Reinhard Andress

In a previously published article in HIN under the title of “Eduard Dorsch and his unpublished poem on the occasion of Humboldt’s 100th birthday,” I elaborated on Dorsch’s poem that was read in Detroit in front of a German-American audience on Sept. 14, 1869, a day widely celebrated in the US in honor of Humboldt. Although it was not surprising that Dorsch wrote the occasional poem in the first place given his affinities with Humboldt’s world of thought, a discovery of a second occasional poem upon further research in Dorsch’s voluminous papers was indeed unexpected, in this case read on the same date in Monroe, Michigan. Although there are a number of similarities between the Detroit and Monroe versions, there are enough differences that warrant this addendum to my original article.

In einem bereits in HIN veröffentlichten Artikel mit dem Titel Eduard Dorsch und sein unveröffentlichtes Gelegenheitsgedicht zu Humboldts 100. Geburtstag ging ich auf Dorschs Gedicht ein, das am 14. September 1869 vor einem deutsch-amerikanischen Publikum in Detroit verlesen wurde, an einem Tag, der überall zu Ehren Humboldts in den USA gefeiert wurde. Obwohl es nicht überraschend ist, dass Dorsch angesichts seiner Affinität zu Humboldts Gedankenwelt das Gedicht überhaupt schrieb, war der Fund eines zweiten Gelegenheitsgedichts in Dorschs umfangreichem Nachlass dennoch unerwartet, in diesem Falle am selben Tag in Monroe, Michigan verlesen. Obwohl es eine Reihe von Ähnlichkeiten zwischen den Detroit- und Monroe-Versionen gibt, tauchen auch genug Unterschiede auf, um diesen Nachtrag zu meinem ursprünglichen Artikel zu rechtfertigen.

En un artículo ya publicado en HIN bajo el título de “Eduard Dorsch y su poema inédito con motivo del centenario de Humboldt”, abordé el poema de Dorsch leído en Detroit frente a una audiencia germano-estadounidense el 14 de septiembre de 1869, un día ampliamente celebrado en los Estados Unidos en honor a Humboldt. Aunque no sorprende que Dorsch escribiera el poema de ocasión debido a sus afinidades con la cosmovisión de Humboldt, lo inesperado fue el hallazgo de un segundo poema para la misma ocasión durante un estudio adicional de los voluminosos papeles de Dorsch. Este segundo poema fue leído en la misma fecha en Monroe, Michigan. Si bien existe una serie de similitudes entre las versiones creadas para Detroit y Monroe, también hay suficientes diferencias que justifican este apéndice a mi artículo original.

In a previously published article in HIN under the title of “Eduard Dorsch and his unpublished poem on the occasion of Humboldt’s 100th birthday” (cf. Andress 2018), I elaborated on Dorsch’s emigration from Germany to the US in 1849 as one of the 48ers, ultimately settling in Monroe, Michigan. There, he successfully practiced his medical profession with additional wide-ranging interests in the natural sciences and humanities as befitted an individual educated in the spirit of the “Bildungsbürgertum”. The poem was read by a certain L. Jensen in Detroit, some 47 miles north of Monroe, in front of a German-American audience on Sept. 14, 1869, a day widely celebrated in the US in honor of Humboldt.

Although it was not surprising that Dorsch wrote the occasional poem in the first place given his affinities with Humboldt’s world of thought, as I also explain in the article, it was indeed unexpected when I came across a second occasional poem for Humboldt’s same birthday upon further research in Dorsch’s voluminous papers, in this case read on the same date in Monroe. Although there are a number of similarities between the Detroit and Monroe versions, there are enough differences that warrant this addendum to my original article. Let me first quote the poem in full length here with some notes before making comparisons between the two versions and drawing some further contextual conclusions.

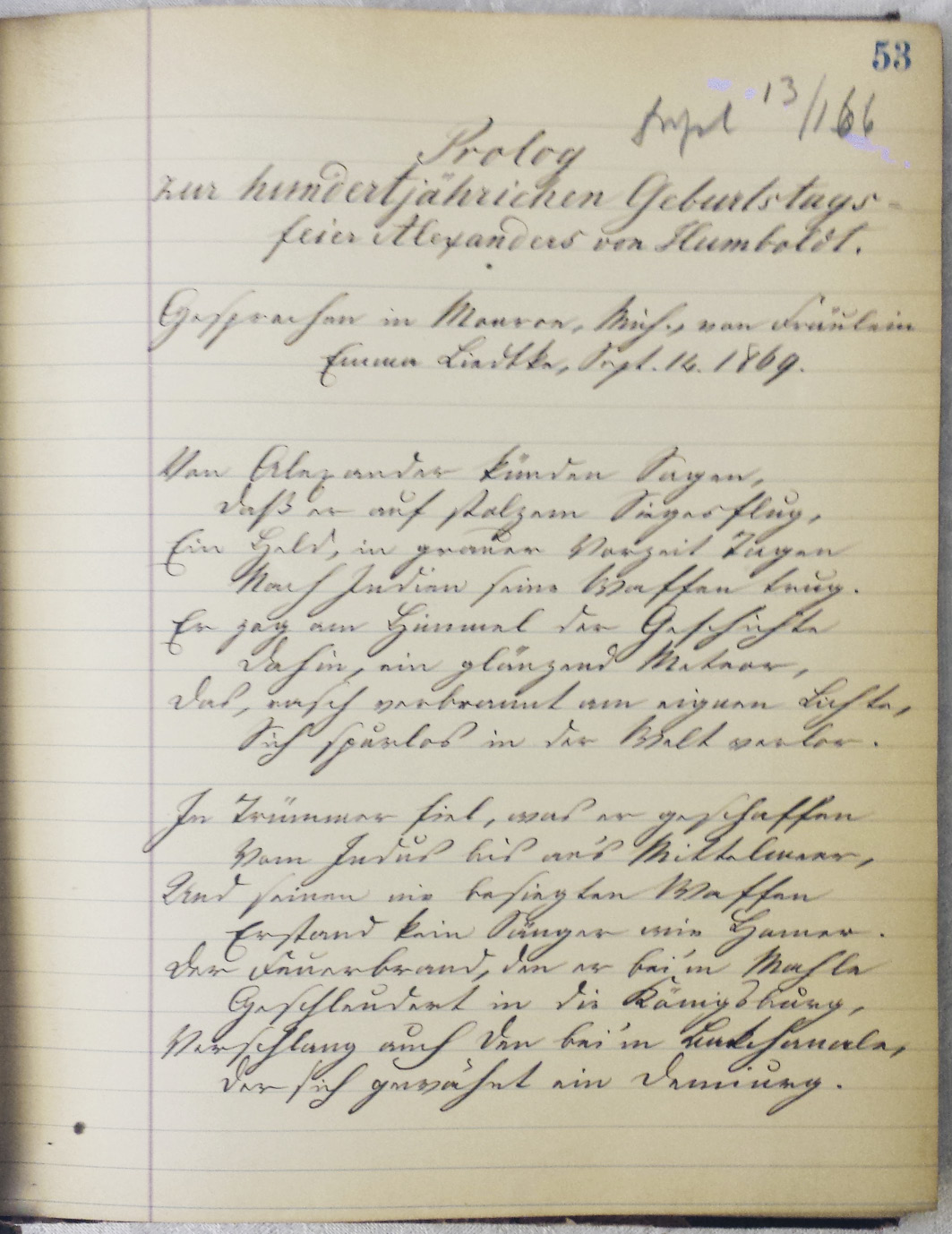

Prolog

zur hundertjährichen Geburtstagsfeier Alexanders von Humboldt.

Gesprochen in Monroe, Mich., von Fräulein Emma Liedtke, Sept. 14. 1869

Von Alexander künden Sagen,

Daß er auf stolzem Siegerflug,

Ein Held, in grauer Vorzeit Tagen

Nach Indien seine Waffen trug.

Er zog am Himmel der Geschichte

Dahin, ein glänzend Meteor,

Das, rasch verbrannt am eignen Lichte,

Sich spurlos in der Welt verlor.

In Trümmer sind, was er geschaffen

Vom Indus1 bis an’s Mittelmeer,

Und seinen nie besiegten Waffen

Erstand kein Sänger wie Homer.

Der Feuerbrand, den er bei’m Mahle

Geschleudert in die Königsburg,

Verschlang auch den bei’m Bakchanale,

Der sich gewähnet ein Demiurg.

Abb. 1: Dorsch’s Unpublished Poem, p. 53. Source: Dorsch Memorial Library.

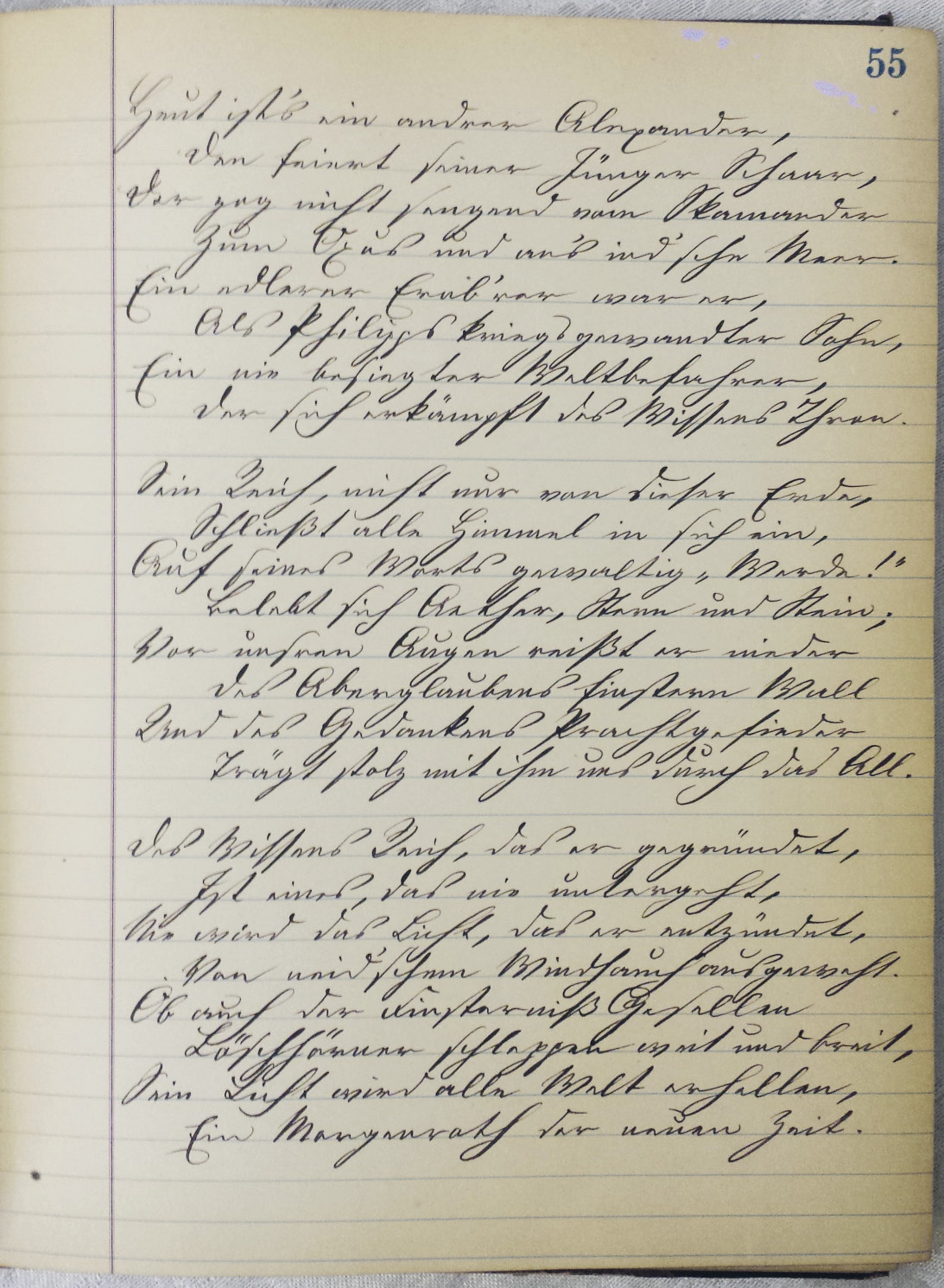

Heut ist’s ein andrer Alexander,

Den feiert seiner Jünger Schaar,

Der zog nicht sengend von Skanander2

Zum Oxus3 und an’s ind’sche Meer.

Ein edlerer Erob’rer war er,

Als Philipps4 kriegsgewandter Sohn,

Ein nie besiegter Weltbefahrer,

Der sich erkämpft des Wissens Thron.

Sein Reich, nicht nur von dieser Erde,

Schließt alle Himmel in sich ein,

Auf seines Worts gewaltig „Werde!“

Belebt sich Aether, Stern und Stein;

Vor unsren Augen reißt er nieder

Des Aberglaubens finstern Mull

Und des Gedankens Prachtgefieder

Trägt stolz mit ihm uns durch das All.

Des Wissens Reich, das er gegründet,

Ist eines, das nie untergeht,

Nie wird das Licht, das er entzündet,

Von neid’schem Windhauch ausgeweht.

Ob auch der Finsterniß Gesellen

Löschhörner schleppen weit und breit,

Sein Licht wird alle Welt erhellen,

Ein Morgenroth der neuen Zeit.

Abb. 2: Dorsch’s Unpublished Poem, p. 55. Source: Dorsch Memorial Library.

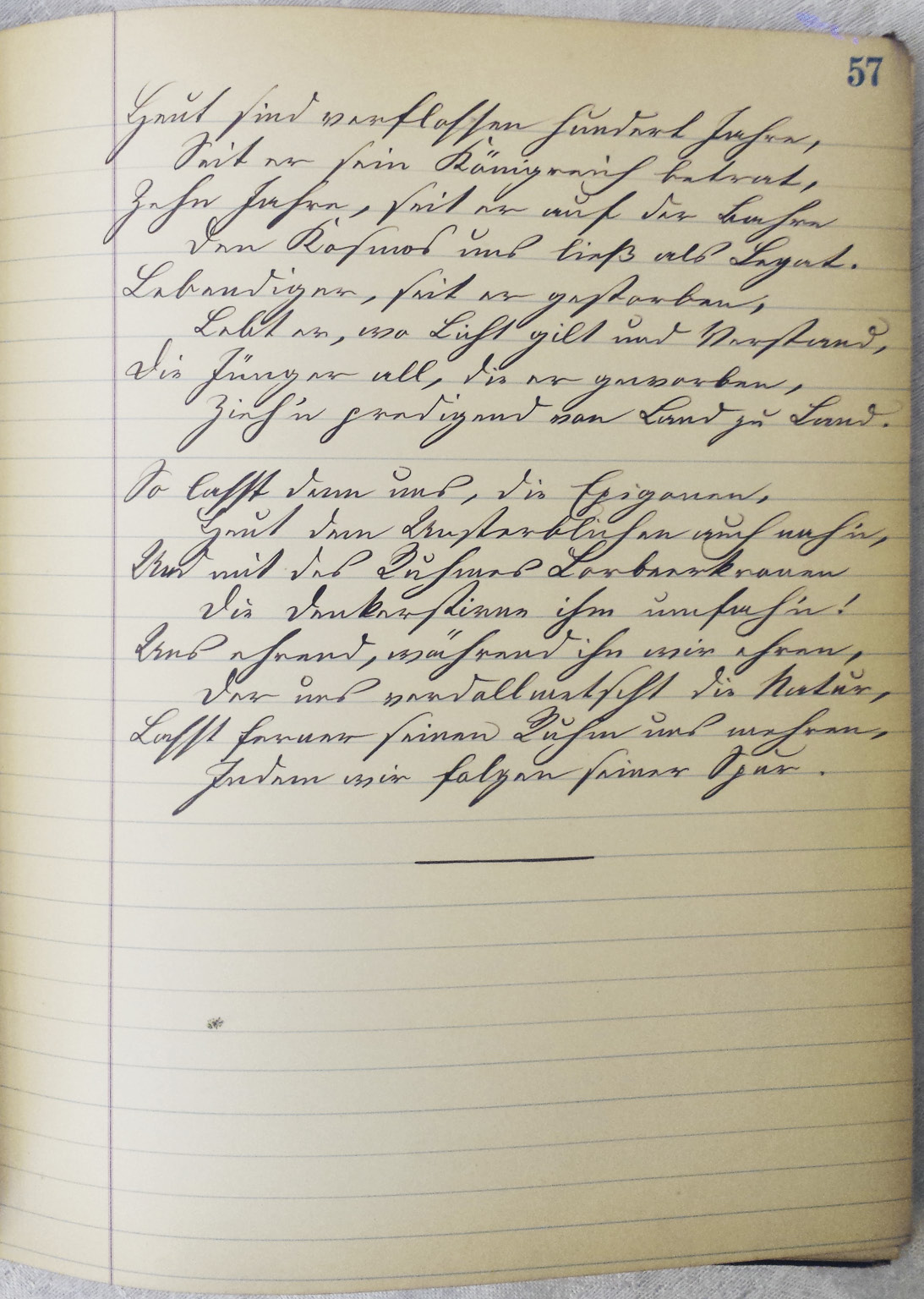

Heut sind verflossen hundert Jahre

Seit er sein Königreich betrat,

Zehn Jahre seit er auf der Bahre

Den Kosmos uns ließ als Legat.

Lebendiger, seit er gestorben,

Lebt er, wo Licht gilt und Verstand,

Die Jünger all, die er geworben,

Zieh’n predigend von Land zu Land.

So lasst denn uns, die Epigonen,

Heut dem Unsterblichen auch nah’n,

Und mit des Ruhmes Lorbeerkronen

Die Denkerstirne ihm umfachen!5

Uns ehrend, während ihn wir ehren,

Der uns verdollmetscht die Natur,

Lasst ferner seinen Ruhm uns mehren,

Indem wir folgen seiner Spur.

Abb. 3: Dorsch’s Unpublished Poem, p. 57. Source: Dorsch Memorial Library.

On the formal level, the Detroit version is longer with nine stanzas of eight lines each that take on enclosed ABBA and alternate CDCD rhyme schemes within each stanza, whereas the Monroe version contains only seven eight-line stanzas with a more straight-forward, double alternate rhyme scheme of ABAB CDCD. Although both versions tell the listeners there are many reasons to celebrate Humboldt in the entire world for his contributions to science, the greater length and sophistication of rhyme scheme in the Detroit version point to a more complex content as well. For example, the poem takes time to imbed Humboldt in his South American trip, which is only implicitly present in the Monroe version, specifically citing the Antisana and Chimborazo mountain climbs as metaphors on the way to proclaiming the equally new heights that Humboldt achieved in science as well. Along the way, Dorsch makes historical and mythological references to Ancient Greece by bringing Aristotle, Alexander the Great, Empedocles and Pan into the text, also citing the Manes of the ancient Roman religion. He ultimately lends Humboldt a quasi-divine status as the “Hohenpriester der Natur” or “[d]es Lichts Apostel” (Andress 2018), dedicated to seeking out the interwoven cause and effect of the higher truth of nature, “[d]as ewige Naturgesetz” (Andress 2018), something the church would prefer to keep under wraps. As I point out in my original article, Dorsch’s own very clear anti-clerical stance (“Des Glaubens morschen Stab verschmähend” [Andress 2018]) no doubt drives a significant part of the poem that ultimately urges the listeners to follow Humboldt’s footsteps in pursuit of knowledge toward an enlightened future.

What is a passing positive reference to Alexander the Great in the Detroit version (“Ein Held war er, ein Alexander / Der siegreich seine Waffen trug” [Andress 2018]) becomes the point of departure for the Monroe version that takes two of its seven stanzas to trace the image of a destructive and ephemeral conqueror before transitioning in the third stanza to the other Alexander, setting up a contrast with the permanence of the world of knowledge Humboldt has conquered in a very different, peaceful way. The poem then goes on to characterize Humboldt less in the divine terms of the Detroit version, nonetheless still celebrating the knowledge that Humboldt shared with us about the earth and heavens, in the process dissipating superstitions. In that regard, the church is implied more as a factor of resistance as opposed to the more explicit anti-clerical stance of the Detroit version. Although both poems urge the listeners to become avid followers of Humboldt, the Monroe version does all of this more rapidly and with less imagery, mentioning Cosmos as the repository for all of Humboldt’s knowledge of nature that he has “translated” for us.

Once Dorsch has moved beyond Alexander the Great in the Monroe version, it is really only four stanzas that are fully dedicated to celebrating Humboldt as opposed to nearly all nine of the Detroit version. One cannot help but think that Dorsch got somewhat lost in or carried away with his ruminations about Alexander the Great. His interpretation of the conqueror is also shortsighted since the conquerer’s more permanent legacy can be seen, for example, in expanding the trade routes between East and West or founding cities that continue today as significant cultural centers. Dorsch’s desire to set up a contrast between the two Alexanders obscure the ancient Greek’s accomplishments, as brutal as his wars no doubt were. The tone and quality of the Detroit version might ultimately strike us as being overly histrionic from today’s perspective, but within the context of the solemn celebration of Humboldt’s 100th birthday roughly 150 years ago, it is the better occasional poem.

Audience may have also played a role regarding the Monroe version’s more simple form and less sophisticated content. According the U.S. Bureau of Census, Detroit, already founded in 1701, had a population of nearly 80,000 in 1870 and at the time was the 18th largest city in the US (cf. “Population”). It was a center of US industrial development in the 19th century and had become quite urban. In contrast, the population of all of rural Monroe County numbered just over 5,000, including Monroe itself, not founded until 1827, with just a few hundred inhabitants (cf. “Bureau”). The town, named after President James Monroe (1758–1831), was a sleepy provincial place and has remained such. As regards German immigrants, there was a substantial number of them in Michigan and their contributions were many to all walks of life such as agriculture, the sciences, arts, medicine, law, engineering, architecture, journalism, business and industry (cf. Russell 1927). Many of them settled in Detroit and were, in fact, so numerous there that a part of the city, Germantown, was named after them with countless German-American organizations attending to their social and cultural needs, such as the Harmonie Club or the Concordia Society, to name just two. Although there were German immigrants in Monroe as well, their presence was simply more modest in numbers and most likely in background as well since the more educated no doubt gravitated toward an urban area like Detroit.

To some extent this general situation may explain some of the differences between the two poems. In Detroit there was more potential of an urban middle class of German-Americans who understood and appreciated the more formal qualities and references of the Humboldt poem Dorsch wrote for them. In Monroe, he may have assumed his audience could still handle a reference to a historical figure like Alexander the Great and left it at that. In addition, the more rural and religious nature of smaller American communities like Monroe may explain why Dorsch elected to tone down his anti-clerical stance of the Detroit version.

Although I was not able to establish exactly where the Detroit version was read, it is clear for the Monroe version. On Sept. 9, 1869 we read the following in The Monroe Commercial, the weekly, four-page newspaper of Dorsch’s hometown:

Wednesday next, the 15th inst. [abbreviation for “instant”, an older term for the current month], is the 100th anniversary of the birth of Alexander von Humboldt.—The Germans of this city will celebrate the ocbasion [sic!] in a becoming manner. All the German civic associations will turn out, and after a parade through the streets with music, will repair to Noble’s grove, where appropriate addresses will be made, and a pic-nic will be held. The procession will form at Court House square, at 1 o’clock P.M. (“Humboldt Fest” 1869: 3)

Although the newspaper initially got the date wrong since the event took place on Sept. 14, it was a major event for a small town like Monroe. A report in The Monroe Commercial a week later gives us some details:

The celebration of the 100th anniversary of the birth of Humboldt, on Tuesday, passed off very successfully. The procession formed at the public square a one o’clock, as follows: Monroe Cornet Band, Germania Fire Co., No. 1, President, Vice Presidents, and Common Council, Monroe Maenerchor [sic!], Monroe Silver Band, Concordia, Tuetonia, Workingsmen’s Aid Society, &c. The procession marched through the principal streets and to Noble’s grove, where several addresses were listened to, interspersed with music and singing. Ex-Mayor Waldorf acted as President of the day. A prologue was read by Miss Emma Liedtke, an address suitable to the occasion was delivered by N. Rupp, Esq., and short addresses were also made by E.G. Morton, Mayor Sawyer and A. Gierschke, and the two bands and the Maenerchor [sic!] filled up the time with pleasing music. (“The Humboldt Fest” 1869: 3).

The fact that the “prologue” was read by the same Emma Liedtke mentioned at the outset of Dorsch’s Monroe version of the occasional poem, also titled “Prolog,” confirms in all likelihood that it was indeed his poem that kicked off the formal festivities to honor Humboldt. Dorsch was no doubt in attendance. The presence of the Workingmen’s Aid Society, originally organized in 1865 (cf. Wing 1890: 342), points to the more modestly educated audience I outlined above.

What ultimately becomes clear here is that the grand celebrations in the US on the occasion of Humboldt’s 100th birthday were not just a matter of the large urban areas like Detroit. So appreciated and revered was Humboldt in the North America of the 19th century that those celebrations even found their way into the more rural counties and such small towns like Monroe.

Andress, Reinhard: Eduard Dorsch and his unpublished poem on the occasion of Humboldt’s 100th birthday. HiN – Alexander von Humboldt im Netz. Internationale Zeitschrift für Humboldt-Studien, [S.l.], v. 19, n. 36, p. 17–34, may 2018. ISSN 1617-5239. Verfügbar unter: http://www.hin-online.de/index.php/hin/article/view/261. DOI:http://dx.doi.org/10.18443/261 (accessed Sept. 23, 2019).

Bureau of Census figures for Monroe. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Monroe,_Michigan (accessed Sept. 23, 2019).

“Humboldt Fest” (1869). The Monroe Commercial, Vol. 29, Nr. 42 (Sept. 9, 1869), p. 3.

“The Humboldt Fest” (1869). The Monroe Commercial, Vol. 29, Nr. 43 (Sept. 16, 1869), p. 3.

“Population of the 100 Largest Urban Places: 1870,” U.S. Bureau of the Census. https://www.census.gov/population/www/documentation/twps0027/tab10.txt (accessed Sept. 23, 2019).

Russell, John Andrew (1927): The Germanic Influence in the Making of Michigan. Detroit: The University of Detroit, 1927.

Wing, Talcott E., ed. (1890): History of Monroe County Michigan. New York: Munsell & Company, 1890, p. 342.

1 A southward flowing river in Southern Asia, located above all in Pakistan.

2 The old name of a Turkish river, today the Karamenderes. According to Homer’s Ilias, the Trojan War was fought in the proximity of its lower end.

3 The historical and Latin name of a Central Asian river known today as the Amu Darya, which flows through Afghanistan, Tajikistan, Turkmenistan and Uzbekistan.

4 Philip II of Macedonia (359–336 BC), father of Alexander the Great.

5 A seldom, poetic word synonymous with the more common “umfächeln”.