Sandra Rebok, Timothy Winkle

While the lack of religion in Alexander von Humboldt’s work and the criticism he received is well known, his relationship with Freemasonry is relatively unexplored. Humboldt appears on some lists of “illustrious Masons,” and several lodges carry his name, but was he really a member? If so, when and where did he join a lodge? Are there any comments by him about Freemasonry? Who were the renowned Masons he was surrounded by? This paper examines these questions, but more importantly it analyzes what a membership might have meant for Humboldt’s scholarly work. It looks particularly at the unprecedented success he enjoyed in the United States in the early 19th century and the factors behind it. What could he have gained from these connections and how was he viewed by Masonic leaders and lodges in the trans-Atlantic world?

Mientras que la falta de religiosidad en la obra de Alexander von Humboldt, así como las críticas por ello recibidas, son bien conocidas, su posible relación con la masonería es relativamente incógnita. Humboldt aparece en algunas listas de “masones ilustres” y varias logias llevan su nombre pero, ¿fue realmente miembro de una de ellas? Y en este supuesto, ¿cuándo y dónde se adhirió?, ¿existen comentarios suyos sobre la masonería?, ¿qué masones de renombre le rodearon? Este artículo estudia estas cuestiones pero, de manera más importante, analiza lo que la membresía de una logia masónica podría haber significado para el trabajo académico de Humboldt. En particular, mira el éxito sin precedentes del que disfrutó en los Estados Unidos a comienzos del siglo xix y los motivos para ello. ¿Qué podria haber ganado de estas conexiones y cómo fue visto por los líderes y logias masónicas en el mundo transatlántico?

Während das Fehlen einer religiösen Haltung in Humboldts Werk, sowie die Kritik, die er diesbezüglich erhalten hat, allgemein bekannt sind, ist sein möglicher Bezug zur Freimaurerei noch weitgehend unerforscht. Zwar erscheint Humboldt auf einigen Listen von „illustren Freimaurern“, zudem tragen mehrere Logen seinen Namen, aber die Frage bleibt offen, ob Humboldt wirklich ein Freimaurer war. Wenn ja, wann und wo ist er einer Loge beigetreten? Gibt es vielleicht Kommentare von ihm zu dieser Art von Geheimbünden? Und wer waren die bekanntesten Freimaurer in seiner Umgebung? Der Artikel beantwortet diese Punkte, aber wichtiger noch geht er der Frage nach, was eine Mitgliedschaft für Humboldts wissenschaftliche Arbeit bedeutet haben könnte, insbesondere im Hinblick auf den herausragenden Erfolg, den er in den Vereinigten Staaten zu Beginn des 19. Jahrhunderts hatte und die Gründe hierfür. Was hätten solche Verbindungen für ihn bedeutet und wie wurde er von den wichtigsten freimaurerischen Persönlichkeiten und Logen in der transatlantischen Welt wahrgenommen?

On the occasion of the celebration of Alexander von Humboldt’s 250th anniversary, it is an appropriate moment to reconsider or re-examine certain attributions that have been ascribed to him over time, with more or less foundation. While the lack of religion in Humboldt’s work, both as fundament for his worldview and as motivation for his acting, has been the topic of several discussions, his potential relationship to the world of fraternalism and specifically to Freemasonry—something Gordon Wood and others have considered a secular equivalent or “surrogate religion for enlightened men”1—remains uncertain. Though this topic has raised some curiosity, and a potential Masonic connection has been occasionally questioned, it has not been treated in-depth. Masons have traditionally claimed Humboldt: His name appears on some lists of “illustrious Masons”, several lodges carry his name, and to a certain extent he seemed to embody Masonic ideals. However, this appropriation raises the doubt if he was really a member of this or any secret society? And in this case, when and where would he have joined a lodge? Was it still in Europe or during his extended travels through the New World (1799–1804)? Would a membership have been necessary or beneficial for him in order to carry out his scientific program? Could a closer affinity to the Masonic world possibly be an additional explanation for the success he enjoyed with his diverse projects during the 19th century? In the United States, in particular, where the ideals of the young republic intertwined with those of Freemasonry, what were the factors that made Humboldt a potent figure for Masons and non-Masons alike? If he was not a Freemason, what explains his adoption, or rather co-option, by the fraternity? What is it, beyond a general admiration for Humboldt, that Masonic leaders and lodges in the trans-Atlantic world saw in the Prussian explorer?

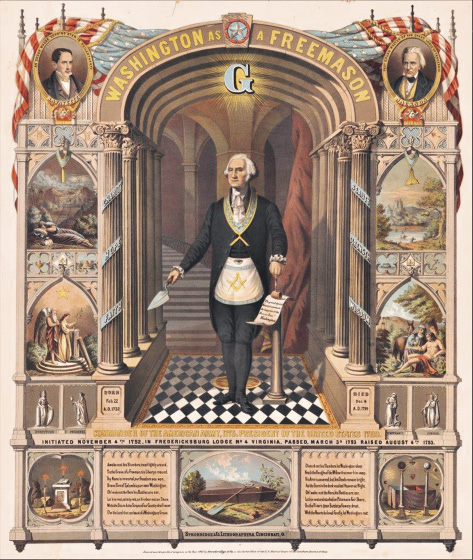

Freemasonry, an early product of the Age of Reason, played an important role in Enlightenment thinking. Masonic lodges, based on ritual and allegorical teaching rooted in both Old Testament accounts and allegorical symbolism drawn from medieval stonemasonry, originated in Great Britain in the 17th century. The first formal organization came with the establishment of the Grand Lodge of England in 1717, and the fraternity expanded steadily to other European nations, as well as North America, in the next several decades. With their direct links to Britain, the American colonies experienced steady growth in Freemasonry from the 1730s, with lodges operating in urban centers such as Boston and Philadelphia, and as far south as Savannah, Georgia, and steadily expanding throughout the colonies in the following decades.2 American Freemasons followed the example of their English brethren, using their membership as a means of earning social status and recognition through their association with an honorable and charitable tradition.3 While European Freemasonry spread, in part, as a counter to the regimentation of government, later supported by the ideals of the French Revolution, in America, Masonic principles were, at least, compatible with the aims of the new republic and, at most, influential in the establishment and identity of the burgeoning nation. As such, American Freemasonry would encounter little in the way of social, religious, or governmental reprisal. Masonic membership was often intertwined with membership in revolutionary bodies such as Boston’s Sons of Liberty, and some Masonic lodges were used as gathering places to network and coordinate resistance against unpopular British policies. Besides Benjamin Franklin, other prominent figures of the “Founding Generation” who belonged to the fraternity include Samuel Adams, John Hancock, Paul Revere, James Monroe, and, most famously, George Washington.4 It is of note, however, that while a number of early founders and leaders of the young republic were Freemasons, many of the leading personalities of the period did not join. In particular, those who developed the philosophies and intellectual infrastructure of the new nation—among them James Madison, Thomas Jefferson, John Adams, Thomas Paine, George Mason, Alexander Hamilton—were not Freemasons.

On both sides of the Atlantic, individual Freemasons also furthered the growth of Enlightenment learning and helped to lay some of the foundations of modern scientific inquiry, something certainly encouraged by the precepts of the fraternity. In addition, Freemasons were instrumental in founding several pre-eminent scientific institutions in the world. One such organization was the Royal Society in London, begun in 1660 with membership that included early Freemasons such as founder Sir Robert Moray, Elias Ashmole, and George Villiers, 2nd Duke of Buckingham.5 Cross-membership between the Royal Society and the fraternity was common in the 18th century6 and sometimes high profile—Society member James Anderson would write the first history of Freemasonry in 1723, and early Grand Master John Theophilus Desaguliers was also an influential proponent of Newtonian theory within the Royal Society.7 By the latter part of the century, Freemasonry provided another link between the Society’s scientists and the wealthy amateurs whose patronage was so essential. This period was overseen by Sir Joseph Banks, who served as president of the Royal Society from 1778 until his death in 1820. Banks, a Freemason himself, also had a key role as inspiration for the young Humboldt, during his visit to London, defining his vocation as naturalist and explorer.8

On the other side of the Atlantic, it was Benjamin Franklin who personified this connection between science and the world of Freemasonry. In 1734, three years after he became a Mason in a lodge at Philadephia’s Tun Tavern, Franklin re-edited and published James Anderson’s work The Constitutions of the Free-Masons, likely the first Masonic book printed in America. That same year Franklin was elected Grand Master of Masons in Pennsylvania.9 In 1743, he founded the American Philosophical Society, the country’s first learned society, modeled after the Royal Society of London, among whose members numerous Freemasons can be found. Franklin was representative of an emphasis within American Freemasonry, particularly in the period after the Revolution, on learning and the promotion of useful knowledge.

Fig. 1: Illustration (late 19th century) depicting the Tun Tavern in Philadelphia, considered one of the birthplaces of American Freemasonry. Benjamin Franklin would become a Master Mason in this tavern in 1731. Courtesy of the Library of Congress

Masonic ties have thus not only been influential in the world of commerce or politics but also within the global network of science, where they have built useful networking systems.10 These were mainly “invisible networks”, consisting of powerful connections, though not always evident to those standing outside of them. Since Humboldt was a key person for the quest for science in the nineteenth century, establishing new standards of networking for the scholarly communication, aimed for the improvement of society, the question arises, having grown up during the expansion of Masonic beliefs in Europe, where would he position himself with regard to the postulates of Freemasonry?

The idea of Humboldt being connected, in one way or another, to Masonry, using the fraternity to initiate connections and facilitate his visit to the Americas might appear in the first place outside the realm of possibility.11 The later 18th and early 19th centuries saw the growth of Freemasonry across the globe, and, as such, Humboldt had ample opportunity to interact with its adherents. He may have first encountered Masonic circles in Prussia, where he grew up. In fact, his father Alexander Georg von Humboldt (1720–1779) is reported to have joined the lodge Petite Concorde in March 1754 and to have celebrated during several years the Johannisfest (the celebration of the eve of feast of St. John the Baptist, one of the “patron saints” of Freemasonry) on their country estate Tegel.12 Later Humboldt studied at the University of Göttingen and the Academy of Commerce in Hamburg, being both locations hubs of Masonry during his student years. In Weimar and Jena, important locations for the spread of Masonic ideas in Germany, the young Humboldt would frequent the circles around Goethe and Schiller, being the first a renowned Freemason. The same applies to Paris and Madrid, the cities where he prepared his further professional path that would take him to the New World. They were known for their marked Masonic activity and several of his key contacts there were Masons. Mariano Luis de Urquijo for instance, the Spanish Minister of State, who was instrumental in obtaining the permission from the monarch Charles IV for Humboldt to undertake his American expedition, was a Mason. Equally, in his travels in Spanish America, Humboldt had come in contact with Freemasons, particularly with those who shared his liberal outlook and critique of the exploitation of colonial societies. Finally, the main place of his short visit to the United States was Philadelphia, one of the centers of Masonic activity in the young country, especially among scientists, several of them members of the American Philosophical Society. However, it has to be noted that many of his acquaintances in both Philadelphia and Washington—chiefly Jefferson, Albert Gallatin, William Thornton, Benjamin Rush, and Charles Willson Peale—did not belong to any lodge, though are sometimes claimed as Freemasons. As with Humboldt, notable figures of talent and vision are often adopted as Masons by later generations.

It becomes evident that throughout his life, in different moments and in different locations, Humboldt would come in contact with numerous known Freemasons. Some had important political positions, such as Mariano Luis de Urquijo, and others became his close friends, such as François Arago in Paris or Karl August Varnhagen von Ense in Berlin, or else formed part of his extended correspondent network.13 Many of them were the foremost thinkers, who believed in the ideals of the Age of Reason and, just like the Prussian explorer himself, would direct their efforts towards an improvement of the society. His close relationship with these personalities, the parallels between his own ideals and the precepts of the craft, even the advantage of worldwide network to assist in his travels and studies, all suggest that Humboldt was not only claimed by Masons, but that he might have had sympathy or even a direct connection to Freemasonry. Upon his death in 1859, obituaries and memorials were published in Masonic publications, such as in the Freimaurer-Zeitung and a decade later, Humboldt was honored with a Masonic funeral procession in Philadelphia.14 But as yet, no proof for membership in a Masonic lodge can be found. Given the secrecy of the subject in Europe, it is indeed rather unlikely that potential approaches from Humboldt to any lodge would be documented for the public. In the United States, however, the situation was different, being Freemason in this country was nothing secret and members were publicly known as such. If the famous Prussian visitor had come to the United States as a member of a Masonic lodge, he would probably have joined a meeting at the lodges in in Philadelphia or in Washington and, in this case the lodges would have made sure the world would have known about it.

Even attendance as a visitor to a “properly tyled” lodge could be seen as a potential indication of membership, but as yet, no research effort has turned up a substantial connection to Freemasonry during Humboldt’s time in the United States. With the artist and naturalist Charles Wilson Peale as his guide, they visited Alexandria and travelled to Mount Vernon during Humboldt’s stay in the new capital city. There the Alexandria-Washington Lodge No. 22, the Masonic institution most directly connected to George Washington in that area, would have been a place to visit. Nevertheless, a search through the lodge’s minutes of that period shows no reference to the Prussian visitor. An examination of records for other established lodges in Washington, such as Federal or Potomac Lodges, could yet yield some connection. Likewise, as a center of American Freemasonry, Philadelphia would have offered Humboldt the opportunity to visit a lodge, perhaps even at the prestigious Lodge No. 2, where several of his new contacts at the American Philosophical Society were members. But while we learn from the records of this lodge that John Bache, Alexander Bartram, John Bartram and James Wilkinson had already been admitted in 1804, and Peter Du Ponceau, the secretary of the Society, would seek admission, again there is no mentioning of Humboldt.15 Further examinations of the records and minutes of other Philadelphia area lodges of the period could still potentially lead to different results. However, the most likely conclusion is that Humboldt was not affiliated with any lodge, not in the United States, but also not in Europe. Though many lodges would later claim his name, no lodge could apparently boast of having had Humboldt as a visitor. This in fact goes along with Humboldt’s general reservation towards social clubs or societies with specific rituals.

Though Humboldt’s visit to the United States was brief, it had a lasting impact in the American memory and imagination apparent from, if nothing else, the large number of places named after the Prussian, among them counties, towns, parks, rivers, mountains, etc.16 Also several American Masonic lodges bear his name, despite the fact that naming a lodge for a non-Mason is a rare honor, and a departure from normal protocol. Although he was not a member of the fraternity, American Freemasons readily adopted him as a source of inspiration. In general, the process of attributing Humboldt’s name to places and ideas happened for many different reasons, therefore, the question is what were the specific motives and moments for the Freemasons to connect their worldview with the Prussian naturalist?

Fig. 2: Hermann Humboldt Lodge No. 125 (https://www.hermann-humboldt-lodge-125.com)

The first lodge in the United States to be named after the famous explorer was the Humboldt Lodge No. 79, founded in Eureka, California, on June 30, 1854.17 Eureka is the seat of Humboldt County, established in 1853, in the same year as Fort Humboldt, overlooking the Humboldt Bay, which received its name in 1850.18 At some point before 1859, a lodge was created in New Orleans, Louisiana and named Alexander von Humboldt Lodge. Its membership was apparently largely German, though it was chartered under the Grand Orient of France, rather than the Grand Lodge of Louisiana. The lodge seems to have not survived the Civil War.19 After the war, in 1865, Humboldt Lodge No. 359 was founded in Philadelphia. A German-speaking lodge, it would go on to erect a monument to the Prussian scientist in 1869, the centennial of his birth.20 Humboldt’s centennial was celebrated across the nation with extensive commemoration festivities that made his name even more popular. Indeed, Humboldt Lodge No. 138, was founded in February of that same year in Rochester, New York, this time by another fraternal group, the Independent Order of Odd Fellows, which shared similar structures and precepts with Freemasonry, but whose members tended to middle and working classes.21 Humboldt Lodge No. 42, established by eighteen German-American Freemasons, was chartered the next year, on May 24, 1870, one of only six organized lodges in the state of Indiana, which held their ritual work in the German language.22 Finally, on June 12, 1901 the Humboldt Lodge No. 27 was chartered in Lovelock, Nevada.23 Interesting to note, this was not the last lodge named for Humboldt in North America. In 1973, Alexander von Humboldt Lodge was established in Mexico City, and performs its ritual in the German language as well.24

If Alexander von Humboldt was not a Freemason, what lies behind his adoption by Freemasons, particularly those in America? If his brief time in the US and his limited correspondence with Thomas Jefferson have, as James Howell contends, resulted in a disproportionate level of importance for Americans, what can explain this result and the clamor for Humboldt by Americans both then and now?25 Some Americans were primed to adopt Humboldt—Margaret Bayard Smith declared in a letter, that “an enlightened mind has already made him an American”—and Humboldt reciprocated, claiming to be “half an American.”26 Part of the answer certainly lies in his status and reputation, both during and after his life, as one of the foremost scientists of his day and an international celebrity. Two other related factors, though, help to explain a deeper connection for both Americans and Freemasons alike.

In April of 1794, Joseph Priestley, the renowned English scientist and prominent Dissenter and one of the most celebrated refugees of his day, set sail for his new home in America. On the eve of his departure, the Society of United Irishmen in Dublin wrote Priestley to take heart, for “you are going to a happier world, the world of Washington and Franklin”. America, they insisted, was a place where man “busied in rendering himself worthy of nature” and where “his ambition will be to subdue the elements … to make fire, water, earth, and air obey his bidding”. America was seen by many, both without and within, as a land where learning was valued, the sciences promoted for the common good, and where education was a civic virtue that cut through class and profession. Education and literacy were practically a secular religion in the early Republic, and Thomas Jefferson and other contemporaries believed the average American better read than their counterparts in Europe, particularly the yeoman farmer.27

This American focus on education and the sciences was reflected within Freemasonry. Just weeks before Priestley’s journey, a young DeWitt Clinton was installed as the master of Holland Lodge in New York City. In his address to the assembled brethren, the future governor highlighted the connections between Freemasonry and learning. “It is well known”, he said that Freemasonry “was at first composed of scientific and ingenious men, who assembled together to improve the arts and sciences”. Clinton advocated brethren use free hours for “mental improvement” and he declared “every Mason ought to enrich his mind with knowledge, not only because it better qualifies him to discharge the duties of the character, but because information and virtue are generally to be found in the same society”.28 Despite an emphasis on mathematics, geometry and the liberal arts, lodges were not themselves salons or academic lecture halls. But education, both for self-improvement and the public good, was certainly intertwined with early American Freemasonry. As Stephen Bullock notes, American Freemasons tended to focus more on the learning and scientific knowledge of their assumed antiquarian origins (Pythagoras and the ancient Greeks for instance) rather than claiming a hermetic and mystic heritage as was often emphasized by their European brethren. In Bullock’s words “the new view of Masonic history made the search for learning an important theme within American lodges”.29 Individual Freemasons and lodges played important roles in establishing free schools, libraries, and even museums in the early republic. A scholar of international renown, Humboldt’s visit to Philadelphia and Washington, while relatively brief, resonated against this cultural backdrop, and Freemasonry was at the vanguard.30

Another early American ideal bound Humboldt and America, and again Freemasonry played a prominent role. For many Americans of the period, education was not only vital to the perpetuation of a virtuous citizenry, and thus a strong republic, but also to the development a cosmopolitan outlook, something already percolating through American society. Seth Cotlar, in his examination of early American radicalism and political engagement in the 1790s, identifies a “popular cosmopolitan” outlook across many social and poltical circles, characterized by universalist views of mankind coupled with an engagement with the world beyond American shores.31 Many Americans envisioned themselves as George Washington did—a “member of an infant-empire, as a Philanthropist by character, and … as a Citizen of the great republic of humanity at large”.32 At its most radical, this envisioning of an educated republican as a “citizen of the world” trumped even national allegiance, though most Americans squared this cosmopolitan vision with a patriotic nationalism for a nascent republic that already seemed to embody that same vision.33

Fig. 3: Lithograph (c. 1867) depicting George Washington as a Master Mason and featuring two other important Masonic figures in America, Lafayette and Andrew Jackson. Courtesy of the Library of Congress

Few institutions in America better represented this cosmopolitan identity than Freemasonry. Dedicated to fraternal connections with an international brotherhood that stood apart from national allegiance, Freemasonry was constructed as cosmopolitan. It connected its members “with a wide-ranging network of like-minded fellows beyond their locality. Masons were strongly acculturated to the idea of belonging to a universal and affectionate brotherhood that extended beyond place and time”.34 A Mason was the embodiment of cosmopolitanism, someone who belonged, as the preacher John Andrews put it in his sermon on mutual kindness, “not to one particular place only, but to places without number, and in almost every quarter of the globe”.35 American Freemasons valued a cosmopolitan outlook, one where an educated gentleman was at home anywhere in the world and in any company, unbound by provincialism and prejudice, and Alexander von Humboldt would serve as an inspiration long after his brief sojourn in their nation.36

American Freemasons were not alone in their affinity for Alexander von Humboldt. Freemasons in his homeland used his legacy and reputation to burnish their own and establish a connection.37 Fewer Masonic lodges in Germany bear his name—among them a lodge of the Ancient Order of Druids, another 19th century fraternal group, which renamed itself Humboldt-Loge in 1887.38 However, a crucial insight is Humboldt’s treatment in German Masonic journals. Which aspects of his scientific work and his character would attract those circles? Two articles published in the Freimaurer-Zeitung during the commemoration year 1869 are of interest in this context. In one of them, under the title “Masons without apron” the author Moritz Alexander Zille argues that while some Freemasons lived and acted as if they had never used the Masonic apron, there were other men that behaved like Masons, without belonging to any lodge.39 Zille was a pedagogist, a vehement defender of a liberty of belief and religious position, who developed a broad Masonic activity and was known as a prolific Masonic author. The Freemasons thus recognized that also outside of their association there were persons who lived beyond the “prejudices of their religions” and acted in a humane and cosmopolitan manner. Independently if they carried an apron or if they formally became member of a masonic association, Zille continued with his arguments, they were considered to be a part of the Masonic Geistesbunde, their spiritual association. He welcomes these wise men, who “guide humanity to noble education and civilization by a gentle paternal hand”. Freemasons are proud of these honorary members, he states, they consider them “noble non-Masons to be equal to them” and recognize the principles of their cause also beyond the borders of their community. One person that according to the author stands out in this group as “real citizen of the world”, as an “ornament of humanity”, was Alexander von Humboldt.

A few months later, in the context of the commemoration of Humboldt’s birthday in September of the same year, a speech held by a Freemason was published in the same journal.40 This text specifically lays out the particular aspects that Freemasons appreciated in Humboldt, which would not differ from his perception within other groups in Germany.41 In this eulogy the author focuses on the Prussian’s contribution to the knowledge of the “perfect unity of natural practice,” and to the fact that he had shown to the people the unity of the world we are living in. Based on strict scientific practices, the explorer had described the most sublime of the physical and historical development, which is reflected in his significant last oeuvre Cosmos. He highlights in particular Humboldt’s holistic focus, his vision of humankind as a whole, his efforts to eradicate prejudices, independently of race, religion, nationality or color. It was Humboldt’s “service to humanity”, and his scientific justification of the humanistic ideal, what constituted a central argument for the author, given that this postulate was a key task for Freemasons.

Therefore the author considers it to be important to make his life known, and calls on all Freemasons to celebrate Humboldt’s name, independently if he was a formal member of Masonry or not. The famous world citizen, who believed in the progress and the uprising of human kind, who loved humanity should be incorporated within the Masonic community, he argues, given that as person he embodied masonic ideas and as scientist he provided the scholarly fundament for their principles.

Another masonic journal, the Mitteilungen aus dem Verein Deutscher Freimaurer published an article in 1882, which offers an interesting insight regarding Humboldt’s significance for Freemasonry.42 Here the Prussian is presented as one of the “most universal spirits of our nation”, as a person “that serves the highest merit for the goals of Freemasonry”, with a character free of selfishness who “deserves the admiration of masonic world to a special degree”. In the eyes of the author, Humboldt was the right master builder at the temple of humanity, whose spirit will remain in the world, and whom “every mason should feel inclined to celebrate”. The author attributes him a Masonic heart and describes him as “greatest benefactor of human kind”. In particular, he praises him for his popularization of the sciences, for his liberation of mankind from prejudices and delusion and his fight against hate and persecution. Since those are also the postulates of Masonic humanism, this turns him into a role model also for Masons. The Prussian had used the large part of his wealth for the purposes of charity and he promoted aspiring talents through encouraging responsiveness. In addition, he fostered the free development of the human spirit, independent studies and aspirations and therefore, concludes the author, “this genius should be the leader of all Freemasons”. The name of Humboldt adorns each lodge, he argued, and thus Masons should feel the obligation to prepare a yearly celebration of the Prussian explorer, to commemorate him as one of them and to consider him to be a “connecting element with the great historic development of human kind”.

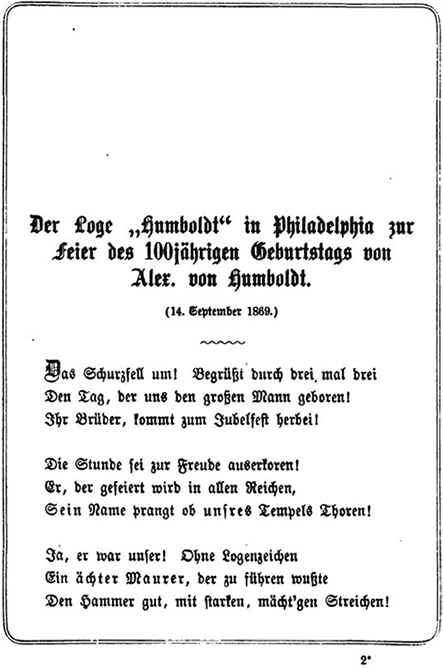

One last literary connection links Humboldt to German Freemasonry, and as such, to the rest of the fraternal world. The merchant and poet Friedrich Emil Rittershaus (1834–1897) was the co-founder and master of the lodge “Lessing” in Barmen (1878 to 1886) and longtime president of the Association of German Freemasons.43 In the context of the commemoration in 1869 he became prolific and wrote several pieces on the explorer. He published a short article about the celebrations on both sides of the Atlantic in the German journal Die Gartenlaube,44 produced a poem titled “For the Humboldt Festival in America” that was put to press in New York,45 and he dedicated another composition to the Humboldt Lodge in Philadelphia, to be used in the context of the festivities to celebrate his birthday.46 The first poem is a general praise of Humboldt, where Masonic connotations can be read between the lines, without including more specific statements. Humboldt, whom he calls “champion of the sciences” and “a citizen of all worlds”, was considered as “one of ours, of our land”, who now, in Rittershaus’ somewhat nationalist twist, gives the opportunity to see again a “German’s honors rise”. The second poem however, the one written for the Humboldt lodge, is a clear presentation of the Prussian explorer as a “mason in spirit” and reveals what Masons were fascinated about him. “Yes, he was ours!” Rittershaus argues here as well, but this time not referring to the German nations, but to the world of Freemasons. Without the symbol of any lodge he was considered a “real bricklayer, who knew how to lead the hammer well, with strong, powerful strokes!” He tore off the “curtain’s rotten folds of superstition” and was consecrated to building the “giant dome of knowledge”, while leading humanity to the free thinking and fighting against the injustice in the world.

Fig. 4: Emil Rittershaus, Freimaurerische Dichtungen (Leipzig: J. G. Findel, 1870), 19–22. (http://freimaurer-wiki.de/index.php/Rittershaus_Freimaurerische_Dichtungen_2).

All these examples show repeated arguments used by Freemasons in favor of Humboldt, that reveal in which specific aspect they considered him to be helpful to their causes. It becomes evident that also in those circles he was considered not to be a formal member. However, given his prominence, his influence, but his outstanding personality, Masons converted him in a role model and example to follow. Humboldt was seen as the Grand Master of Natural Sciences, who guided natural sciences into new paths.47 However, his mission did not end here, it was oriented to the much larger goals to transform the society according to Enlightenment ideals, particularly in the young United States, where Freemasonry was an important factor in the transformation of American society and culture.48 It is thus no surprise that Humboldt was attributed an important role to shape the nations ideas of liberty, equality and the pursuit of knowledge.

The famous Prussian’s impact in the United States was too significant, and his own ideals were in many senses too close to Masonic goals, not to be touched upon by Freemasons. In the end it was not decisive if the explorer himself had approached those groups, if he had joined any lodge or if he had contemplated in doing so. It was not even important how he personally positioned himself towards Freemasonry, since this appropriation was not based on any comment by Humboldt, as it would happen with other topics, when certain of his reflections were taken as proves of his moral support for specific causes. Freemasons considered that they shared same ideas, he was useful to them and they thus considered him to form part of their group, adopting him as a Mason “without apron”.

It is difficult to find any reflection or judgement from Humboldt himself concerning Freemasonry. It seems that as with religion, he also preferred to keep his opinion of fraternalism to himself. Besides occasional comments on the negative effects of Catholic dogmatism, he chose to leave religion in its broader connection out of his science. The fact that Humboldt did not express religious convictions in his works, as the primary source of authority and legitimacy, can be understood in connection to the Enlightenment postulates. His silence on Freemasonry might have had similar motivations. Indeed, it might have also been the lack of religiousness as fundament for his work that would help to open the doors for his “adoption” by Freemasonry. It is important to note the fact that during his lifetime, Humboldt could have protested against this “adoption,” as he would do whenever he saw that his name was used for causes that he would not support.

Being based on Enlightenment philosophy, Freemasonry stands for man’s search for wisdom, brotherhood and charity; it was also viewed as an enlightened conduit for self-improvement, religious tolerance and freedom. Men would join for multiple reasons—apart from philosophical affinities, membership was often beneficial for their social and business activities, expanding social and professional networks. For Humboldt, however, there was not really a reason to join a lodge, since a membership would not have added much to his outstanding fame nor to the scope of his scientific project. As a successful and internationally renowned scholar, he lived a quite self-determined life, perfectly able to create his own networks and, given his name and fame, many groups, associations or institutions were readily open to him. Moreover, he was extremely busy with his ambitious global projects and tended to subordinate everything else to scholarly goals. Hence, he would probably not have had much time to dedicate to additional causes. In any case, he might have preferred to use other intellectual or social platforms, rather than lodges. Despite certain similarities of some of their goals and despite numerous opportunities, there was no necessity for him to establish a formal connection to Freemasonry.

Humboldt’s Masonic “assimilation” takes on an interesting dimension, if we take the timing into account. It is in the second half of nineteenth century when can we find most of the Masonic references to him and where many American lodges were named for him. This does not mean that he was of less use for Masonic communities during his lifetime. But in the case of American Freemasons, the explanation can be connected to the trajectory of Masonry during the mid-19th century. Coming not long after Humboldt’s heralded American visit, the Anti-Masonic period of the late 1820s and 1830s saw Freemasonry attacked from different sides, as alternately elitist and immoral, resulting in a decline in membership and the closure of lodges. Freemasonry’s revival in the 1840s and 1850s was predicated on a new vision and interpretation of the Craft’s values, emphasizing American identity through a connection with Washington and the Founders, focusing on biblical wisdom over esotericism, and committing to temperance and regularity.49

At the same time, waves of increased immigration from Germany, Ireland, and other Western European countries brought new Americans who were drawn to fraternalism. Newcomers either joined established organizations like Freemasonry and the Oddfellows, or else used the structures of fraternalism to create their own organizations, such as B’nai B’rith and the Ancient Order of Hibernians, that were predicated their language and heritage.50 The failed revolutions of 1848, in particular, brought an increased influx of German immigrants to America, nearly one million during the 1850s alone, on top of significant German populations that had been established in America for decades before. German settlers’ attempts to remain culturally distinct, even isolated, within an ever-expanding American nation were challenged by German-American leaders like Carl Schurz who saw assimilation and civic participation as paramount.51 For German-Americans, fraternal organizations were helpful toward these larger goals of integration, assimilation, and establishment in their new society, while still preserving a form of connection with and pride in their cultural heritage. Humboldt, beloved in both America and their homeland, was an ideal figure to honor and emulate, along with other cultural figures such as Mozart and Goethe, who would also serve as lodge namesakes in the period. By 1850, Masonic membership had recovered, and by 1860, the eve of the Civil War, the number of America Freemasons had increased to nearly 200,000, setting the stage of a golden age of fraternalism in the United States between 1865 and 1910.52 For German-Americans of this period, the Prussian served as an identifying cultural figure, one that linked the two nations, and whether Masons or not, they played significant roles in the organization of Humboldt centennials in the US.53

In examining the connections between Alexander von Humboldt and Freemasonry, we come not only to the conclusion that he was not a Freemason, but also that a formal membership in Freemasonry would not have truly mattered to his worldwide success and acclaim. Nevertheless, Freemasons made of Humboldt what they needed: he was the personification of their Enlightenment-era ideals and thus a perfect fit for their goals. With his work he delivered the scientific base for many of the Masonic postulates and with his strong humanistic ideals, not based on any religion, he made it easy to be appropriated.54 It is thus not surprising that they incorporated him into their worldview and considering him to be one of them and claimed by them as a “Mason in spirit” or a “Mason without apron,” just as other groups tried to connect him to their respective interests. Given his broad concerns, his global aspirations and his holistic approach to science, Humboldt offered a platform for many different types of projections and was used for very distinct purposes. Well known is how his comments and writings have been used in support of the independence movements in Spanish America, less known is how the same happened for claims of Manifest Destiny in the United States, and for other causes greater than that of fraternalism, no matter how broadly realized.55

However, though acclaimed by German Freemasons, particularly as a fellow German who embodied a Masonic ideal, Humboldt seems to have held a greater potential for American Masons. In addition, Humboldt foresaw the future development and the potential needs of the young republic with regard to the exploration of the American West and claimed the need of a thorough study of nature, the significance of scientific progress and technological advancement as well as international trade and communication strategies.56 Though neither, Humboldt was held up as a perfect Freemason as well as a “perfect American”, or at least, half American. Yet, Humboldt provided even more potential connections, as a unifying figure between Germans and Americans, between the centers of learning at the East Coast and the broad territories to explore in the American West, between scientific pursuits and political strategy. In addition, from the American side he was also seen as a gate-keeper to European knowledge. The fact that he offered an even larger projection screen through his international scope as European and cosmopolitan scholar is another factor that contributed to his appropriation through different groups, but especially American Freemasonry.

Andrews, John. “A sermon on the importance of mutual kindness: preached at St. James’s, Bristol, December 27, 1789, being the anniversary of St. John the Evangelist, before the brethren of Lodge no. 25.” (Philadelphia: William Young, 1790).

Barratt, Norris S. and J. F. Sachse. Freemasory in Pennsylvania, 1727–1907, vol. I (Philadelphia, Grand lodge F. & A. M. Penn, 1909).

Beadie, Nancy. Education and the Creation of Capital in the Early American Republic (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2010).

Beck, Hanno. “Zur Humanität Alexander von Humboldts”, Eleusis. Organ des Deutschen Obersten Rats der Freimaurer des Alten und Angenommenen Schottischen Ritus, 33 (1978), pp. 260–265.

Br[uder Freimaurer] Redner der Loge. “Zur goldnen Krone”, “Erinnerung an Alexander von Humboldt”, Freimaurer-Zeitung, no. 38, 18 September 1869, pp. 297–302.

Bullock, Stephen. Revolutionary Brotherhood: Freemasonry and the transformation of the American social order 1730–1840 (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 1996).

Caspar, Gerhard. “A Young Man from “ultima Thule” Visits Jefferson: Alexander Von Humboldt in Philadelphia and Washington.” Proceedings of the American Philosophical Society 155, no. 3 (2011), pp. 247–62.

Clinton, DeWitt. “An Address Delivered Before Holland Lodge, December 24, 1793.” (New York: Francis Childs and John Swaine, 1794).

Cotlar, Seth. Tom Paine’s America: The Rise and Fall of Transatlantic Radicalism in the Early Republic (Charlottesville: University of Virginia Press, 2011).

Daniel, James W. Masonic Networks and Connections (London: The Library and Museum of Freemasonry, 2007).

Dassow Walls, Laura, The Passage to Cosmos. Alexander von Humboldt and the Shaping of America (Chicago and London: University of Chicago Press, 2009).

Daum, Andreas, “Celebrating Humanism in St. Louis: The Origins of the Humboldt Statue in Tower Grove Park, 1859–1878.” Gateway Heritage 15.2. (Fall 1994), pp. 48–58.

David G. Hackett. That Religion in Which All Men Agree: Freemasonry in American Culture (Berkeley: University of California Press, 2014).

Dr. Beyer. “Alexander von Humboldt und seine Bedeutung für das freie Maurerthun”, Mitteilungen aus dem Verein Deutscher Freimaurer 1881–1882 (Leipzig: Naumann, 1882), pp. 74–85.

Elliott, Paul and Stephen Daniels. “The ‘School of True, Useful and Universal Science’? Freemasonry, Natural Philosophy and Scientific Culture in Eighteenth-Century England”, The British Journal for the History of Science, 39: 2 (June 2006), pp. 207–229.

Ette, Ottmar. Alexander Humboldt. Das Buch der Begegnungen: Menschen – Kulturen – Geschichten. Aus den Amerikanischen Reisetagebüchern (München: Manesse, 2018).

Franklin, Benjamin. Autobiography, Poor Richard, Letters (New York: D. Appleton & Co., 1904).

Friis, Hermann R. “Baron Alexander von Humboldt’s Visit to Washington.” Records of the Columbia Historical Society 44 (1963), pp. 1–35.

Gerlach, Karlheinz. “Freimaurer im friderizianischen Preußen (Part VIII). Alexander Georg von Humboldt (1720–1779)”. Bundesblatt 94:5 (1996), pp. 34–37.

Goetzmann, William H, New Lands, New Men: America and the Second Great Age of Discovery (New York, N. Y.: Viking, 1986).

Hagger, Nicholas. The Secret Founding of America: the Real Story of Freemasons, Puritans and the Battle for the New World (London: Watkins Publishing, 2007).

Harland-Jacobs, Jessica. “‘Hands across the Sea’: The Masonic Network, British Imperialism, and the North Atlantic World”, Geographical Review, 89:2 (April 1999), pp. 237–253.

Hoffmann, Stefan-Ludwig. Die Politik der Geselligkeit: Freimaurerlogen in der Deutschen Bürgergesellschaft 1840–1918 (Göttingen: Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht, 2000).

Bruce Hogg and Diane Clements. “Freemasons and the Royal Society.” (Library and Museum of Freemasonry, London, 2010), http://freemasonry.london.museum/it/wp-content/resources/frs_freemasons_complete_jan2012.pdf (last access on 31 October 2018).

Hoppen, K. Theodore. “The Nature of the Early Royal Society II.” The British Journal for the History of Science, Vol. 9, No. 3 (Nov. 1976).

Howell, James F. “Recasting the Significant: The Transcultural Memory of Alexander von Humboldt’s Visit to Philadelphia and Washington, D. C.” Humanities 2016, 5(3), pp. 1–9.

Jacob, Margaret C. Living the Enlightenment: Freemasonry and Politics in Eighteenth-century Europe (New York: Oxford University Press, 2016).

Jones, Maldwyn Allen, American Immigration, 2nd ed. (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1992).

Keghel Alain de. American Freemasonry: Its Revolutionary History and Challenging Future. Rochester (Vermont: Inner Traditions, 2017).

Large, Arlen J., ‘The Humboldt connection’, We Proceeded On, 16:4 (November 1990), pp. 4–12.

Lemay, J. A. Leo. The Life of Benjamin Franklin Volume 2: Printer and Publisher 1730–1747 (Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 2006).

Lennhoff, Eugen, Dieter A. Binder and Oskar Posner. Internationales Freimaurer-Lexikon (Munich: Herbig, 2000).

Lynch, Jack. “‘Every Man Able to Read’: Literacy in Early America.” Colonial Williamsburg Journal, Winter 2011, http://www.history.org/Foundation/journal/Winter11/literacy.cfm (last access on 31 October 2018).

Moore, William D. and Hamilton, John D. “Washington as the Master of his Lodge: History and Symbolism of a Masonic Icon” in George Washington American Symbol, Barbara J. Minick, ed. (New York: Hudson Hill Press, 1999).

Nollendorfs, Cora Lee. “Alexander von Humboldt Centennial Celebrations in the United States: Controversies concerning His Work”. Monatshefte 80, no. 1 (1988): pp. 59–66.

Oppitz, Ulrich-Dieter. “Der Name der Brüder Humboldt in aller Welt”. In: Alexander von Humboldt, Werk und Weltgeltung, edited by Heinrich Pfeiffer (Munich: R. Piper, 1969), pp. 277–429.

Proceedings of the Grand Lodge of the A. F. & A. M. of the State of North Dakota (Fargo: Nugent & Brown, 1793).

Rebok, Sandra. Jefferson and Humboldt: A Transatlantic Friendship of the Enlightenment (Charlottesville: University of Virginia Press, 2014).

Rebok, Sandra, “Humboldt’s exploration at a distance”, Worlds of Natural History, edited by H. Curry, N. Jardine, J. A. Secord, and Emma C. Spary (Cambridge University Press, 2018), pp. 319–334.

Révauger, Cécile, Black Freemasonry (Rochester, VT: Inner Traditions, 2016).

Rittershaus, Emil. “Fest-Gedicht für die Humboldt-Feier in Amerika am 14. September 1869”, translated by Kate Kroeker-Freiligrath (New York: L. W. Schmidt, 1869), re-printed in: Rex Clark and Oliver Lubrich, Transatlantic Echoes: Alexander von Humboldt in World Literature (New York: Berghahn books, 2012), pp. 181–183.

Rittershaus, Emil. “Zum Humboldtfest in der alten und der neuen Welt,” Die Gartenlaube, 37 (1869), pp. 577–578.

Rittershaus, Emil. Freimaurerische Dichtungen (Leipzig: J. G. Findel, 1870).

Ruitt, John Towill. Life and Correspondence of Joseph Priestley (London: R. Hunter, 1832).

Rupke, Nicolaas A. Alexander von Humboldt: A Metabiography (Frankfurt: Peter Lang, 2005).

Sachse, Julius F. Benjamin Franklin as a Freemason (Lancaster, PA: New Era Print Co., 1906).

Sachse, Julius F. Washington’s Masonic Correspondence (Philadelphia: Grand Lodge of Pennsylvania, 1915).

Schoenwaldt, Peter. “Alexander von Humboldt und die Vereinigten Staaten von Amerika.” In: Alexander von Humboldt: Werk und Weltgeltung, edited by Heinrich Pfeiffer (Munich: R. Piper, 1969), pp. 431–482.

Schwarz, Ingo. “Alexander von Humboldt’s Visit to Washington and Philadelphia, His Friendship with Jefferson, and His Fascination with the United States.” In: “Proceedings: Alexander von Humboldt’s Natural History Legacy and Its Relevance for Today,” special issue, Northeastern Naturalist 1 (2001), pp. 43–56.

Schwarz, Ingo. “Das Album der Humboldt-Lokalitäten in der Neuen Welt”. In: Magazin für Amerikanistik 20 (1996), n. 2, pp. 64–66 (part 1); n. 3, pp. 52–54 (part 2).

Spingola, Deanna. The Ruling Elite: a Study in Imperialism, Genocide and Emancipation (Unknown publishing place: Trafford Publishing, 2011).

Tabbert, Mark A. American Freemasons: Three Centuries of Building Communities (Lexington, Mass.: National Heritage Museum, 2005).

Terra, Helmut de. “Motives and consequences of Alexander von Humboldt’s visit to the United States 1804”. In: Proceedings of the American Philosophical Society, 104.1960, pp. 314–316, 1960, pp. 314–316.

Walls, Laura Dasso. The Passage to Cosmos: Alexander von Humboldt and the shaping of America (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2009).

Weisberger, R. William. Speculative Freemasonry and the Englightenment, 2nd Ed. (Jefferson, NCL: McFarland & Co. Inc., 2017).

Wood, Gordon. Empire of Liberty: a History of the Early Republic, 1789–1815 (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2009).

Michael Zeuske. “Vater der Unabhängigkeit? – Humboldt und die Transformation zur Moderne im spanischen Amerika”. In: Alexander von Humboldt. Aufbruch in die Moderne, ed. Ette, Ottmar; Hermanns, Ute; Scherer, Bernd M.; Suckow, Christian. (Berlin: Akademie Verlag 2001), pp. 179–224.

Zille, Moritz. “Die Freimaurer ohne Schurz”, Freimaurer-Zeitung, no. 13, 27 March 1869, pp. 97–99.

* This article was elaborated in the context of a Baird Society Resident Scholar fellowship awarded by the Smithsonian Libraries in Washington DC. Research has been carried out in the Dibner History of Science Library and the American History Library at the Smithsonian Institution as well as the International Center for Jefferson Studies in Charlottesville, Virginia. I would like to thank the staff of both institutions, who has been very helpful for this research.

1 Gordon Wood. Empire of Liberty: a History of the Early Republic, 1789–1815 (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2009), p. 51.

2 Mark A. Tabbert. American Freemasons: Three Centuries of Building Communities. (Lexington, Mass.: National Heritage Museum, 2005), pp. 16–24, 33–34. Alain de Keghel, American Freemasonry: Its Revolutionary History and Challenging Future. Rochester, Vermont: Inner Traditions, 2017. John Hammill, The Craft: A History of English Freemasonry (Wellingborough, UK: Crucible, 1986).

3 In a letter to his father in 1738, early American Freemason Benjamin Franklin tried to allay his mother’s concerns with his participation in the fraternity, remarking that members of the craft “have no principles or practices that are inconsistent with religion and good manners”. Benjamin Franklin. Autobiography, Poor Richard, Letters (New York: D. Appleton & Co., 1904), pp. 254–255.

4 Nicholas Hagger. The Secret Founding of America: the Real Story of Freemasons, Puritans and the Battle for the New World (London: Watkins Publishing, 2007); David G. Hackett, That Religion in Which All Men Agree: Freemasonry in American Culture (Berkeley: University of California Press, 2014). For Franklin’s career in Freemasonry see Julius F. Sachse, Benjamin Franklin as a Freemason (Lancaster, PA: New Era Print Co., 1906) and R. William Weisberger, Speculative Freemasonry and the Englightenment, 2nd Ed. (Jefferson, NCL: McFarland & Co. Inc., 2017). For Washington’s involvement with Freemasonry, see Julius F. Sachse, Washington’s Masonic Correspondence (Philadelphia: Grand Lodge of Pennsylvania, 1915).

5 K. Theodore Hoppen. “The Nature of the Early Royal Society II.” The British Journal for the History of Science, Vol. 9, No. 3 (Nov. 1976), p. 268n.

6 Bruce Hogg and Diane Clements. “Freemasons and the Royal Society.” (Library and Museum of Freemasonry, London, 2010), http://freemasonry.london.museum/it/wp-content/resources/frs_freemasons_complete_jan2012.pdf (last access on 31 October 2018).

7 Tabbert, American Freemasons, p. 25.

8 Ette, Ottmar. Alexander Humboldt. Das Buch der Begegnungen: Menschen – Kulturen – Geschichten. Aus den Amerikanischen Reisetagebüchern (München: Manesse, 2018), p. 8.

9 Franklin’s early interest in Freemasonry and his Masonic career are well covered in chapter three of J. A. Leo Lemay. The Life of Benjamin Franklin Volume 2: Printer and Publisher 1730–1747 (Philadelphia: Univ. of Pennsylvania Press, 2006), pp. 83–92.

10 Jessica Harland-Jacobs. “‘Hands across the Sea’: The Masonic Network, British Imperialism, and the North Atlantic World”, Geographical Review, 89:2 (April 1999), pp. 237–253; James W. Daniel. Masonic Networks and Connections (London: The Library and Museum of Freemasonry, 2007); Paul Elliott and Stephen Daniels. “The ‘School of True, Useful and Universal Science’? Freemasonry, Natural Philosophy and Scientific Culture in Eighteenth-Century England”, The British Journal for the History of Science, 39: 2 (June 2006), pp. 207–229.

11 The Italian explorer Giacomo Beltrami, a near contemporary of Humboldt, and his partner Lawrence Taliaferro, a US Indian agent, likely bonded over their fraternal connection, potentially using them to expedite their efforts to the discovery the headwaters of the Mississippi River in 1823.

12 Karlheinz Gerlach. “Freimaurer im friderizianischen Preußen (Part VIII). Alexander Georg von Humboldt (1720–1779)”. Bundesblatt 94:5 (1996), pp. 34–37.

13 Eugen Lennhoff, Dieter A. Binder and Oskar Posner. Internationales Freimaurer-Lexikon (Munich: Herbig, 2000).

14 See article on the front page of the Philadelphia Inquirer, 14 Sept. 1869.

15 Norris S. Barratt and J. F. Sachse. Freemasory in Pennsylvania, 1727–1907, vol. I (Philadelphia, Grand lodge F. & A. M. Penn, 1909).

16 Ulrich-Dieter Oppitz. “Der Name der Brüder Humboldt in aller Welt”. In: Alexander von Humboldt, Werk und Weltgeltung, edited by Heinrich Pfeiffer (Munich: R. Piper, 1969), pp. 277–429. Ingo Schwarz, “Das Album der Humboldt-Lokalitäten in der Neuen Welt”. In: Magazin für Amerikanistik 20 (1996), n. 2, pp. 64–66 (part 1); n. 3, pp. 52–54 (part 2).

17 http://humboldtlodge79.org/humboldt-lodge-no-79-free-accepted-Masons/ (last access on 27 October 2018).

18 Ulrich-Dieter Oppitz. “Der Name der Brüder Humboldt in aller Welt”. In: Alexander von Humboldt, Werk und Weltgeltung, edited by Heinrich Pfeiffer (Munich: R. Piper, 1969), pp. 277–429.

19 Proceedings of the Grand Lodge of the A. F. & A. M. of the State of North Dakota (Fargo: Nugent & Brown, 1793) p. 126.

20 Information generously facilitated by Prof. Frank Trommler (University of Pennsylvania), based on his lecture “Wisdom! Strength! Fraternity! Philadelphia’s Still Existing Hermann Lodge of 1810”, held at the 33rd Annual Symposium of the Society of German-American Studies 2009 in New Ulm.

21 https://www.facebook.com/pg/Humboldt-Lodge-138-IOOF-148716114818/about/ (last access on 27 October 2018).

22 http://humboldt42.com (last access on 27 October 2018).

23 http://nvmasons.org/lodges/humboldt-27/ (last access on 27 October 2018).

24 “The Grand Lodge A. F. & A. M. of Canada in the Province of Ontario, Proceedings, 1977”, p. 28.

25 James F. Howell. “Recasting the Significant: The Transcultural Memory of Alexander von Humboldt’s Visit to Philadelphia and Washington, D. C.” Humanities 2016, 5(3), 49, pp. 1–2.

26 Laura Dasso Walls. The Passage to Cosmos: Alexander von Humboldt and the shaping of America (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2009), pp. 105, ix.

27 A good summary of studies into literacy levels in colonial America and the Early Republic can be found in Jack Lynch. “‘Every Man Able to Read’: Literacy in Early America.” Colonial Williamsburg Journal, Winter 2011, http://www.history.org/Foundation/journal/Winter11/literacy.cfm (last access 31 October 2018).

28 DeWitt Clinton. “An Address Delivered Before Holland Lodge, December 24, 1793.” (New York: Francis Childs and John Swaine, 1794), p. 4.

29 Stephen Bullock. Revolutionary Brotherhood: Freemasonry and the transformation of the American social order 1730–1840 (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 1996), pp. 145–150.

30 Detailed information on Humboldt’s visit to the United States can be found in: Sandra Rebok. Jefferson and Humboldt: A Transatlantic Friendship of the Enlightenment. Charlottesville: University of Virginia Press, 2014; Hermann R. Friis. “Baron Alexander von Humboldt’s Visit to Washington.” Records of the Columbia Historical Society 44 (1963), pp. 1–35; Ingo Schwarz. “Alexander von Humboldt’s Visit to Washington and Philadelphia, His Friendship with Jefferson, and His Fascination with the United States”. In: “Proceedings: Alexander von Humboldt’s Natural History Legacy and Its Relevance for Today,” special issue, Northeastern Naturalist 1 (2001), pp. 43–56; Helmut de Terra. “Motives and consequences of Alexander von Humboldt’s visit to the United States 1804”. In: Proceedings of the American Philosophical Society, 104.1960, pp. 314–316, 1960, pp. 314–316; Peter Schoenwaldt. “Alexander von Humboldt und die Vereinigten Staaten von Amerika.” In: Alexander von Humboldt: Werk und Weltgeltung, edited by Heinrich Pfeiffer (Munich: R. Piper, 1969), pp. 431–482; Gerhard Caspar. “A Young Man from “ultima Thule” Visits Jefferson: Alexander Von Humboldt in Philadelphia and Washington.” Proceedings of the American Philosophical Society 155, no. 3 (2011), pp. 247–262.

31 Seth Cotlar. Tom Paine’s America: The Rise and Fall of Transatlantic Radicalism in the Early Republic (Charlottesville: University of Virginia Press, 2011), p. 50–51.

32 “From George Washington to Lafayette, 15 August 1786,” Founders Online, National Archives, last modified June 13, 2018, http://founders.archives.gov/documents/Washington/04-04-02-0200 (last access on 27 October 2018).

33 Cotlar p. 49–51. As an example of a truly radical cosmopolitan appeal, Cotlar uses the address by Tunis Wortman before the Tammany Society in 1796. See Tunis Wortman, “An Oration on the Influence of Social Institution Upon Human Morals and Happiness” (New York: C. C. Van Alan & Co., 1796).

34 Nancy Beadie. Education and the Creation of Capital in the Early American Republic (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2010), p. 164.

35 John Andrews. “A sermon on the importance of mutual kindness: preached at St. James’s, Bristol, December 27, 1789, being the anniversary of St. John the Evangelist, before the brethren of Lodge no. 25.” (Philadelphia: William Young, 1790).

36 African-American participants in Prince Hall Freemasonry would have further identified with Humboldt’s later outspoken critique of slavery and support for abolition in the US. While white Freemasonry was ambivalent on the issue of slavery and generally left the matter to individual conscience, many African-American Freemasons were also leading abolitionists who saw their fraternal activity as a way of raising awareness of the struggle against slavery. For an account of this activism, see Cécile Révauger, Black Freemasonry (Rochester, VT: Inner Traditions, 2016), pp. 36–55.

37##KlausJochen1 Stefan-Ludwig Hoffmann. Die Politik der Geselligkeit: Freimaurerlogen in der Deutschen Bürgergesellschaft 1840–1918 (Göttingen: Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht, 2000). Margaret C Jacob. Living the Enlightenment: Freemasonry and Politics in Eighteenth-century Europe (New York: Oxford University Press, 2016).

38 http://www.druiden-orden.de/geschichte.html (last access on 27 October 2018).

39 Moritz Zille. “Die Freimaurer ohne Schurz”, Freimaurer-Zeitung, no. 13, 27 March 1869, pp. 97–99.

40 Br[uder Freimaurer] Redner der Loge. “Zur goldnen Krone”, “Erinnerung an Alexander von Humboldt”, Freimaurer-Zeitung, no. 38, 18 September 1869, pp. 297–302.

41 Nicolaas Rupke offers an excellent analysis of different forms of appropriation of Humboldt in German history: Nicolaas A. Rupke. Alexander von Humboldt: A Metabiography (Frankfurt: Peter Lang, 2005).

42 Dr. Beyer. “Alexander von Humboldt und seine Bedeutung für das freie Maurerthun”, Mitteilungen aus dem Verein Deutscher Freimaurer 1881–1882 (Leipzig: Naumann, 1882), pp. 74–85.

43 Emil Rittershaus. Freimaurerische Dichtungen (Leipzig: J. G. Findel, 1870).

44 Emil Rittershaus. “Zum Humboldtfest in der alten und der neuen Welt,” Die Gartenlaube, 37 (1869), pp. 577–578, https://de.wikisource.org/wiki/Zum_Humboldtfest_in_der_alten_und_neuen_Welt (last access on 27 October 2018).

45 Emil Rittershaus. “Fest-Gedicht für die Humboldt-Feier in Amerika am 14. September 1869”, translated by Kate Kroeker-Freiligrath (New York: L. W. Schmidt, 1869), re-printed in: Rex Clark and Oliver Lubrich. Transatlantic Echoes: Alexander von Humboldt in World Literature (New York: Berghahn books, 2012), pp. 181–183.

46 Emil Rittershaus. Freimaurerische Dichtungen, 1870, pp. 19–22, http://freimaurer-wiki.de/index.php/Rittershaus_Freimaurerische_Dichtungen_2 (last access on 27 October 2018).

47 Deanna Spingola. The Ruling Elite: a Study in Imperialism, Genocide and Emancipation (Unknown publishing place: Trafford Publishing, 2011), p. 88.

48 Steven C. Bullock. Revolutionary Brotherhood: Freemasonry and the transformation of the American social order, 1730–1840 (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 1996).

49 William D. Moore and John D. Hamilton, “Washington as the Master of his Lodge: History and Symbolism of a Masonic Icon” in George Washington American Symbol, Barbara J. Minick, ed. (New York: Hudson Hill Press, 1999), p. 78.

50 Tabbert, American Freemasons, pp. 71.

51 Maldwyn Allen Jones, American Immigration, 2nd ed. (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1992), pp. 106–107. See also the Library of Congress’ “Germans in America” timeline https://www.loc.gov/rr/european/imde/germchro.html (last access on 31 October 2018).

52 Tabbert, American Freemasons, pp. 78.

53 For information on how the centennial of Humboldt’s birth was celebrated in different places in the United States, see: Cora Lee Nollendorfs. “Alexander von Humboldt Centennial Celebrations in the United States: Controversies concerning His Work”. Monatshefte 80, no. 1 (1988): pp. 59–66; Laura Dassow Walls, The Passage to Cosmos. Alexander von Humboldt and the Shaping of America (Chicago and London: University of Chicago Press, 2009), p. 304–305. Andreas Daum, “Celebrating Humanism in St. Louis: The Origins of the Humboldt Statue in Tower Grove Park, 1859–1878.” Gateway Heritage 15.2. (Fall 1994), pp. 48–58.

54 Hanno Beck. “Zur Humanität Alexander von Humboldts”, Eleusis. Organ des Deutschen Obersten Rats der Freimaurer des Alten und Angenommenen Schottischen Ritus, 33 (1978), pp. 260–265.

55 Michael Zeuske. “Vater der Unabhängigkeit? – Humboldt und die Transformation zur Moderne im spanischen Amerika”. In: Alexander von Humboldt. Aufbruch in die Moderne, ed. Ette, Ottmar; Hermanns, Ute; Scherer, Bernd M.; Suckow, Christian. Berlin: Akademie Verlag 2001, pp. 179–224; Dassow Walls, The Passage to Cosmos, 105; Goetzmann, William H, New lands, new men: America and the second great age of discovery (New York, N. Y.: Viking, 1986), p. 98.

56 Sandra Rebok, “Humboldt’s exploration at a distance”, Worlds of Natural History, edited by H. Curry, N. Jardine, J. A. Secord, and Emma C. Spary (Cambridge University Press, 2018), p. 319–334; Arlen J. Large, ‘The Humboldt connection’, We Proceeded On, 16:4 (November 1990), pp. 4–12.