celestino Mutis, Quito, April 6, 1802]. In: Cartas de Caldas, edited by Posada, E. Bogotá: Academia Colombiana de Historia, 146–152, https://babel.banrepcultural.org/digital/collection/p17054coll10/id/4076.

Caldas, F. J. ([1802] 1917b): [Letter to José Celestino Mutis, Quito, April 21, 1802]. In: Cartas de Caldas, edited by Posada, E. Bogotá: Academia Colombiana de Historia, 152–158, https://babel.banrepcultural.org/digital/collection/p17054coll10/id/4076.

Caldas, F. J. ([1802] 1966): [Memoir on the origin of the system of measuring mountains and on the project of a scientific expedition Quito, 1802]. In: Obras Completas de Francisco José de Caldas, edited by Bateman, A. D. Bogotá: Universidad Nacional, 293–302, https://repositorio.unal.edu.co/handle/unal/2065.

Caldas, F. J. ([1802] 2016a): [Letter to Manuel María Arboleda, Otavalo, November 7, 1802]. In: Caldas ilustradas, edited by Savitskaya, N. & Caldas Varona, D. Bogotá: Universidad Distrital Francisco José de Caldas/Academia Colombiana de Ciencias Exactas, Físicas y Naturales, 388–390.

Caldas, F. J. ([1802] 2016b): [Essay of a memoir on a new method of measuring mountains by thermometer, Quito y abril 1802]. In: Ensayo de una memoria sobre un nuevo método de medir las montañas por medio del termómetro. Francisco José de Caldas 1768–1816. Bicentenario de su muerte, edited by Valencia Restrepo, D. Medellín: Universidad de Antioquia, 73–98.

Caldas, F. J. ([1802] 1849): [Memoir on the plan of a projected voyage from Quito to North America]. In: Semanario de la Nueva Granada, edited by Acosta, J. Paris: Antoine Lasserre, 546–567, https://catalogoenlinea.bibliotecanacional.gov.co/client/es_ES/search/asset/118820.

Caldas, F. J. (1808): Notas del Editor [a la Geografía de las plantas de Alexander von Humboldt]. Semanario del Nuevo Reyno de Granada 1–6: 1–49, https://babel.banrepcultural.org/digital/collection/p17054coll26/id/1546.

Caldas, F. J. (1809): Notas del Editor [a la Geografía de las plantas de Alexander von Humboldt]. Semanario del Nuevo Reyno de Granada 21–24: 163–189, https://babel.banrepcultural.org/digital/collection/p17054coll26/id/1622.

Daum, A. W. (2024): Humboldtian science and Humboldt’s science. History of Science May 21: 732753241252478. Epub ahead of print. PMID: 38770782, 1–23, https://journals.sagepub.com/doi/10.1177/00732753241252478.

Gómez Gutiérrez, A. (2016): Alexander von Humboldt y la cooperación transcontinental en la Geografía de las plantas: una nueva apreciación de la obra fitogeográfica de Francisco José de Caldas. HiN – Alexander von Humboldt im Netz. Internationale Zeitschrift für Humboldt-Studien 17 (33), 24–51, https://www.hin-online.de/index.php/hin/article/view/238.

Gómez Gutiérrez, A. (2018): Humboldtiana neogranadina Bogotá: CESA/Pontificia Universidad Javeriana/Universidad de los Andes/Universidad del Rosario/Universidad EAFIT/Universidad Externado de Colombia, 5 vols, https://bibliotecanacional.gov.co/es-co/colecciones/biblioteca-digital/humboldtiana/Documents/index.html.

Gómez Gutiérrez, A. (2021): Consideraciones en torno al primer artículo impreso sobre la geografía de las plantas de Alexander von Humboldt, publicado en La Habana en mayo de 1804. Revista de la Academia Colombiana de Ciencias Exactas, Físicas y Naturales 45 (177): 1192–1204, https://raccefyn.co/index.php/raccefyn/article/view/consideraciones-en-torno-al-primer-articulo-impreso-sobre-la-geo/3172.

Gómez Gutiérrez, A. (2023a): Caldas and Humboldt in the Andes: Who invented biogeography? In: The Invention of Humboldt: On the Geopolitics of Knowledge, edited by Thurner, M. & J. Cañizares-Esguerra. New York and London: Routledge, 76–115.

Gómez Gutiérrez, A. (2023b): Las invenciones de Humboldt y Caldas. Procesos. Revista Ecuatoriana de Historia 58, 175–178, https://revistas.uasb.edu.ec/index.php/procesos/article/view/4594/4397.

Gómez Gutiérrez, A. (2024a): Prehistoria del Observatorio Astronómico Nacional. Registros meteorológicos y astronómicos de José Celestino Mutis y Francisco José de Caldas entre 1772 y 1782. Revista de la Academia Colombiana de Ciencias Exactas, Físicas y Naturales 48 (186): 178–194, https://raccefyn.co/index.php/raccefyn/article/view/prehistoria_del_observatorio_astronoastr_nacional_registros_mete/3978.

Gómez Gutiérrez, A. (2024b): Humboldtiana neogranadina: Alexander von Humboldt’s personal contacts and natural relations in Colombia. In: Alexander von Humboldt. Die ganze Welt, der ganze Mensch. Baden-Baden: Olms, 109–132.

Gómez Gutiérrez, A. & J. G. Portilla (2021): Francisco José de Caldas: ¿avatar de Humboldt? Reflexiones en torno a cinco cartas anónimas publicadas en el Diario Político de Santafé de Bogotá en 1810. Revista de la Academia Colombiana de Ciencias Exactas, Físicas y Naturales 45 (175): 387–404, https://raccefyn.co/index.php/raccefyn/article/view/francisco-jose-de-caldas-avatar-de-humboldt-reflexiones-en-torno/3049.

Gómez Gutiérrez, A. & J. Hahn von Hessberg (2024): Alexander von Humboldt. Estudios Humboldtianos. Barranquilla: Universidad del Norte.

Hossard, N. (2004): Alexander von Humboldt & Aimé Bonpland. Correspondance 1805–1858. Paris: L’Harmattan.

Humboldt, A. [& F. J. Caldas, F. J.] (no date): Mapas y Apuntes: Colombia y Venezuela. Archivo Histórico, Biblioteca de Cultura y Patrimonio, Quito, Ecuador, Fondo Jacinto Jijón y Caamaño, JJC-0001.2505.14.

Humboldt, A. & A. Bonpland (1805–1807): Essai sur la géographie des plantes accompagné d’un tableau physique des régions équinoxiales […]. Paris: Levrault, Schoell et Compagnie, https://www.biodiversitylibrary.org/item/37872#page/3/mode/1up.

Humboldt, A. (1809): Geografía de las plantas o quadro físico de los Andes Equinoxiales, y de los países vecinos; levantado sobre las observaciones y medidas hechas sobre los mismos lugares desde 1799 hasta 1803 […]. Semanario del Nuevo Reyno de Granada 16–21: 121–163, https://babel.banrepcultural.org/digital/collection/p17054coll26/id/1617.

Humboldt, A. (c1815): Aufzeichnungen und Notizen zu Südamerika. Staatsbibliothek zu Berlin Preußischer Kulturbesitz, Nachl. Alexander von Humboldt, kl. Kasten 7b, Nr. 47a, Bl. 1–21 und 25–27, https://digital.staatsbibliothek-berlin.de/werkansicht?PPN=PPN78798096X&PHYSID=PHYS_0001&view=picture-single.

Humboldt, A. & C. Kunth. (1826): Géographie des plantes [Prospect]. Aufzeichnungen und Notizen zu Südamerika Staatsbibliothek zu Berlin Preußischer Kulturbesitz, Nachl. Alexander von Humboldt, gr. Kasten 13, Nr. 26, Bl. 1–2, https://digital.staatsbibliothek-berlin.de/werkansicht?PPN=PPN838243452&PHYSID=PHYS_0001.

Humboldt, A. et al. (1834): Carte du Rio Grande de la Magdalena, depuis ses sources jusqu’à son embouchure. Voyage de MM. Alexandre de Humboldt et Aime Bonpland. Atlas Géographique et Physique, pour Accompagner la Relation Historique. Paris: J. Smith, https://www.davidrumsey.com/luna/servlet/detail/RUMSEY~8~1~292872~90064417:XXIV--Carte-du-Rio-Grande-de-la-Mag?qvq=q:pub_list_no%3D%2212125.000%22;lc:RUMSEY~8~1&mi=47&trs=61.

Jackson, S. T. (2009): Introduction: Humboldt, Ecology and the Cosmos. In: Alexander von Humboldt and Aimé Bonpland. Essai on the geography of plants, edited by Jackson, S. T. Chicago: The Chicago University Press, 13–14.

Knobloch. E. (2023): Alexander von Humboldts Naturgemälde der Anden. HiN – Alexander von Humboldt im Netz. Internationale Zeitschrift für Humboldt-Studien 24 (47), 109–122, https://www.hin-online.de/index.php/hin/article/view/360/722.

Kutzinski, V. M. (2010): Alexander von Humboldt’s transatlantic personae. Atlantic Studies 7 (2), 99–112, https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/abs/10.1080/14788811003700209.

Mejía Macía, S. A. (2022): El Mapa de Timaná: versión de puño y pluma de Francisco José de Caldas. Revista de la Academia Colombiana de Ciencias Exactas, Físicas y Naturales 46 (179), 496–513, https://raccefyn.co/index.php/raccefyn/article/view/el_mapa_de_timana_version_de_puno_y_pluma_de_francisco_jose_de_c/el_mapa_de_timana_version_de_puno_y_pluma_de_ffrancisc_jose_de_c.

Moret, P., P. Muriel, R. Jaramillo, O. Dangles (2019): Humboldt’s Tableau Physique revisited. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences U.S.A. 116, 12889–12894.

Mutis, J. C. (1954–2024): Flora de la Real Expedición Botánica del Nuevo Reino de Granada (1783–1816); promovida y dirigida por José Celestino Mutis; publicada bajo los auspicios de los gobiernos de España y de Colombia y merced a la colaboración entre los Institutos de Cultura Hispánica de Madrid y Bogotá. Madrid/Bogotá: Ediciones Cultura Hispánica, 39/50 vols, https://bibdigital.rjb.csic.es/records/item/15840-flora-de-la-real-expedicion-botanica-del-nuevo-reino-de-granada?offset=1.

Päßler, U. (2024): Reise als Werk. Alexander von Humboldts Beobachtungen, Aufzeichnungen und Entwürfe zur Geographie der Pflanzen (1799–1804). In: Alexander von Humboldt. Die ganze Welt, der ganze Mensch. Baden-Baden: Olms, 79–108.

Puig-Samper, M. A. (2023): Book review: The Invention of Humboldt: On the Geopolitics of Knowledge. Hispanic American Historical Review 10942729, 147–149, https://doi.org/10.1215/00182168-10942729.

Rebok, S. (2019): Percepción de Humboldt en Iberoamérica: Retos y oportunidades de una temporada temática. Stuttgart: IFA-Edition Kultur und Außenpolitik, https://www.ssoar.info/ssoar/handle/document/62426.

Rebok, S. (2024a): Entre heroización, apropiación y crítica: problemas contemporáneos con la obra de Alexander von Humboldt. In: Alexander von Humboldt. Estudios Humboldtianos, edited by Gómez Gutiérrez, A. & J. Hahn von Hessberg. Barranquilla: Universidad del Norte, 56–69.

Rebok, S. (2024b): Es vuestro, pero también es nuestro’: distintas percepciones de Humboldt en Iberoamérica. In: Alexander von Humboldt. Estudios Humboldtianos, edited by Gómez Gutiérrez, A. & J. Hahn von Hessberg. Barranquilla: Universidad del Norte, 217–232.

Renner, S. S., U. Päßler, P. Moret (2023): ‘My Reputation is at Stake’. Humboldt’s Mountain Plant Geography in the Making (1803–1825). Journal of the History of Biology 56, 97–124, https://doi.org/10.1007/s10739-023-09705-z.

Rupke, N. A. (2005): Alexander von Humboldt: A Metabiography. Frankfurt am Main: Peter Lang.

Rupke, N. A. (2021): Humboldt and Metabiography. German Life and Letters 74, 416–438, https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/epdf/10.1111/glal.12309.

Schumacher, H. A. (1986): Caldas: un forjador de la cultura. Bogotá: Ecopetrol.

Schwartzman, R. (1996): Postmodernism and the practice of debate. Contemporary Argumentation and Debate 17, 1–18, https://www.uvm.edu/~debate/NFL/rostrumlib/SchwartzmanMar%2700.pdf.

Thurner, M. (2019): La invención de Humboldt. FLACSO Ecuador, Video MP4, 00:44:15, https://repositorio.flacsoandes.edu.ec/handle/10469/17649.

Thurner, M. (2023): Huellas sobre huellas sobre huellas. Procesos. Revista Ecuatoriana de Historia 58, 169–174, https://revistas.uasb.edu.ec/index.php/procesos/article/view/4593/4396.

Thurner, M. & J. Cañizares-Esguerra (eds.) (2023): The invention of Humboldt. On the geopolitics of knowledge. New York and London: Routledge.

Humboldt, A. & C. Kunth (1826): Französische Ankündigung der “Géographie des plantes, rédigée d’après la comparaison des phénomènes que présente la végétation dans les deux continens”, hg. v. Ulrich Päßler. In: Edition Humboldt Digital, hg. v. Ottmar Ette. Berlin-Brandenburgische Akademie der Wissenschaften, Berlin. Version 9, 04–07–2023, https://edition-humboldt.de/v9/H0016426.

Vila, P. ([1960] 2018): Caldas y los orígenes eurocriollos de la geobotánica. Revista de la Academia Colombiana de Ciencias Exactas, Físicas y Naturales 11 (42): xvii, https://raccefyn.co/index.php/raccefyn/article/view/753/474.

Wulf, A. (2015): The invention of Nature. Alexander von Humboldt’s New World. New York: Alfred A. Knopf.

“¡Ah! día 3 de abril de 802, ¿te borrarás alguna vez de mi memoria? Este día, día glorioso y terrible, hará época en mi vida. A las dos de la tarde se aparece en mi casa un criado del Barón de Humboldt, me entrega un pliego, conozco la letra del ilustre Mutis, mi corazón se conmueve, abro, veo este nombre: J. C. Mutis, mis lágrimas asoman, no puedo contenerme, beso esta firma respetable, leo ¡cielo santo! solo tú eres testigo de lo que pasó en mi alma; mis ojos se anegan; mi garganta se anuda; corro como loco; no hallo a un amigo a quién dar parte de mi felicidad y con quién disipar una parte del fuego que me abrasa; voy a casa de Humboldt, no le hallo; vuelvo a la mía; no atino, no puedo fijarme en nada; todo es amar a Mutis, todo es admirar su generosidad. ¡Qué cúmulo de ideas se me presentan! ¡Qué gloriosos trabajos los que voy a emprender! He aquí al mortal más feliz. Vuelvo a la casa del Barón; le hallo; pregunto por el sabio Mutis, por sus cartas. Me contesta este viajero con frialdad; me suprime el asunto principal; me lo niega directamente. En los primeros momentos de mi sorpresa creo al prusiano. ¡Qué asombro el mío! Veo de letra del ilustre Mutis estas cláusulas, que quedarán eternamente grabadas en mi corazón: Se cumplirán los ardientísimos deseos de usted si mi amadísimo el señor Barón de Humboldt nos franquea su consentimiento; tengo en mis manos un cuantioso libramiento. Oigo de boca de este sabio joven: no me dice nada el señor Mutis, no me ha escrito sobre el viaje de usted. ¡Qué distracción tan espantosa la de mi ilustre protector, decía dentro de mí! No puede ser: vuelvo a reconvenir y a preguntar, reconvengo con mi carta, con el libramiento. La fuerza de la verdad le oprime y me dice: Mi amigo, yo he mentido a usted: el señor Mutis me habla a la larga del asunto, pero yo, que he resuelto viajar solo, no quería dar a usted esta pesadumbre.”53

[Ah!, April 3rd 802, will you ever be erased from my memory? This day, a glorious and terrible day, will make an epoch in my life. At two o’clock in the afternoon, a servant of Baron de Humboldt appears at my house, he hands me a sheet of paper, I know the handwriting of the illustrious Mutis, my heart is moved, I open it, I see this name: J. C. Mutis, my tears appear, I cannot contain myself, I kiss this respectable signature, I read, holy heavens! You alone are witness to what has happened in my soul; my eyes water; my throat ties itself in knots; I run like mad; I cannot find a friend to whom to give part of my happiness and with whom to dissipate part of the fire that burns me; I go to Humboldt’s house, I cannot find him; I return to my own; I cannot see, I cannot fix on anything; everything is to love Mutis, everything is to admire his generosity. What an accumulation of ideas I am presented with! What glorious works I am going to undertake! Here is the happiest of mortals. I return to the Baron’s house; I find him; I ask for the wise Mutis, for his letters. This traveller answers me coldly; he suppresses the main subject; he denies it to me directly. In the first moments of my surprise, I believe the Prussian; how astonished I am! I see in the handwriting of the illustrious Mutis these clauses, which will remain eternally engraved in my heart: Your most ardent wishes will be fulfilled if my beloved Baron de Humboldt gives us his consent; I have in my hands a large sum of money. I hear from the mouth of this wise young man: Mr. Mutis tells me nothing, he has not written to me about your journey. What a dreadful distraction from my illustrious protector, I said to myself! It cannot be: I go back to remonstrate and to ask, I remonstrate with my letter, with the money Mutis sent. The force of truth oppresses him and says to me: My friend, I have lied to you: Mr. Mutis speaks to me at length about the matter, but I, who have resolved to travel alone, did not want to give you this grief.]

“No quise perder la brillante ocasión de comparar mis miserables instrumentos con los del señor barón de Humboldt, y hacer lo mismo con las observaciones verificadas en los lugares que nos eran comunes. Solo en Popayán habíamos observado ambos el calor del agua. Este ilustre viajero había hallado que el agua llovediza había hecho subir el licor del termómetro en esta ciudad a 203,3° de Farenheit, cuando el agua destilada me daba 202,21°, es decir, casi un grado menos. Me sorprendí al ver tan enorme diferencia, pues el agua de lluvia no puede producir un grado de más en el termómetro. ¿Estará el error, me decía, en nuestros instrumentos? Si lo hay, seguramente recae sobre mi termómetro. Deseando salir de la duda, suplico al señor barón me confíe el mismo termómetro que le había servido en Popayán para su observación: me concede traerlo a mi casa, lo pongo al lado del mío, dejo que adquieran la temperatura de mi aposento, y hallo que el del señor barón está justamente un grado más alto que el mío. ¿Pero cuál de los dos está fuera de la temperatura verdadera? El hielo es el mejor camino que se me presenta para salir de mi incertidumbre. Sumerjo ambos termómetros en él, y veo con admiración que el bello termómetro de Nairne se detiene en un grado sobre la congelación, y a 33 de Farenheit, cuando el mío bajaba con la mayor esactitud a 0 [grados] de Réaumur, y 32 Farenheit. Por consiguiente, es necesario quitar 1 grado de los resultados de las observaciones hechas con este instrumento.”54

[I did not want to miss the brilliant opportunity to compare my miserable instruments with those of Baron Humboldt, and to do the same with the observations made in the places we had in common. Only in Popayan had we both observed the heat of the water. This illustrious traveller had found that the rainy water had raised the liquor of the thermometer in this city to 203.3° Farenheit, when the distilled water gave me 202.21°, that is to say almost one degree less. I was surprised to see such an enormous difference, for rainwater cannot produce one degree too much in the thermometer. Is the error, I said to myself, in our instruments? If there is, surely it is in my thermometer. Wishing to get out of the doubt, I begged the baron to entrust me with the same thermometer that had served him in Popayan for his observation: he allowed me to bring it to my house, I put it beside mine, let them take the temperature of my room, and found that the baron’s was just one degree higher than mine. But which of the two was out of the true temperature? Ice is the best way out of my uncertainty. I dip both thermometers in it and see with admiration that the beautiful thermometer of Nairne stops at one degree above freezing, and at 33° Fahrenheit, when mine came down with the greatest accuracy to 0 [degrees] of Réaumur, and 32° Fahrenheit. Therefore, it is necessary to remove 1 grade from the results of the observations made with this instrument.]

“He trabajado de un modo extraordinario para corregir y añadir la parte práctica de Linneo traducida por Paláu, según el Species plantarum de Willdenow, que trae Mr. Bonpland; y en el día tengo muy avanzada la pentandria que es hasta donde llega. He tomado de la Flora del Perú los géneros: he visto una parte del herbario de Bonpland: he apuntado cuanto me ha parecido conveniente, y espero verlo todo, si no me reserva algo, como lo temo. ¿Quién sabe si el temor de que yo le arrebate algún género, alguna especie nueva, ha influido en la negativa del Barón?”55

[I have worked in an extraordinary way to correct and add the practical part of Linnaeus translated by Palau, according to the Species plantarum of Willdenow, which Mr. Bonpland brings; and to-day I have very advanced the pentandria which is as far as it goes. I have taken from the Flora of Peru the genera: I have seen a part of Bonpland’s herbarium: I have noted down what I have found convenient, and I hope to see it all, if he does not reserve something for me, as I fear. Who knows whether the fear that I may snatch from him some genus, some new species, has influenced the Baron’s refusal?]

“Una de las cosas que he notado en los trabajos geográficos de este sabio es que mezcla lo cierto con lo dudoso; que, deseoso de abrazarlo todo, diseña al lado de un retazo digno de D’Anville, otro por simples relaciones de gentes ignorantes. No soy el Zoilo de este grande hombre, detesto el vicio de deprimir los trabajos ajenos, pero es preciso decir la verdad, y creo que los geógrafos posteriores tendrán que corregir bastante, no en los lugares que haya examinado este viajero célebre, sino en los que estén levantados por puras relaciones.”56

[One of the things I have noticed in the geographical works of this wise man is that he mixes the certain with the doubtful; that, wishing to embrace everything, he designs beside a piece worthy of D’Anville another by simple relations of ignorant people. I am not the Zoilus of this great man, I detest the vice of depressing the works of others, but the truth must be told, and I believe that later geographers will have to correct a lot, not in the places that this famous traveller has examined, but in those that are raised by pure relationships.]

“Mi alegría con lo que usted me dice de Humboldt y de Bonpland puede haber igualado a la suya; yo suscribo gustoso a todo lo que usted dice de estos viajeros. Nosotros, que conocemos el carácter de la nación que jamás ha dejado de acompañar sabios españoles en todas las expediciones que se han hecho en sus dominios, ¿no debemos extrañar que no acompañen a los prusianos un botánico, un mineralogista y un astrónomo de casa? Si no es así, lo siento en mi corazón, porque ¿qué gloria no resultó a la nación de la asociación de los dos Oficiales españoles en el viaje al Ecuador? Ya sabe usted que Ulloa y Juan no podían, cuando vinieron a América, ponerse al lado de Godin, de Bouguer y de La Condamine; pero volvieron a Europa dignos de ocupar un lugar en la Academia de las Ciencias. Usted me lisonjea cuando se imagina que podría acompañar a estos sabios y hacer el papel de Ulloa para con éstos: no me hallo capaz de desempeñar la confianza de la nación en caso [de] que se efectuase; pero juzgando por mis sentimientos, ¡qué placer, qué gloria para mí verme al lado de un astrónomo, de un botánico, de un minero ilustrado!”57

[My joy at what you tell me of Humboldt and Bonpland may have equalled yours; I gladly subscribe to all that you say of these travellers. We, who know the character of the nation that has never failed to accompany Spanish scholars in all the expeditions that have been made in its dominions, should we not be surprised that the Prussians are not accompanied by a botanist, a mineralogist and an astronomer from home? If not, I am sorry in my heart, for what glory did not result to the nation from the association of the two Spanish Officers on the voyage to Ecuador? You know that Ulloa and Juan could not, when they came to America, stand beside Godin, Bouguer and La Condamine; but they returned to Europe worthy of a place in the Academy of Sciences. You flatter me when you imagine that I could accompany these learned men and play Ulloa’s part for them: I do not find myself capable of fulfilling the confidence of the nation in the event of it taking place; but judging by my feelings, what a pleasure, what a glory for me to see myself at the side of an astronomer, of a botanist, of an enlightened miner!]

1 Thurner, M. & J. Cañizares-Esguerra (2023).

2 Wulf, A. (2015).

3 Thurner, M. & J. Cañizares-Esguerra (2023, xv).

4 Renner, S. S., U. Päßler, U. and P. Moret (2023). For a complementary critique on Humboldt’s Tableau Physique, see Moret, P. et. al. (2019). For a recent elaboration on Humboldt’s Naturgemālde, see Knobloch, E. (2023).

5 Gómez Gutiérrez, A. (2021; 2023a, 76–115; 2023b, 175; 2024a).

6 For previous assessments of the Humboldt-Caldas simultaneity on Biogeography, see Gómez Gutiérrez, A. (2016; 2024b).

7 Jackson, S. T. (2009, 13–14).

8 Gómez Gutiérrez, A. (2023a, 82–83).

9 Vila, P. ([1960] 2018, xvii).

10 Gómez Gutiérrez, A. (2016).

11 Rupke, N. A. (2005).

12 Rupke, N. A. (2021, 416).

13 Kutzinski, V. (2010, 102). For a personal elaboration on an eventual avatar in the context of Humboldt-Caldas relationships, see Gómez Gutiérrez, A. & J. G. Portilla (2021).

14 For the prominent characteristics of postmodernism, see Schwartzman, R. (1996, 1).

15 Thurner, M. (2019).

16 Rebok, S. (2019, 2024a, 2024b).

17 Rebok, S. (2024b, 232).

18 Daum refers the transition from exceptionalism to heroization in Humboldt’s case and warns scholars against dismissing “this new exceptionalism because of its simplifications and popular appeal beyond academic discussions”. However, he states, “we are well advised to take it seriously and register what it says about readers’ receptiveness to heroic narratives” (Daum, 2024, 14).

19 Puig-Samper, M. A. (2023).

20 Ibidem, 148: My own translation, as the original review was published in English.

21 Evidence of Humboldt’s need to acknowledge Mutis can be deduced from his explicit recommendation to Bonpland in a letter written in Berlin in 1806, while preparing their two volumes on Plantes équinoxiales (not his Géographie des plantes): “De grâce, faites graver le vieux Mutis, qu’il ne meurt pas avant que nous l’ayons fait. Nous lui avons coûté tant. Mais que cela soit peu coûteux” (Hossard, 2004, 39) [original underlining, italics added]. Mutis died in 1808, the year in which his portrait was published in the first volume of Plantae Aequinoctiales, unaware of this late recognition.

22 Ibidem.

23 In Spanish: “aportaciones paralelas”.

24 Gómez Gutiérrez, A. (2023a, 76).

25 This original document has lost its final folio/a, as kept in Berlin’s Staatsbibliothek (Caldas, F. J., 1802).

26 As Ulrich Päßler’s work has shown, this fact does not imply that Humboldt had not reflected on the occurrence of plants on certain heights before late 1802, or even before meeting Caldas. The journal entries about the path up from Honda to Bogotá contain many observations on the occurrence of specific plants on specific heights. These observations were continued on the path from Popayán to Quito (Päßler, 2024, 95–99). It should be pointed out, however, that the later path was followed in the company of Caldas after their first personal encounter near Ibarra.

27 For a development of the succession of geographical and biogeographical profiles in Humboldt and Caldas, see Gómez Gutiérrez, A. (2023, 100–107).

28 Mutis, in Caldas, F. J. ([1802] 1917a, 148).

29 Ibidem, added italics.

30 Vila, P. ([1960] 2018, xvii).

31 Humboldt, A. & Kunth, C. (1826, 1–2): communicated by Ulrich Päßler.

32 Caldas, F. J. (1808, 8): [La región media de los Andes (desde 800 hasta 1.500 toesas), con un clima dulce y moderado (de 10° a 19° Réaumur), produce árboles de alguna elevación, legumbres, hortalizas saludables, mieses, todos los dones de Ceres; hombres robustos, mujeres hermosas de bellos colores, son el patrimonio de este suelo feliz. Lejos del veneno mortal de las serpientes, libres del molesto aguijón de los insectos, pasean sus moradores los campos y las selvas con entera libertad. El buey, la cabra, la oveja, les ofrecen sus despojos y les acompañan en sus fatigas. El ciervo, la danta (Tapirus L.), el oso, el conejo, etc., pueblan los lugares a donde no ha llegado el imperio del hombre. La parte superior (desde 1.500 hasta 2.300 toesas), bajo un cielo nebuloso y frío, no produce sino matas, pequeños arbustos y gramíneas. Los musgos, las algas y demás criptógamos ponen término a toda la vegetación a 2.280 toesas sobre el mar. Los seres vivientes huyen de estos climas rigurosos, y muy pocos se atreven a escalar estas montañas espantosas. De este nivel hacia arriba ya no descubren sino arenas estériles, rocas desnudas, hielos eternos, soledad y nieblas].

33 Humboldt, A. (1809).

34 Caldas, F. J. (1809, 121–163).

35 Humboldt, A. (1805–1807, 115).

36 Amaya, J. A. (2023, 116–147).

37 Ibidem, 134.

38 Mutis, J. C. (1954–2024).

39 Ibidem, 135.

40 Amat-García, G. & Agudelo-Zamora, H. D. (2020, 201–202).

41 Caldas, F. J. ([1802] 1917a, 147–148): original italics.

42 Caldas, F. J. ([1802] 1917b, 154): added italics.

43 Caldas, F. J., quoted in Schumacher (1986, 10–11). For a detailed analysis of Humboldt’s influence in the construction of the first American Observatory still standing, see Gómez Gutiérrez, A. (2024a).

44 Humboldt A., et al. (1834, 24). For a thorough analysis of this contribution of Caldas to Humboldt’s cartography, see Mejía Macía, S. A. (2022).

45 This first sentence was written in French “Demandez a Mr. Caldas afin qu’il procure de S. Fe les notions suivantes”, and the subsequent five geographical questions were written in Spanish.

46 https://digital.staatsbibliothek-berlin.de/werkansicht?PPN=PPN78798096X&PHYSID=PHYS_0001&view=overview-info.

47 For a detailed relation of Humboldt’s encounters in his American Expedition, particularly in the New Kingdom of Granada, see Gómez Gutiérrez, A. (2018).

48 Caldas, F. J. ([1801] 1917, 49–50). For the complete paragraph in this letter see Note 5.

49 Caldas, F. J. ([1802] 2016a, 389).

50 Päßler, U. Personal communication.

51 For a for a thorough description and differentiation of these two concepts see Daum, A. W. (2024), where he suggests that Humboldt himself was less “Humboldtian” than this heuristic concept suggests.

52 Primary sources are transcribed in Spanish, as produces by Caldas, and translated to English by the author in square brackets.

53 Caldas, F. J. ([1802] 1917a, 147–148): original italics, bolds added.

54 Caldas, F. J. ([1802] 2016b, 93–94).

55 Caldas, F. J. ([1802] 1966, 294).

56 Caldas, F. J. ([1802] 1849, 553–554).

57 Caldas, F. J. ([1801] 1917, 49–50).