Miguel Ángel Puig-Samper, Elisa Garrido

Desde nuestras primeras investigaciones sobre la estancia de Alexander von Humboldt en España siempre nos sorprendió la ausencia de una mínima relación posterior del sabio prusiano con la corona española y sus autoridades. Iniciada una nueva investigación, encontramos que efectivamente se produjo el envío de un primer trabajo a Carlos IV desde Roma acompañado de una carta de gratitud por la protección recibida durante su viaje americano y de sumisión a la corona española, que ahora presentamos.

Ever since our first research into Alexander von Humboldt’s stay in Spain, the absence of an ensuing relationship between the wise Prussian and the Spanish Crown and Authorities had always surprised us. On starting new research, we found that indeed he sent his first work to Carlos IV from Rome accompanied by a letter of gratitude for the protection he had received during his American trip and submission to the Spanish Crown, which we now present. This first literary fruit of his voyage, which Alexander von Humboldt alluded to in the letter is the first instalment of his work Plantes Équinoxiales, Recueillies au Mexique, dans l’ile de Cuba, dans les provinces de Caracas, de Cumana etc., published in Paris in 1805.

Seit unseren ersten Forschungen über den Aufenthalt Alexander von Humboldts in Spanien hat uns das Fehlen einer hieran anschließenden Beziehung des preußischen Wissenschaftlers mit der spanischen Krone und ihren Behörden erstaunt. Im Laufe einer erneuten Aufnahme der Forschung, haben wir nun entdeckt, dass Humboldt in der Tat von Rom aus eine erste Arbeit an Karl IV gesandt hatte, zusammen mit einem Schreiben des Dankes (für den während der amerikanischen Reise) erhaltenen Schutz sowie seiner Unterordnung unter die spanische Krone, das wir nun präsentieren. Das erste literarische Ergebnis seiner Reise, auf das Humboldt in diesem Brief verweist, ist der erste Faszikel seines Werkes Plantes Équinoxiales, Recueillies au Mexique, dans l’ile de Cuba, dans les provinces de Caracas, de Cumana etc., das im Jahr 1805 in Paris publiziert wurde.

1 Proyecto de Investigación del Ministerio de Economía y Competitividad de España HAR2013–48065-C2–2-P.

Ever since our first research into Alexander von Humboldt’s stay in Spain, the lack of a subsequent relationship between the wise Prussian and the Spanish Crown and Authorities had always surprised us. The only exception was the negotiation for a Spanish trip in the 1830s, finally unsuccessful, when the Ambassador in Saint Petersburg had the idea of inviting him despite Fernando VII’s being on the throne1. Now, on starting new research, we found that indeed he sent his first work to Carlos IV from Rome accompanied by a letter of gratitude and submission to the Spanish Crown. Before going into the content of this document we will briefly comment his stay in Rome after returning from his American voyage.

Between April and October 1805, Alexander von Humboldt left Paris to visit his brother Wilhelm who at the time was the Prussian Ambassador to the Vatican, having obtained permission from the King of Prussia in September of the previous year. For more than six months, Alexander von Humboldt travelled around the Italian peninsula from Mont-Cenis to Vesuvius, passing through Turin, Genoa, Milan, Bologna, Como, Florence, and Rome where he spent most of the time. It was not his first time in Italy, having already been there on two previous occasions; first in 1795, on a visit as a mining manager, and again two years later in 1797 after receiving an inheritance from his mother that would allow him to leave his job at the mining service and undertake one of his first independent travels, starting his new life with a short Italian tour2. When he arrived in Paris after his American trip, his purpose had been to focus on publishing his work. In Paris, he had been in contact with the greatest scientists of the time like Antoine Laurent de Jussieu (1748–1836), Pierre-Simon Laplace (1749–1827), Georges Cuvier (1769–1832), Jean-Baptiste Joseph Delambre (1749–1822), and so on, and had presented some of his scientific discoveries at the Institut de France, where he had been a foreign correspondent member since February 1804. While working together with his publishers, Schoell in Paris and Cotta in Tübingen, his publications were gradually becoming more specific, and at the same time he collaborated with the best scientists from Paris to perfect his texts. Humboldt wanted the best illustrators for one of the most important parts, the engravings that would visually complete his work, so he decided to return to Italy, the great cradle of art, in search of painters and engravers. The Humboldtian mentality3 included the combination of accurate measurements of rational empiricism and aesthetic subjectivity.

The visual production of Humboldt’s work, had three major European capitals: Paris, Berlin and Rome. He lived in the first for a long time working in the edition of his publications of; the second, his birthplace, was a place he always stayed in touch with; and lastly, Rome, which was not only the Arts Capital and an obligatory stage for all those intellectuals who decided to undertake their Grand Tour, but which was also the great German artistic reference place4. There Humboldt made contact with different painters, many of Germanic origin, such as Wilhelm Friedrich Gmelin, Joseph Anton Koch, Johan Christian Reinhart, Gottlieb Schick, and so on, who he met in the capital5, along with other artists of French and Italian nationality6, some of whom participated in the illustration of Vues des Cordillères.

During his stay in Italy, alongside Gay-Lussac, Humboldt was able to make various observations on the composition of air and land magnetism, as well as finish the German version of the Geography of Plants essay, dedicated to Goethe and dated Rome, July 18057. Also, during the stay in Rome, not only was Humboldt able to benefit from making contact with artists, putting them at the service of science by producing his images, he also employed most of his time in the archives of the Vatican and the Roman museums’ collections. There he had the opportunity to see the world of classical antiquity first-hand from the antiquarian Georg Zoëga and to access a multitude of manuscripts and codices that, alongside those of Vienna, Veletri and Berlin, were supposed to be the main source of his hieroglyphic engravings in Vues des Cordillères:

J’avais fait beaucoup dessiner ici. Il y a des peintres qui de mes plus petites esquisses font des tableaux. On a dessiné le Rio de Vinagre8, le pont d’Icononzo9, le Cayambé10 etc. J’ai aussi trouvé chez Borgia un trésor, un manuscrit mexicain dont je publierai plusieurs planches11. J’en ai déjà fait graver ici.12

Since returning from the American voyage the Humboldt brothers had not seen each other, the visit of Humboldt was of much interest to his brother. Wilhelm obtained the documentation on Amerindian languages and the encounter served as a chance for them to be reunited as well as an opportunity to relate his experiences to society. Wilhelm had lived there since 1802 and was a key figure in the scholarly circles of life in the Italian capital, maintaining one of Rome’s most important meeting rooms at his Tommati Palace residence. Alexander was introduced by his brother into the Italian atmosphere of art and culture in all its fullness. The prolific social life held at the Humboldt’s residence is referred to in Alexander’s Note sur le voyage de Humboldt et Gay-Lussac:

La maison de mon frère, alors ministre à Rome, était d’autant plus animée qu’à cette époque Madame de Staël faisait les délices de la ville éternelle, que les grands artistes Thorwaldsen et Rauch fréquentaient journellement la maison, que Léopold von Buch s’y trouvait.13

His brother Wilhelm’s House, in Rome, had become a strategic meeting place for a large section of the foreign intellectuals visiting the country. Among them was Madame de Staël (1766–1817), a key figure who exerted great influence on Parisian cultural life thanks to her meeting rooms where intellectuals, artists, politicians and renowned nobles of the time gathered. It seems that the same spirit reigned in Wilhelm von Humboldt’s house, where he received a visit from her during her stay in the capital when she met Alexander von Humboldt who had recently arrived from his transatlantic voyage14, as well as from several scientists and artists such as Bertel Thorwaldsen (1770–1844), Christian Daniel Rauch (1777–1857), and Christian Leopold von Buch (1774–1853).

Although this episode in Humboldt’s life is generally well-known, it has not received excessive attention by his biographers who have devoted themselves mainly to the American voyage15. But as Marie-Noëlle Bourguet has argued, Rome became to Humboldt the universal city par excellence which offered, in its museums, libraries and monuments; the material he needed to understand both the physical history of the Earth and the art and civilization of different peoples of the world16.

The letter sent by Alexander von Humboldt to King Carlos IV of Spain was delivered via Antonio de Vargas y Laguna (1763–1823), the Chargé d’affaires in Rome who then would refer it on to the Secretary of State Pedro Cevallos Guerra (1759–1839) on September 15, 1805 before being passed on to King Carlos IV. The same day Minister Cevallos answered in Italian from the Palazzo di Spagna to the Baron “Alessandro d’Humbolt” (sic), that the letter would immediately be sent to Madrid and the work submitted to the King, as well as another letter and statement sent to Manuel de Godoy (1767–1851), the Prince de la Paz. Just a month later, he sent a communication to Antonio de Vargas from the Royals thanking Humboldt for shipping them this scientific report, the result of his five-year trip around the Spanish Crown’s American domains, expressing their appreciation for the “vast knowledge” and “moral qualities” of the Prussian scholar, which was given to Humboldt by the Spanish Embassy17.

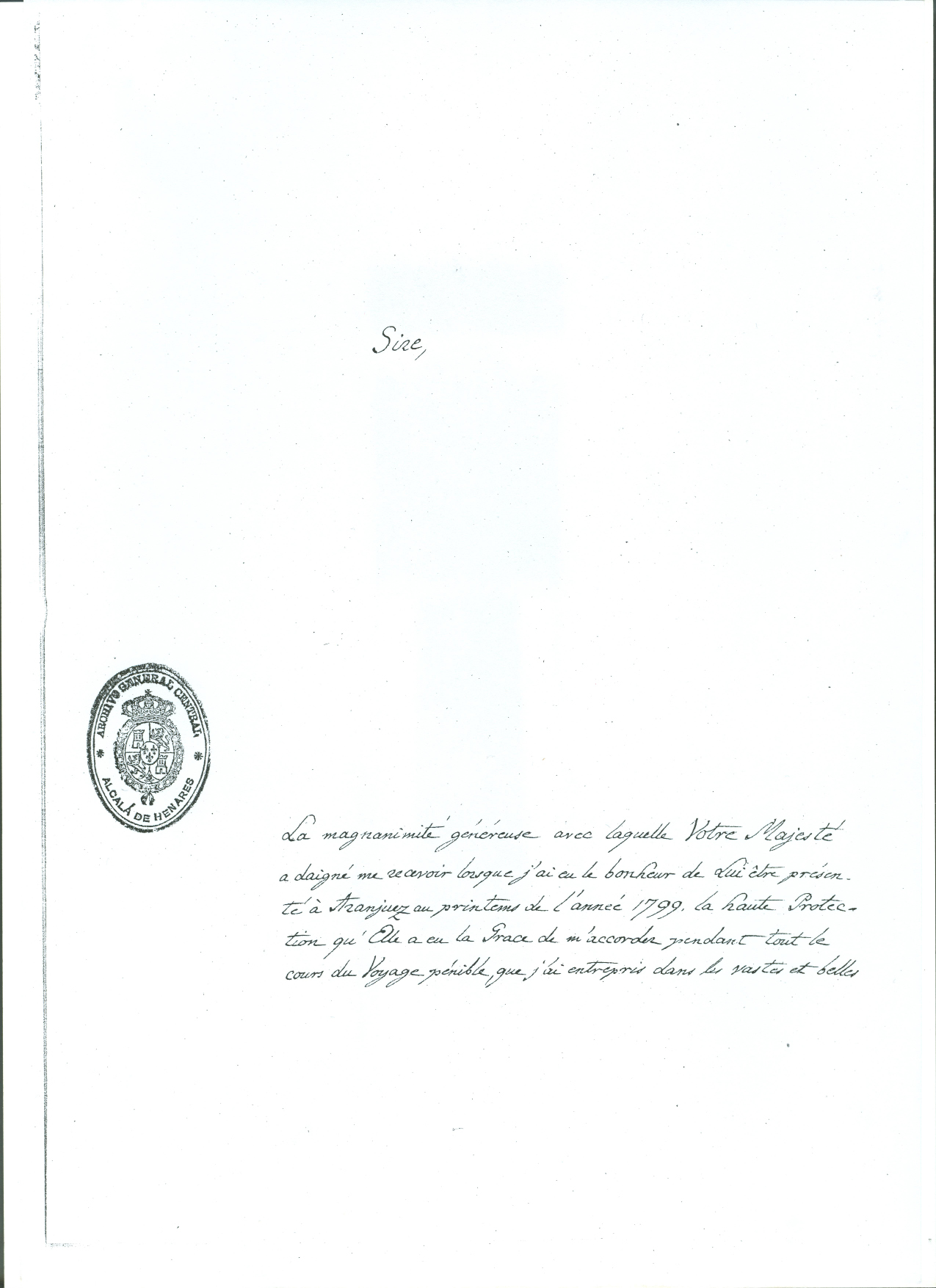

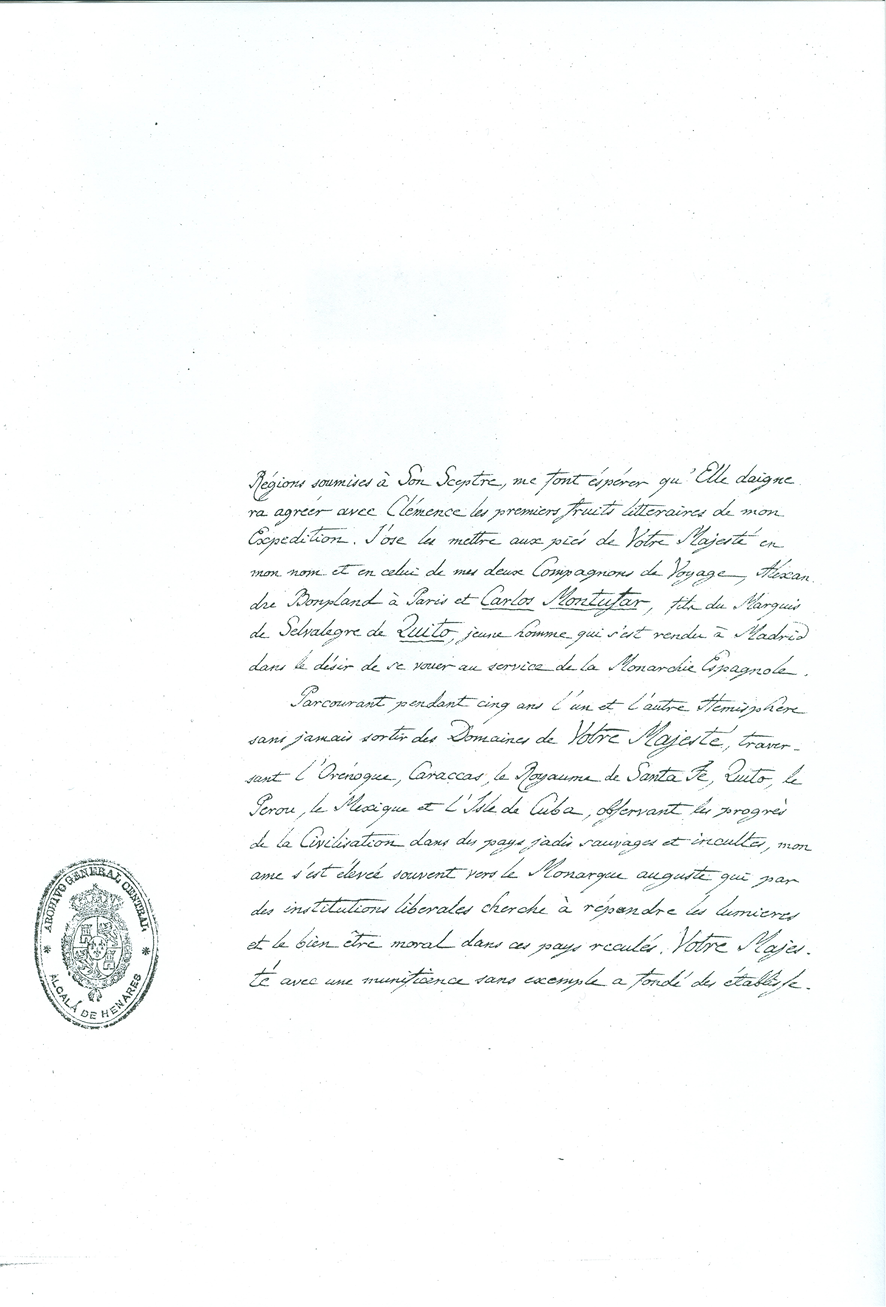

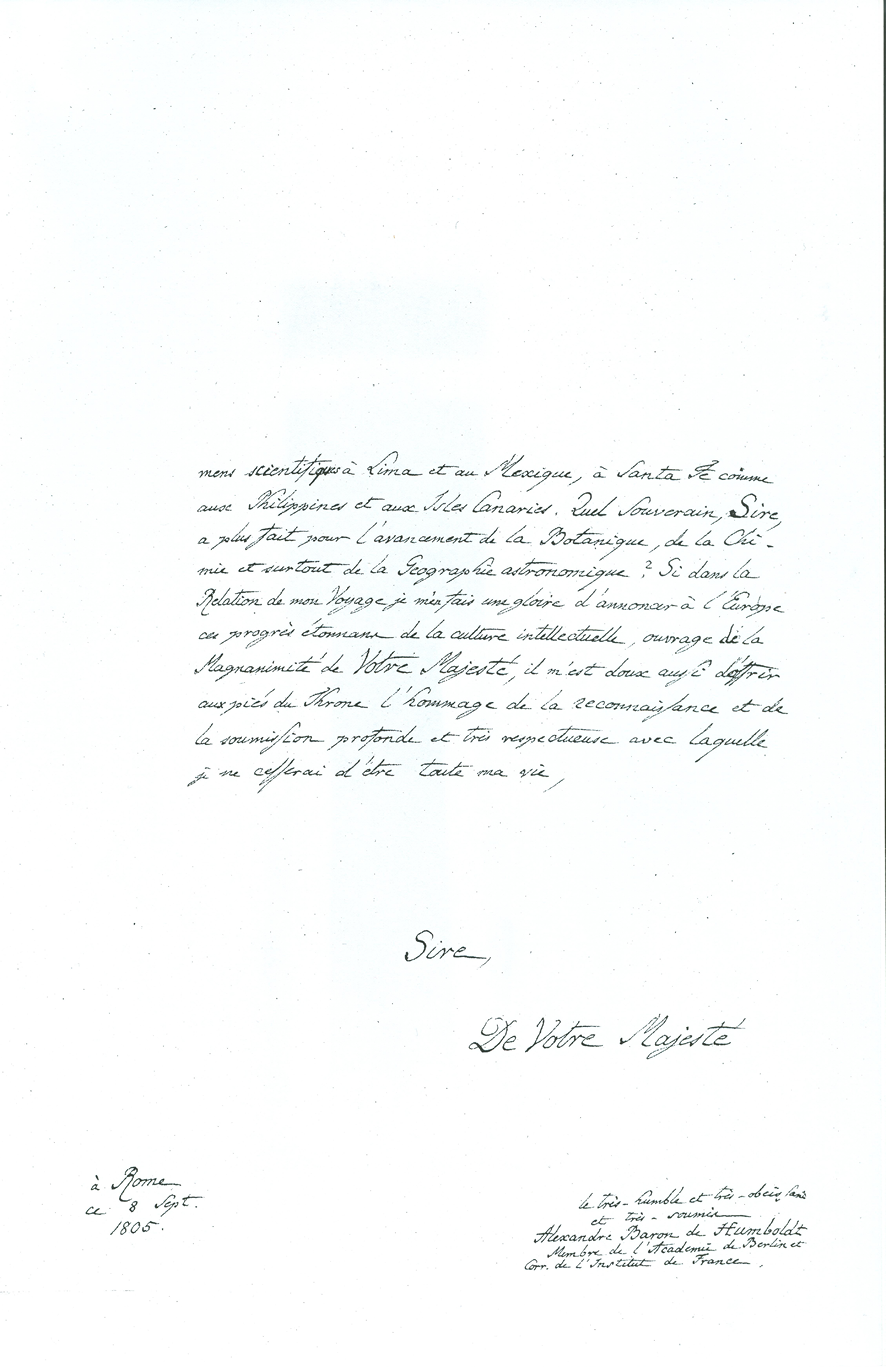

Humboldt’s letter to the King reads as follows:

Sire, La magnanimité généreuse avec laquelle Votre Majesté a daigné me recevoir lorsque j’ai eu le bonheur de Lui être présenté à Aranjuez au printems de l’année 1799. La haute Protection qu’Elle a eu la Grace de m’accorder pendant tout le cours du Voyage pénible, que j’ai entrepris dans les vastes et belles Régions soumises à Son Sceptre, me font espérer qu’Elle daignera agréer avec Clémence les premiers fruits littéraires de mon Expédition. J’ose les mettre aux piés de Votre Majesté en mon nom et en celui de mes deux Compagnons de Voyage, Alexandre Bonpland à Paris et Carlos Montúfar, fils du Marquis de Selvalegre de Quito, jeune homme qui s’est rendu à Madrid dans le désir de se vouer au service de la Monarchie Espagnole. Parcourant pendant cinq ans l’un et l’autre Hémisphère sans jamais sortir des Domaines de Votre Majesté, traversant l’Orénoque, Caraccas, le Royaume de Santa Fe, Quito, le Pérou, le Mexique et l’Isle de Cuba, observant les progrès de la Civilisation dans des pays jadis sauvages et incultes, mon ame s’est élevée souvent vers le Monarque Auguste qui par des institutions liberales cherche à répandre les lumières et le bien être moral dans ces pays reculés. Votre Majesté avec une munificence sans exemple a fondé des établissemens scientifiques à Lima et au Mexique, à Santa Fe comme aux Philippines et aux Isles Canaries. Quel Souverain, Sire, a plus fait pour l’avancement de la Botanique, de la Chimie et surtout de la Geographie astronomique? Si dans la Relation de mon Voyage je m’en fais une gloire d’annoncer à l’Europe ces progrès étonnans de la culture intellectuelle, ouvrage de la Magnanimité de Votre Majesté, il m’est doux aussi d’offrir aux piés du Throne l’hommage de la reconnaissance et de la soumission profonde et très respectueuse avec laquelle je ne cesserai d’etre toute ma vie,

Sire,

De Votre Majesté

à Rome le très-humble et très-obéissant

ce 8 Sept. et très-soumis

1805. Alexandre Baron de Humboldt Membre de l’Academie de Berlin et Corr. de l’Institut de France.

(Archivo Histórico Nacional de España, Estado, leg. 5749)

Carta Humboldt a Carlos IV 1805, Archivo Histórico Nacional de España, Estado, leg. 5749

Carta Humboldt a Carlos IV 1805, Archivo Histórico Nacional de España, Estado, leg. 5749

Carta Humboldt a Carlos IV 1805, Archivo Histórico Nacional de España, Estado, leg. 5749

This first literary fruit of his voyage which Alexander von Humboldt alluded to in the letter is undoubtedly the first instalment of his work Plantes Équinoxiales, Recueillies au Mexique, dans l’ile de Cuba, dans les provinces de Caracas, de Cumana et de Barcelonne, aux Andes de la Nouvelle-Grenade, de Quito et du Pérou, et sur les bords du Rio-Negro, de l’Orénoque et de la rivière des Amazones, published in Paris in 1805 by Levrault, Schoell et comp., can be found in the Royal Palace of Madrid library with a handwritten dedication devoted to the King’s own Alexandre de Humboldt, Alexandre (sic) Bonpland and Carlos Montúfar signed in Rome on the same date as the letter. This instalment contained a preface signed by Humboldt, the description of the Ceroxylon genus and a report on palm wax, accompanied by two drawings by Turpin and engraved by Sellier and read by Bonpland in the Institut de France.

It is interesting that the dedication to the Spanish King includes not only Bonpland’s name but also Carlos Montúfar’s. This character, who not much is known about, accompanied the two travellers during most of their American voyage. The fact that Baron von Humboldt financed the whole exhibition’s cost from his own pocket, allowed him to decide, almost individually, the route, the technological instruments and, obviously, his companions. Among them, only Bonpland was a permanent companion, but there were other temporary companions such as Carlos Montúfar y Larrea (1780–1816) a Creole from Quito, about whom the only thing we know is what is alluded to in the correspondence of José de Caldas (1768–1816). Humboldt and Bonpland spent six months of their American voyage in Quito, staying in the House of the noble Montúfar family and their departure in June 1802, produced great dismay and sadness among the contacts they made there. Many wanted to follow them on their voyage, including José de Caldas–, a renowned scientist whose work in the Botany and Astronomy field was very prominent at the end of the Eighteenth Century. Caldas was not chosen, however, to follow the expedition but that luck fell to the young Montúfar, a character who was described by Caldas as an “adonis, ignorant, without principles and a spendthrift”18. In a letter addressed to José Celestino Mutis, Caldas scorned the choice of this young man who, apparently, had no scientific training. However, his presence is noted on most of the trip and the truth is that the man from Quito accompanied the illustrious members of the expedition for more than two years in their subsequent travels to Guayaquil and Acapulco, Mexico, Havana and during their visit to the United States, where they met Thomas Jefferson, and who later shared the glory of their celebrated return to Paris with Humboldt and Bonpland. In 1805 he moved to Madrid, recommended by Humboldt, to complete his military training at the Academia de Nobles. He remained in Spain for several years and from 1808 he was committed to the war against the Napoleonic invasion. We know that he became Lieutenant-Colonel of the Royal armies in Spain and finally in 1810 he returned to Quito to form a provincial government loyal to the Bourbons. However, as he became aware of the riots occurring in favour of American independence, he eventually changed sides and became an ardent supporter of emancipation, fighting against the Spanish on several battle-fields.

Humboldt’s preface certainly contained the literary message he wanted to send to both the scientific community and to the King of Spain. For Humboldt and Bonpland, the dedication to Botany had been the fundamental point of their lengthy trip across American lands, which had put them at risk on many occasions but had also given them much satisfaction. Humboldt expressly recognized Bonpland’s effort and dedication to Botany, although at the end of his Preface he especially noted his own Essay on Plant Geography, which had just been published. According to Humboldt, who considered himself to be a scientist in voluntary isolation, in the solitude of the forest and cut off from the charms of social life, he would not have been able to endure it, were it not for each step presenting him with a wonderful and varied picture of plant forms. It is interesting how in this account Humboldt thanked his predecessors for their scientific work, while at the same time, raising his own work above theirs so there is no doubt about how important his publications were. Therefore, the work of the Swedish botanist Pehr Löfling (1729–1856), who died victim of his scientific curiosity, was interesting, even though he had only come as far as the Orinoco, as much as the illustrious Joseph Franz Freiherr von Jacquin (1766–1839) had only been able to reach the Venezuelan and Cartagenan coasts, while they had penetrated the interior of South America, from the Caracas coast to the Brazilian border, noting their research in New Andalucía, the Cumanacoa valleys, Guyana, the Orinoco, the Casiquiare, the Río Negro, the Atures and Maypures falls and so on, that always followed the model of the aforementioned famous famous botanists.

Still showing great respect for José Celestino Mutis, who he dedicated this work to and deserved eternal gratitude, Humboldt stated that although this wise man from Cadiz had explored the forests of Turbaco, the beautiful banks of the Magdalena river and the surroundings of Mariquita, he had not been able to penetrate the Quindiu Andes in the Popayán and Pasto provinces, where he and Bonpland had made wonderful botanical discoveries. Something similar happened with Joseph de Jussieu, a scholar whose work was largely lost to European science, while the work done by Humboldt in Quito and Peru was very important. So much that, although Hipólito Ruiz and José Pavón had revealed many Peruvian plants, they were unaware of many of the yields east of the Cordillera de los Andes. Likewise, still acknowledging the merit of Vicente Cervantes, Martín de Sessé and José Mariano Mociño, Member of the Royal Botanical expedition to New Spain, Humboldt boasted of possessing exemplary Mexican vegetables that had escaped the “wisdom” of these botanists, especially if we considered that Humboldt and Bonpland’s collection totalled 6,200 plant species, divided into three collections. Knowing without a doubt the valuable Spanish botanists’ work, in the Preface Humboldt exonerated the possible anticipation that he could be nominated for many new species, which would allow him the priority in the discovery, which was essential in this competitive world of science:

Nous possédons sans doute beaucoup de plantes qui se trouvent dans les herbiers de nos amis, MM. Mutis, Ruiz, Pavon, Cervantes, Mociño y Sessé: ayant herborisé dans des pays qui jouissent d’un climat analogue, il est naturel que nous ayons rencontré les mêmes végétaux. Ce sera pour nous un devoir bien doux á remplir que d’indiquer ce que nous devons á ces botanistes célèbres; mais ce ne sera pas notre faute si, quelquefois, ignorant leurs travaux, nous donnons de nouveaux noms á des genres auxquels ils peuvent en avoir destiné d’autres long-temps avant nous.19

It seemed that this topic haunted him at some moments of his life, and in a letter, written in Rome on June 10, 1805, addressed to Aimé Bonpland he recalled the need to explicitly recognize the scientific work of some Spanish scholars such as Luis Née, in his case Spanish-French, Francisco Antonio Zea, Antonio José Cavanilles, Martín de Sessé, José Pavón, Hipolito Ruiz, Juan José Tafalla or Vicente Olmedo20. A special case was no doubt José Celestino Mutis, he placed his portrait at the front of his botanical work with a dedication that said: “To Don José Celestino Mutis, Director in Chief of the Botanical Expedition to the Kingdom of New Granada, Royal Astronomer in Santa-Fe of Bogota, as a little sign of my admiration and recognition. Alexandre de Humboldt, Aimé Bonpland.” It didn’t seem that the Spanish botanists fully accepted the recognition, if we consider Mariano Lagasca’s claim shortly afterwards that Humboldt granted scant credit to Mutis’ work, especially in relation to iconographic heritage, since he considered that some drawings from Humboldt and Bonpland’s work were copies of the Flora of Bogotá21, although it is also true that, as he himself affirmed, he was unaware that the biography that Humboldt had dedicated to José Celestino Mutis in Michaud’s biographical encyclopedia, had plenty of praise and recognition for the wise man from Cadiz22.

It was not the first time that he appeared to praise to the royal Spanish Crown’s support and so we must remember that in the account presented to President Jefferson and later published in the United States, Humboldt expressly thanked this circumstance:

Una serie de circunstancias favorables le hicieron obtener en febrero de 1799 de la Corte de Madrid un permiso para pasar a las colonias españolas de las dos Américas, un permiso expedido con una liberalidad y franqueza que honraba al gobierno y al Siglo Filosófico. Después de una estancia de algunos meses en la Corte de Madrid, donde el Rey mostró un interés personal por esta expedición, Humboldt salió en junio de 1799 de Europa, acompañado por su amigo el ciudadano Bonpland, que añadía a sus profundos conocimientos en botánica y en zoología un celo incansable. Fue con este amigo con el que Humboldt realizó durante cinco años y a sus propias expensas un viaje por los dos hemisferios, un viaje por tierra y por mar, que ha sido el más grande que jamás se ha llevado a cabo por un particular.23

An acknowledgement that is repeated in his friend J.-Claude Delamétherie’s (1743–1817) account, who no doubt Humboldt had given all sorts of details, in the Notice d’un voyage aux tropiques exécuté por MM. Humboldt et Bonpland en 1799, 1800, 1801, 1802, 1803 et 1804, published in the Journal de Physique, de Chimie et d’Histoire Naturelle, where Carlos IV’s personal interests in the success of Humboldt and Bonpland’s American expedition was noted, organized in order to do any research that would be useful for the progress of science, as well as for the service of Spain or for the recognition of some Spanish scientists, such as Löfling, Mutis, Jorge Juan, Antonio de Ulloa, Montúfar, Espinosa, Alcalá Galiano, Cervantes, Sessé, Fausto de Elhúyar, Ferrer and Andrés Manuel del Río 24.

It would not be the last time that Humboldt showed to King Carlos IV his gratitude and praise his patronage of science in his colonial dominions, as in the dedication of Ensayo político sobre el Reino de Nueva España in 1808, something that may seem contradictory to his sympathies towards the American emancipation movement and which was deleted from many editions of this work25. It was not understood that the wise revolutionary, at the same time as being a ‘coquetease’ to a King who reigned over a decaying Empire, praised the American emancipation movement, but it is clear that this was part of Alexander von Humboldt’s personality, he ended his days as the King of Prussia’s courtier. Humboldt laughed at his critics, who had even suggested that his submission to the King of Spain was due to the fact that he had been offered a seat on the Council of the Indies. As he wrote to his teacher and friend Carl Ludwig Willdenow mocking this possibility for a man of action like him and stressing that his voyage was independent of any Government, despite being very grateful to the Spanish Government and especially Minister Urquijo26.

Blennerhassett, Charlotte (2013): Madame de Staël: Her Friends, and Her Influence in Politics and Literature. Vol. 3. New York: Cambridge University Press.

Bourguet, Marie-Noëlle (2004): Écriture du voyage et construction savante du monde: le carnet d’Italie d’Alexander von Humboldt. Preprint 266. Berlin: Max-Planck-Inst. für Wissenschaftsgeschichte.

Delamétherie, J.-C. (1804) : “Notice d’un voyage aux tropiques exécuté por MM. Humboldt et Bonpland en 1799, 1800, 1801, 1802, 1803 et 1804”, Journal de Physique, de Chimie et d’Histoire Naturelle, Tome LIX, Paris: J.J. Fuchs, pp. 122–139.

Dettelbach, Michael (1999): “The Face of Nature: Precise Measurement, Mapping, and Sensibility in the Work of Alexander von Humboldt”, Stud. Hist. Phil.Biol. & Biomed. Sci., Vol. 30, nº 4, pp. 473–504.

González, Beatriz (2001): “La escuela de paisaje de Humboldt“. In: Holl, Frank (Ed.): El regreso de Humboldt. Quito: Imprenta Mariscal, pp. 87–90.

Hampe, Teodoro (2002): “Carlos Montúfar y Larrea (1780–1826), el quiteño compañero de Humboldt”, Revista de Indias, Vol. 62, nº 226, Madrid, pp. 711–720.

Hamy, Ernest-Théodore (1905): Lettres américaines d’Alexandre de Humboldt (1798–1807). Paris: E. Guilmoto.

Hossard, Nicolas (2004) (Ed.): Alexander von Humboldt & Aimé Bonpland. Correspondance 1805–1858. Paris, Budapest, Torino: L’Harmattan.

Humboldt, Alexandre de y Bonpland, Aimé (1805): Plantes Équinoxiales, Recueillies au Mexique, dans l’ile de Cuba, dans les provinces de Caracas, de Cumana et de Barcelonne, aux Andes de la Nouvelle-Grenade, de Quito et du Pérou, et sur les bords du Rio-Negro, de l’Orénoque et de la rivière des Amazones. Paris: Chez Levrault, Schoell et Comp.

Humboldt, Alexander von (1816): Vues des cordillères, et monumens des peuples indigènes de l’Amérique. Paris: Schoell.

Moheit, Ulrike (1993) (Ed.): Alexander von Humboldt. Briefe aus Amerika 1799–1804. Berlin: Akademie Verlag (Beiträge zur Alexander-von-Humboldt-Forschung, 16).

Puig-Samper, Miguel Ángel (1999): “Alejandro de Humboldt, un prusiano en la corte de Carlos IV”, Revista de Indias, Vol. 59, nº 216, Madrid, pp. 329–355.

Puig-Samper, Miguel Ángel, J. Luis Maldonado Polo y Xosé Fraga (2004): “Dos cartas inéditas de Lagasca a Humboldt en torno al legado de Mutis”, Asclepio, Vol. LVI-2, pp. 65–86.

Puig-Samper, Miguel Ángel y Sandra Rebok (2002): “Alexander von Humboldt y el relato de su viaje americano redactado en Filadelfia”, Revista de Indias, Vol. 62, nº 224, pp. 209–223.

Puig-Samper, Miguel Ángel y Rebok, Sandra (2007): Sentir y medir. Alexander von Humboldt en España. Madrid: Doce Calles.

Rieck, Hans (1977): „Alexander von Humboldts Reise durch Italien (1805)“, Petermanns Geographische Mitteilungen, nº 121, pp. 23–26.

1 Puig-Samper, Miguel Ángel (1999): “Alejandro de Humboldt, un prusiano en la corte de Carlos IV”, Revista de Indias, Vol. 59, nº 216, Madrid, pp. 329–355.

2 Bourguet, Marie-Noëlle (2004): Écriture du voyage et construction savante du monde: le carnet d’Italie d’Alexander von Humboldt. Preprint 266. Berlin: Max-Planck-Inst. für Wissenschaftsgeschichte, p. 3.

3 The search of the scientific objectivity without the observer leaving the aesthetic subjectivity appeared from the start of his trip, during his stay in Spain. See Puig-Samper, Miguel Ángel and Sandra Rebok (2007): Sentir y medir. Alexander von Humboldt en España. Madrid: Doce Calles; Dettelbach, Michael (1999): “The Face of Nature: Precise Measurement, Mapping, and Sensibility in the Work of Alexander von Humboldt”, Stud. Hist. Phil.Biol. & Biomed. Sci.,Vol. 30, nº 4, pp. 473–504.

4 German classicism was booming after the success of Winckelmann’s work Art History in Antiquity (1764), which followed the publication of Goethe’s Trip to Italy, whose narration of his stay on the Italian peninsular between 1786 and 1788 marked a new form of aesthetically relating the voyage.

5 González, Beatriz (2001): “La escuela de paisaje de Humboldt”. In: Holl, Frank (Ed.): El regreso de Humboldt. Quito: Imprenta Mariscal, pp. 87–90.

6 “L’Atlas pittoresque qui accompagne l’édition in – 4º du Voyage de MM. de Humboldt et Bonpland dans les régions équinoxiales du nouveau continent, forme un volume grand in-folio, orné de soixante-neuf planches exécutées par les premiers artistes de Paris, de Rome et de Berlin”. Cfr. Alexander von (1816): Vues des cordillères, et monumens des peuples indigènes de l’Amérique. París: Schoell.

7 Bourguet, Marie-Noëlle (2004): Écriture du voyage et construction savante du monde: le carnet d’Italie d’Alexander von Humboldt. Preprint 266. Max-Planck-Inst. für Wissenschaftsgeschichte, pp. 11 and 43–44.

8 “Cascade du Río de Vinagre”, lám. XXX de Vues des Cordillères. Drawing by Koch in Roma, according a sketch of Humboldt; Engraved by Arnold in Berlín.

9 “Ponts naturels de l’Icononzo”, lám. IV de Vues des Cordillères; Drawing according a sketch of Humboldt; Engraved by Gmelin in Roma.

10 “Volcán de Cajambé”, lám. XLII de Vues des Cordillères. Drawing by Marchais according a sketch of Humboldt; Engraved by Bouquet.

11 The Borgia Codex. The Vatican manuscripts served Humboldt to illustrate many of his engravings: láms. XIII, XIV, XXVI y LX de Vues des Cordillères, pp. 56–89; 202–211.

12 Humboldt à Bonpland; Rome, le 10 Juin 1805, in Hamy, Ernest-Théodore (1905): Lettres américaines d’Alexandre de Humboldt (1798–1807) précédées d’une notice de J.-C. Delamétherie et suivies d’un choix de documents en partie inédits. Paris: E. Guilmoto, p. 191. A better source for this quotation is: Hossard, Nicolas (2004) (Ed.): Alexander von Humboldt & Aimé Bonpland. Correspondance 1805–1858. Paris, Budapest, Torino: L’Harmattan, p. 16.

13 Hamy, Ernest-Théodore (1905): Lettres américaines d’Alexandre de Humboldt (1798–1807). Paris: E. Guilmoto, pp. 244- 247.

14 Blennerhassett, Charlotte (2013): Madame de Staël: Her Friends, and Her Influence in Politics and Literature. Vol. 3. New York: Cambridge University Press, p. 134.

15 Rieck, Hans (1997): „Alexander von Humboldts Reise durch Italien (1805)“, Petermanns Geographische Mitteilungen, nº 121, pp. 23–26.

16 Bourguet 2004, p. 65.

17 Archivo Histórico Nacional de España (AHN), Estado, leg. 5749 and Archivo General del Ministerio de Asuntos Exteriores y de Cooperación (AMAE), leg. 730.

18 Hampe, Teodoro (2002): “Carlos Montúfar y Larrea (1780–1826), el quiteño compañero de Humboldt”, Revista de Indias, Vol. 62, nº 226, Madrid, pp. 711–720.

19 Humboldt, Alexandre de et Bonpland, Aimé (1805): Plantes Équinoxiales, Recueillies au Mexique, dans l’ile de Cuba, dans les provinces de Caracas, de Cumana et de Barcelonne, aux Andes de la Nouvelle-Grenade, de Quito et du Pérou, et sur les bords du Rio-Negro, de l’Orénoque et de la rivière des Amazones, Paris: Chez Levrault, Schoell et Comp., p. V.

20 Humboldt à Aimé Bonpland. Rome, 10 juin 1805. In: Hamy 1905, pp. 190–191. Hossard 2004, pp. 14–15.

21 Puig-Samper, Miguel Ángel, J. Luis Maldonado Polo and Xosé Fraga (2004): “Dos cartas inéditas de Lagasca a Humboldt en torno al legado de Mutis”, Asclepio, Vol. LVI-2, pp. 65–86.

22 Biographie Universelle ancienne et moderne. Publiée sous la direction de Michaud, M., Paris: C. Desplaces Éditeur, 29, 1843, pp. 658–662.

23 Puig-Samper, Miguel Ángel and Sandra Rebok (2002): “Alexander von Humboldt y el relato de su viaje americano redactado en Filadelfia”, Revista de Indias, Vol. 62, nº 224, Madrid, pp. 75, 209–223.

24 J.-C. Delamétherie (1804): “Notice d’un voyage aux tropiques exécuté por MM. Humboldt et Bonpland en 1799, 1800, 1801, 1802, 1803 et 1804”, Journal de Physique, de Chimie et d’Histoire Naturelle, Tome LIX, Paris: J.J. Fuchs, pp. 122–139.

25 “A su majestad católica Carlos IV, Rey de España y de las Indias. Señor, Habiendo disfrutado, durante muchos años, en las lejanas regiones sometidas al Cetro de Vuestra Majestad, de su protección y de su alta benevolencia, yo no hago más que cumplir un deber sagrado al depositar al pie de Su Trono el homenaje de mi reconocimiento profundo y respetuoso. En 1799, en Aranjuez, tuve la dicha de ser recibido personalmente por Vuestra Majestad, la que se dignó aplaudir el celo de un sencillo particular al que el amor a las ciencias llevaba hacia las riveras del Orinoco y la cima de los Andes. Por la confianza que los favores de Vuestra Majestad me han inspirado, es por lo que me atrevo a colocar su nombre augusto al frente de esta obra, que traza el cuadro de un vasto reino, cuya prosperidad, Señor, es grata a vuestro corazón. Ninguno de los monarcas que han ocupado el Trono Castellano ha difundido más liberalmente que Vuestra Majestad los conocimientos precisos sobre el estado de esta bella porción del globo, que, en ambos hemisferios, obedece a las leyes españolas. Las costas de América han sido levantadas por hábiles astrónomos, con munificencia digna de un gran soberano. Han sido publicadas a expensas de Vuestra Majestad cartas exactas de las mismas costas y también planos detallados de varios puertos militares. Ha ordenado Vuestra Majestad que anualmente, en Lima, en un periódico peruano, se publiquen datos estadísticos sobre los progresos de la población, del comercio y de las finanzas. Faltaba aún un ensayo estadístico sobre el reino de la Nueva España. He reunido un gran número de materiales de mi propiedad en una obra cuyo primer bosquejo Había llamado honorablemente la atención del virrey de México en 1804. Sería feliz si pudiera lisonjearme de que mi humilde trabajo, en forma nueva y redactado con más atención, no fuera indigno de ser presentado a Vuestra Majestad. Mi obra refleja los sentimientos de gratitud que debo al Gobierno que me ha protegido y a esta Nación, noble y leal, que me ha recibido no como a un viajero, sino como un conciudadano. ¿Cómo podría desagradar a un buen Rey, cuando el mismo se refiere al interés nacional, al perfeccionamiento de las instituciones sociales y a los principios eternos sobre los cuales reposa la prosperidad de los pueblos? Soy, con todo respeto, Señor, el más humilde y sumiso servidor de Vuestra Majestad Católica. París, 8 de marzo de 1808. El Barón de Humboldt.”

26 Humboldt to Willdenow. La Havana, 21. February 1801. In: Hamy (1905), p. 113. A better source for this quotation is: Moheit, Ulrike (1993) (Ed.): Alexander von Humboldt. Briefe aus Amerika 1799–1804. Berlin: Akademie Verlag, p. 126 (Beiträge zur Alexander-von-Humboldt-Forschung, 16).